Strategies

A Multiple Intelligences Lesson

Branching out: A Multiple Intelligences Lesson

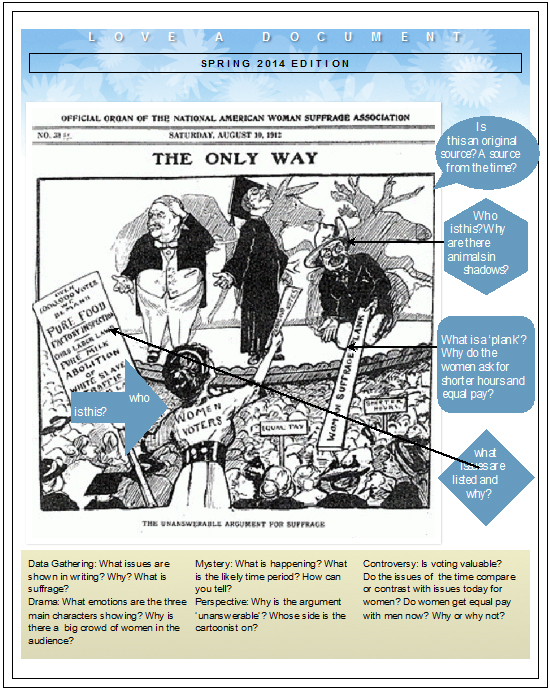

Love a Document/Creating your own primary source analysis

Ask participants which intelligences ‘Love a Document’ calls for from pupils. Use the example below. Also choose a primary source of your own and develop it in the same way, or better.

Direct participants to research, scrutinize, and prepare their own ‘Love a Document’ lesson (media, word, or picture) that they view as having historical significance.

Make sure your own new questions are attached to the document.

Direct observations to picture details using ‘balloons,’ ‘pointers,’ ‘laser beams,’ and the like to call attention to significant clues to understanding.

Suggest that word or page templates be used to create user-friendly newsletters, journals, advertisements, diaries, or other common forms to present and analyze historical/social science sources.

Perhaps you might e-mail or text a document for all to develop on iPhones or iPads. Share answers and interpretations immediately!

“The Only Way” (Cartoon, August 18, 1912)

Heroes and Villains in History

Branching out: Wild Social Studies

Choose two persons, one in American history and one in world history, whom you think are worthy of being considered ‘heroes’ or ‘villains.’ Try not to pick people beyond question, like George Washington or Adolf Hitler. Choose people who are ‘discussible’ and interesting but who may be evaluated from multiple perspectives. Write a short rationale for your choice and look up at least three historians’ views about your person. For example, President Harry Truman or Emma Goldman would be interesting choices because both did things that can be praised and condemned, or at least debated from a number of viewpoints.

Unit Creation from Start to Finish Two Big Examples

Introduction

Unit Creation from Start to Finish: Two Big Examples

New Age of Multimedia: Creating a New Unit from Start to Finish on Heroines/Heroes and Villains in History

(Coordinated with Chapter 7: “Creating a New Unit from Start to Finish on the Glories of Ancient Greece, American Democracy, and More: Meeting and Exceeding the Standards”)

Develop a Unit on “Heroes or Villains” in History

A Sample of Essential Questions about Heroines and Heroes

- Who is a hero/heroine in history?

- Why do people need to believe in heroes/heroines?

- Do believers sometimes lose faith in heroes/heroines? Why?

- Can we live without heroes/heroines?

- What standards, criteria, or rules can we develop to identify heroic actions or heroic people?

- Why do some nations extol certain leaders but forget others? Why do some nations focus on only a few as outstanding? Do countries promote leaders as heroes for special purposes? What might those goals be? Do you agree with these goals as civic education, or do you see them as propaganda?

The Mystery of Heroines and Heroes

It is so very human to want heroes and heroines in our lives to guide us and inspire us, serving as exemplars, as models for our own growth and development in a society.

Yet we are often unconscious of just why we like someone or identify so strongly with them, and we project onto them perhaps qualities that are mythical and unattainable by real human beings. For us, some people symbolize the qualities of leadership, faith, enjoyment, and satisfaction that may escape us in our own lives. We will argue that history is replete with heroes, and to a lesser extent (alas) heroines, who are often written about and described in reverential tones. To them we ascribe great accomplishments, enormous strength and leadership, great warmth and compassion. Pictures, paintings, and sculptures of these people begin to grow into myth and magic, to be used as both propaganda and legends that can live in our minds and influence our decisions. In this chapter, we want to apply several views of heroism and heroics to historical evidence in the form of both biographic information and fantasy figures, using both as tests of our own values and beliefs, and as historical weather vanes to get a feel for the trends of the times.

This rather major mystery will focus partly on why we seem to need heroines and heroes, especially as leaders, and also how the concept is extended to daily life with the possibility of ‘ordinary’ heroines and heroes as well as exalted ones. On the way, we will also investigate many other smaller mysteries about defining terms, idealization, fantasy, and propaganda in states both ancient and modern. We will call upon you to consider questions of leadership, and why we are often willing to believe in the greatness and heroism of a leader who is, after a bad fall, all too human.

Within issues of leadership we think there are quite a few gender problems, since much of heroism appears to be heavily dominated by masculine models and stereotypes, as in war heroes or leaders, with far less available in the way of feminine models and stereotypes. An example might be the way war is treated as a male province, although there are women warriors as well, but is there equal attention or equal identification?

Thus, there may be opportunities to correlate some of the examples in this chapter with the chapter of women in world history, as a way of connecting people in history and better understanding the overall problem of identifying the heroic.

To accomplish this goal, we will provide you with several definitions of hero subject to your modification and revision. Throughout history as we know it and teach it are a host of people that seem to have special rights to attention, space, and glorious images, while others languish in relative or total obscurity. The reason why certain people receive reverent attention and others are rapidly dismissed is one of the mysteries we would like to investigate, a mystery that actually carries a lot of historical baggage. Much depends on your values and the values of historians who tell of the past and present and determine who achieves heroic status. For example, do you really believe that individuals make history, and that solitary heroes or leaders can change things on their own initiatives, or do you think that social forces are always at work shaping us and all the people around us? Thus, within the ‘hero’ concept is a battle of historians and philosophers, political leaders and social movements, artists and writers, image-makers and propagandists, to capture hearts and minds, win offices, make money, and take power.

The way we view a heroine or hero decides who should be accorded that elevated status, and why we should take any of it seriously can and does affect each and every life in the world. Even in the realm of mythology, heroism can be hotly debated, as we have many role models to choose from: Wonder Woman, Batman, The Lady of the Lake, Ivanhoe, King Arthur, gods and goddesses, and so forth. And all raise much the same questions about ‘ordinary heroes’ vs. ‘elite leader heroes,’ as well as the types of action, battle, catastrophe, caring, social movement participation, and so on, that justify awarding the certificate of heroism.

Plan of Action

The existence of heroines and heroes in history, past and present, is a mystery in several ways. We will cover at least three of these ways in this review of the plan of action for the chapter.

First, we can delve into the human need to ‘look up’ to or idolize other people, real and mythical, in ways that help them carry on their own lives.

Second, we can ask why some people have been idealized and celebrated as heroic, while others have been relatively or absolutely neglected.

Third, we can question just who is a heroine or hero, and what actions, character, and values are attributed to or performed by the person we have raised to the level of heroic.

There may be other key, essential, or critical questions we can raise, but we need some solid content to serve as a springboard for investigation, and we need a strategy to provoke student thinking in ways they don’t expect.

Before proceeding to our examples from history, we encourage you to engage students in a definitional conversation about heroines, heroes, and heroism, in which you try to define your terms. We provide several theories to help you with ideas and to confuse you about just what or who a heroic person is, was, or should be in history.

To accomplish our overall strategy and test your definitions of heroism, we are providing you with a sample of case studies or historical excerpts from a wide variety of times and places, each of which raises different problems about just who is, was, or should be heroic in a historical setting, past or present.

Case studies, called ‘profiles’ in this chapter, will focus on a mix of heroines and heroes across the ages and from many different places, so these will fit into a world history course or program. We make no claims for comprehensiveness since this would take over the whole course, unless you are satisfied with a heroines/heroes course, or perhaps a heroes and villains course. If so, please feel free to apply and adapt our concepts and move ahead with world history as an investigation of heroism and villainy, or some such, with a thorough in-depth study of historical and mythical figures who serve as exemplars for us now and in bygone ages.

Strategy

The heroic in history is a very old topic, one perhaps most often associated with leaders—particularly leaders who have built empires, formed new countries, or reshaped old nations. Less often do we think about heroic people in history who have developed from walks of life like sports, medicine, industrial work, religion, or community service, or those who were rebellious and revolutionary. Usually the names we learn in history class are those of conquerors, kings, and presidents, and relatively few women.

Our strategy in this investigation will present a variety of people and movements from across the world, widely separated in time and place. Each tests our sense of heroism and encourages us to examine our own values about who may qualify for the title of ‘heroic’ that we often use quite loosely in casual conversation.

Alexander the Great, King of Macedon and Emperor, has been selected because he is a familiar figure in history—the stuff of legends, as they say—and is regarded by many teachers and students as someone who deserves to be studied as an outstanding leader. A brief biography and some ancient pictures offer a condensed view of his accomplishments and character, by which we intend to kick off the discussion of heroism. To put it bluntly, does conquest entitle someone to be called ‘great’? Do Alexander’s portraits evoke a sense of awe and worship, or ‘hero worship,’ in the past and even today? Is he the real thing, a model hero, or is our image the result of skillful political and visual propaganda?

Next, we will switch gears almost completely and turn to religion for an example, using very ancient and very present material about the Buddhist concept of a bodhisattva, a being who surrenders his or her right to enlightenment, to nirvana, in order to remain on earth in the service of ordinary human beings who need help. Is this kind of selflessness what it takes to give us a sense of heroism? Can a human being seeking and believing in peace and love be heroic, as heroic as Alexander was in warfare, conquest, and organization? Just to make things a bit more complicated, we will offer a very brief biography of the Dalai Lama, spiritual leader of Tibetan Buddhism, as a living example of the concept of the bodhisattva Avalokiteshvara.

Third, we will move back to the realm of politics by comparing two great leaders, George Washington and Napoleon Bonaparte, who both emerged from and helped to lead revolutions, and who both became leaders of their nations. These two historical characters are part of our strategy for honing our definition of heroic, and deciding some important questions posed by history—just what counts as accomplishments for great men.

Do political skills count? Do bravery and warfare count? Do compassion and care count? Do leadership and organization count? Does success count—only success?

After reading an account of Washington’s life and viewing a time line of major events in Napoleon’s life, which figure do you and your students tend to have more sympathy for, and for what reasons? (Remember also that we are looking at limited samples of different kinds of data to draw conclusions. Don’t we need much more information about each gentleman before making a really accurate and comprehensive judgment?)

Fourth, we will take a look at the profiles of four women, all representatives of recent or relatively recent history, but from very different places and environments

Choose women who are somewhat unusual in that they have taken active roles in their communities as leaders, often in opposition to either internal or outside forces arrayed against them and their values. In some cases, women risked their lives for causes they believed in, but which you, our reader, may not necessarily approve of based on your own values. That is fine, but we have to pose the question to you: Is it possible for you to extend the concept of heroism to those with whom you may not necessarily agree?

In any case, four women who might be selected include Wangari Maathai, a Nobel Peace Prize winner from Africa. Beginning in 1977 she led a ‘Green Belt’ movement among women in Kenya, helping them to conserve resources in their towns and villages, and to engage in activities such as replanting trees. Present her story in her own words, crediting her religious upbringing as a motivation to help others less fortunate than herself. Her story may be contrasted with that of Mary Harris “Mother” Jones, an American woman of Irish descent who became one of the most active labor leaders in the United States in her time. At the turn of the 20th century she led strikes and made speeches across the country to improve the lives of working people. She often risked her health and body, and went to jail for her activities, particularly during antilabor periods. She also assisted others, but in ways perhaps quite different from Maathai. And there was no Nobel Prize for Mother Jones!

Jones and Maathai may be further compared with Aung San Suu Kyi, leader of the opposition party in Burma (also called Myanmar), who was held under house arrest from 1989 to 2010. She comes from a family of leaders and has a long record of political activism and nonviolence. But she has greatly angered the regime by her outspokenness and refusal to cooperate with their suppression of freedoms in Burma.

Suu Kyi and others may be compared to a relatively unknown woman nicknamed La Pasionaria, ‘the Passionflower.’ She was a key leader of the Republicans who opposed the fascist Falange movement during the Spanish Civil War of the 1930s. She was a charismatic speaker for revolution and the defense of a free republic for the Spanish people. As a leader of the Spanish Communist Party, she was opposed to the dictatorship offered by General Francisco Franco, who became president after winning the war.

You are invited to compare and contrast these four lives as a guide to deciding which women might be called heroines, and which not, according to the facts of the case and the values you use as criteria for judgment. You are also invited to do a great more research on these women than we have presented. Each is quite interesting on her own terms, and a great deal of information may be available about each one.

Finally, present some ‘hometown’ materials to look over in order to raise the question of ‘ordinary heroes.’ Ask if people from ordinary life can and should play the parts of heroes during wars, catastrophic events, plagues, and other disasters, human or natural, that people have had to face in history. Again we raise questions about who counts as a hero, what types of action ensure the certificate of heroism, and whether one has to risk one’s life in order to be considered heroic. We present profiles, in pictures and words, of a few of the women who worked in heavy industry during World War II. These women, who became known by the nickname ‘Rosie the Riveter,’ were employed to punch rivets into bombers at manufacturing plants during the war. Traditionally, women never worked in heavy industry, and they did the work of men. Were they heroic?

For comparison, and again to test your criteria of heroism, we also present a small set of photos of the firemen who responded to the disaster of September 11, 2001. On that day, the World Trade Center in New York and the Pentagon in Washington, D.C. were hit by hijacked airliners, causing enormous destruction and the deaths of thousands of ordinary citizens and civilians. Were these first responders acting heroically? Do they fit our criteria for heroism even though they did not go into battle, and even though they were not leaders or warriors?

Let us conclude our inquiry by investigating whether organizations can be heroic. As our example we have selected Doctors Without Borders/Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF), a nongovernmental organization founded in France. You and your students will be presented with the MSF’s own statement of mission and service, and will be asked to judge whether it is heroic, and whether those who serve in the organization would be considered latter-day bodhisattvas. We want you to take on the issue of a group, agency, or organization, private or governmental, that will fulfill the qualifications for your standards of heroism. OK?

As a finale, you can move into a wrap-up discussion, using the questions provided at the chapter’s end. You can also give students a last assignment using our supplemental profile on Harriet Tubman, as a case study for comparison with our other heroes/heroines and nonheroes/nonheroines. For those like us, who are obsessed with reviewing history and studying biographies and autobiographies of historical lives, you may want to search the Internet for evidence that will help you refine the concept of hero/heroine. There is plenty of information to choose from on the Internet; some sources are questionable, while others are reliable and accurate. You could even spend a whole year reviewing, judging, and creating heroines and heroes in world history. You could ask all the students to join a ‘Choose a Heroine/Hero’ club, where they identify their top five or ten choices, which may include family, friends, and historical figures—and even pets. Is the title exclusively for humans, or would famous dogs such as Lassie be considered heroes/heroines?

You are encouraged to review many people throughout history, those adored, those disliked, and those in-between; those who were failures and all too human, and those to whom success is ascribed. Please do develop your own set of profiles and cases as a basis for reviewing their qualifications for heroism, and as a means to test the concept of heroine/hero that you and your students have developed in this chapter on world history as mystery.

Defining Hero and Heroine

Don’t forget this early stage of our discussion as a first step in the development of comprehension and criteria for hero and heroine status.

Those we hold in high regard may come from many walks of life: political leaders, entertainers, family and friends; from social movements, religions, myths, and fairy tales. The emotional, social, and political dimensions of heroic people are complex and mysterious. Some of those regarded as heroic may remain so for a long, long time and enter the canons of human history, crossing cultures, times, and places to achieve and retain an aura of greatness—an image of the exemplar to follow. Others may achieve great power and celebrity for a short time, fall from grace, and become labeled as the opposite of heroes: villains.

Investigate and analyze the concept of the heroine/hero to try to determine its component parts, underlying motivations, and psychological underpinnings. Psychology, politics, and anthropology as well as history can aid in this pursuit, giving us an opportunity to play with some fascinating ideas (e.g. the archetypes identified by the Swiss psychiatrist Carl Jung or the more anthropological version of heroics developed by Joseph Campbell).

Take a look at heroes and heroines using the notion of the ‘cult of the personality’ that can arise when a leader is promoted to a larger-than-life status. An important issue embedded in the topic of heroines and heroes is whether we need them or they need us, or both. For example, there are millions of people who love going to films about mythical or cartoon heroes (mostly) and heroines.

Apply evolving definitions and ideas to a series of examples that test our understanding of human behavior in history. Inquire into the reasons for the idealization of certain individuals such that they are lifted to a higher status than most ordinary people. The flip side of heroics, canonization, idealization, and personality cults is the villain, the fallen, the disappointing, and worse yet, the actual human being herself or himself.

In conclusion, heroines and heroes will be presented from many different times and places, from top leaders who are immediately recognizable to everyday folks. Ask your students to dispute the style and moral tone by which historians and literary figures describe those they view as heroic.

Did the heroic figures actually achieve their status through actions they took or didn’t take? Did they gain notoriety from their audience, from the human need to ‘idolize’ and ‘idealize’ mythic and real figures in history to act as our models and guides?

Challenges! Using Mental Maps as Tools of Pre and Post Assessment

Prepare a ‘mental map’ of a unit you wish to use to assess a lesson you have taught. But first, apply a mental map idea to heroes/heroines and villains as a unit.

Use the example below as a guide.

Developing a Mental Map for Deciding Upon a Unit to Teach

- Choose a common topic from the secondary curriculum.

- Apply NCSS C3 standards (and Common Core if you like).

- Draw two or three analogies to your topic, comparing then and now, past and present, on the same subject.

- Invent a few powerful key questions for your topic: didactic, reflective, and affective.

- Set several goals: Match outcomes to didactic, reflective, and affective to goals, and goals to outcomes.

- Define terms and ideas: Offer multiple definitions (e.g. of ‘revolution’).

- List a references and resources database (several popular and scholarly books worth reading and/or websites).

- Provide a rationale: Why are your topic and goals worth doing?

- Choose materials (multiple types).

- Edit, arrange, and review historical, artistic, literary, and media materials to fit your strategy.

- Decide on an overall teaching strategy (compare and contrast, mystery, drama, controversy, etc., suitable to your topic, issues, questions, and materials.

- Invent specific questions for each item in your teaching packet (following Bloom’s taxonomy).

- Decide on outcomes you hope to see students accomplish.

- Give examples/specific details/provide a rubric.

- List criteria for evaluation and judgment, explain how you will make your judgment/grades/quality, etc.

- Collect a bibliography, and annotate the five most important primary sources you read, and three scholarly books on your subject.

Original Quotes on the meaning of Revolution

Examples below on revolution (in the first person planning mode)

I like the topic of revolution in society. It is a powerful idea that cuts across time and space.

I think I will focus on two or three connected/linked by ideas/culturally adapted revolutions, one of which is like another, and one quite different. The American, French, and Mexican Revolutions appeal to me because their ideas are connected, but the American Revolution was so conservative/elitist, while the others were so radical/egalitarian.

A goal: Students will work out their own specific definition of revolution using several examples from the dictionary and from famous people.

- “If I can’t dance to it, it’s not my revolution.”

- ―Emma Goldman

- “The first duty of a man is to think for himself.”

- ―José Martí

- “Better to die fighting for freedom than be a prisoner all the days of your life.”

- ―Bob Marley

- “Poverty is the parent of revolution and crime.”

- ―Aristotle

- “I hold it that a little rebellion now and then is a good thing, and as necessary in the political world as storms in the physical.”

- ―Thomas Jefferson

- “A revolution is not a bed of roses. A revolution is a struggle between the future and the past.”

- ―Fidel Castro

- “The greatest purveyor of violence in the world: My own Government, I cannot be Silent.”

- ―Martin Luther King Jr.

Revolution can be defined in many ways: social, economic, political, degree of violence, degree of change, degree of idealism, and the quality of leadership.

Why important? Because revolution, or rebellion, is a fairly unusual human behavior that requires organization and persistence, talk and action, in bringing down a sitting political power (not easy) and which people only engage in when very angry or upset about long-standing abuses. What provokes revolution is something of a mystery.

I will read at least one serious book by an historian or social scientists on revolution like the classic, “Anatomy of a Revolution” by Crane Brinton.

My key questions will be:

- What is a revolution? How can we decide on giving the label?

- Why do people rebel, revolt, and abolish governments?

- When do people become angry with their government?

- Under what conditions are they happy?

- Are rebellions and revolutions effective? Do they achieve their own goals?

- Which groups, classes, and castes of people seem to believe in revolution and which do not? Why?

- Does injustice and deprivation justify violence or not? Why? When is revolution justified or not justified?

- Would you support revolt or be revolted by it? Why? What if significant injustices are apparent?

I choose to look at photography of leaders from the Mexican, French, and American Revolutions to compare and contrast their styles. I will also offer students quotes of revolutionary ideas—ranging from conservative to liberal to radical—for them to consider which are the most exciting, reasonable, and/or effective in terms of real outcomes for their societies. We will argue about the meaning and definition of revolution throughout the unit, and I hope students will be able to develop a definition of their own that they can defend and explain in their own words. Finally, I will offer brief quotes from a dozen school or college textbooks judging or describing each revolution for students to consider in terms of differences of opinions between authors. This will enable them to make up their own minds about which revolutions were effective, or whether or not revolution can be effective in any shape, manner or form. We might do excerpts of novels or movies as well, say a selection from The Underdogs by Azuela or A Tale of Two Cities by Dickens.

I will edit materials so they are generally side by side for easy viewing and reading by students, except for the novel I will teach. None should be more than two pages in length, and preferably one or less. I will use pictures of Zapata, Villa, Madero, G. Washington, J. Adams, S. Adams, T. Jefferson, Robespierre, Marat, Danton, and Napoleon. I will also organize a discussion around “Liberty leading the people.”

Detail Questions:

- Why did Zapata dress like a caballero?

- Why did George Washington dress like a British gentleman? Why did Robespierre dress like a bourgeois lawyer?

- Why does Castro dress in cheap battle fatigues?

- Why did Mao wear a tunic?

Planning to evaluate student reactions to original quotes on revolution

We hope to see students do at least the following:

- Create and defend their own meaning of ‘revolution.’

- Compare and contrast the Mexican, American, and French Revolutions.

- Develop their own judgments, for sound reasons, of each revolution in terms of achieving its own goals, level of violence, and leadership,

- Decide on an overall attitude or philosophy of social, economic, and political change: for or against revolution, rebellion, protest, violence, organization, and form of government.

- Be able to defend their views with evidence, reasons, philosophic arguments, and references to the materials they studied.

I think the strategy that will work best for me is a combination of comparison and contrast and perspective, because this will elicit a lot of classroom discussion, bringing out a variety of viewpoints and judgments from students. I will encourage as many students to participate as possible and provide conflicting quotes if necessary. Each revolution will be studied based on a time line, documents, styles, speeches, principles, and media clips if available.

Students will demonstrate, in their work on revolutions, the following achievements:

- Express ideas clearly and in good English.

- Offer two or more definitions, one they agree with and one they criticize for reasons provided.

- Give a minimum of three reasons, with supporting data, for their judgments of revolution.

- Mention names, dates, places, people, and events they see as relevant to the overall arguments about revolution.

- Take a position on social change in which they list the reasons for their view, the reasons for an opponent, and the reasons they see as paramount in forming a decision about what is best.

Website/Book Review:

My bibliography will include several scholarly works, textbooks, original sources (Mexican, French, and American), and literature from or about the time in each nation, and visual images of revolutionaries.

French revolution in terms of leaders’ images, basic ideas, and outsider/insider evaluations:

- Arendt, H. On Revolution

- Azuela, M. The Underdogs

- Brinton, C. The Anatomy of Revolution

- de Tocqueville, A. The Old Regime and the Revolution

- France, A. The Gods are Thirsty

- Hobsbawm, E.J. The Age of Revolution: 1789–1848

- Hakim, J. A History of US: From Colonies to Country

- Paine, T. Rights of Man

Beginning a new unit: The Hero in History (you finish it)

Suggestions for much needed makeovers in the curriculum

Come up with your own

Mental Map Activity to reveal Inner Maps of Students' Important Places

Evaluation/Assessment/Diagnostics/Rubrics: Mental Map Activity to Reveal Inner Maps of Students’ Important Places

Choose one of five assignments to draw; remember this is your knowledge and your judgment. There are no right answers for a mental map. It is a map of your thinking from your perspective.

- Name and locate up to twenty of the MOST IMPORTANT PLACES in history.

- Name and locate up to twenty of the MOST WARLIKE PLACES in world history.

- Name and locate the origins of ten MOST IMPORTANT inventions.

- Name and locate the origins of ten foods you MOST like to eat and drink.

- Name and locate the ten NICEST places you would most like to visit.

This map does NOT have to be “perfect.” It is a reflection of what you think about the world at the start or end of the semester.

After drawing the rough outline of the world’s landmasses, label the places, products, inventions, living conditions you have named.

On a blank piece of paper or a bigger sheet, draw your mental map of the world. Think quickly and take no more than two minutes, that’s it! Focus on a topic or theme: REVOLUTION, POVERTY, GENDER, or RACE, then go for it. Time it!

In the space below, write about your map. What does your map tell you about how you see the world? Where and what do you know the most about? Explain why. Where and what would you like to learn more about?

Music and Lyrics Analysis Worksheet

Click to view/download the following:

Activities for the Methods Classroom

Branching Out: Wild Social Studies: Activities for the Methods Classroom

Write three DBQ middle-level questions on a topic of your choice.

DBQ inventiveness

Write three higher-order level questions that are wild, asking for high-level generalizations in history.

Develop and share five examples of what you think are brainy test questions.

How do you judge student work?

Can you create “A test NO ONE can CHEAT on”? Why or why not?