Chapter 16 - Helping the coachee raise self-awareness/self-understanding/self-honesty

Download All Figures and TablesNote Click the tabs to toggle content

Head, heart and guts

Whenever we consider a course of action we can engage thinking, feeling and willing – head, heart and guts. It may be that these different faculties give us different answers, and the unacknowledged war between them can fill us with anxiety and impede our taking action.

Your coachee can check out their reservations by seeing what message they are getting from these three aspects of themselves.

- Encourage your coachee to identify the issue.

- Encourage your coachee to consider what their head, heart and guts are telling them. As they speak, it is useful to note non-verbal cues and to feed these back.

- Example: ‘I noticed that you were talking quietly when you were saying what your feelings were. What might that be about?’

- Having explored all three aspects of their perception and choice, explore contradictions or alternatives. Is there a way of treating the alternatives as ‘both… and…’ options rather than ‘either… or…’?

- If there isn't, where is the energy? Where does the coachee feel the stronger impulse to act? What can be done about the inhibiting forces?

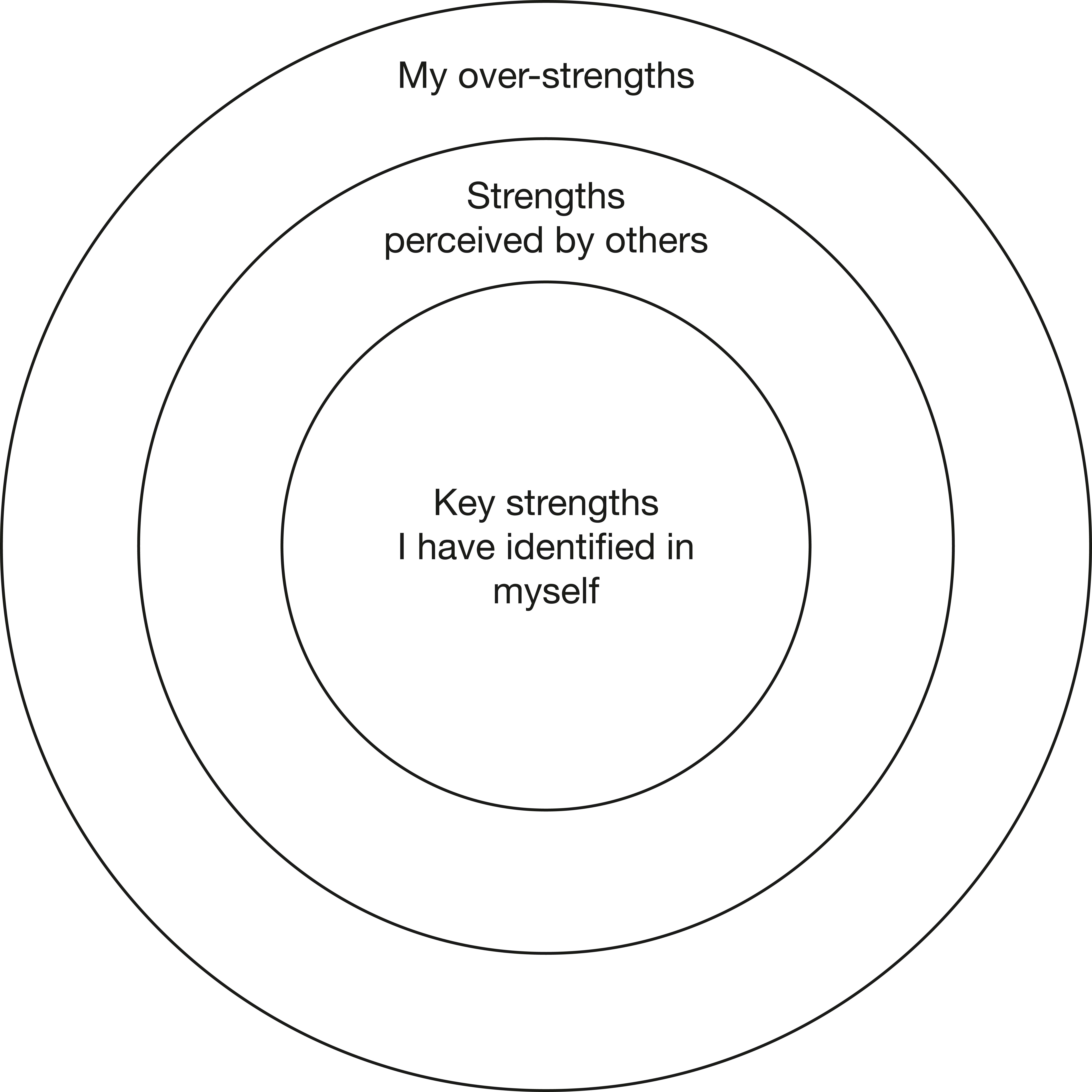

Identifying over-strengths

Over-strengths are strengths that we either use too much or use in an inappropriate setting. They can be identified using a strengths bull’s eye.

Download Figure

- Using a strengths bull’s eye (see Figure 16.1) on flipchart paper, start in the centre, brain storming your key strengths.

- Gain feedback on your strengths from other people you work with and put this on the second circle.

- Discuss these findings, recognising and valuing these strengths and explore how to build on them.

- Assess whether any of the strengths identified could be over-strengths. For example, over-conscientious – always striving for perfection, over-sensitive – taking professional feedback personally. Then note down your over-strengths in the outer column.

- Explore ways to rebalance over-strengths so they are used less often and more appropriately.

- Put the strengths bull’s eye in a place where it is seen regularly to remind you to build on your strengths and adjust your over-strengths.

Separate selves

This technique is particularly useful when they are struggling to decide a course of action, because they are experiencing inner conflict. It invites the coachee to observe consciously their different expressions of personality.

For example:

- Your optimistic self vs. your pessimistic self.

- Your active/assertive self vs. your passive self.

- Your adventurous self vs. your cautious self.

- Your serious self vs. your fun self.

- Your private self vs. your public self.

You may find clues to these opposites in any psychometrics the client has completed, but best results usually come from intuitive observation and picking up on words or phrases the client uses.

From the initial discussion, the coach identifies where there is potential or actual conflict between opposing personality traits. She or he then offers to work through the issue by taking on the role of half of the pair of opposites. For example, she or he might address the issue as the coachee’s optimistic self, while the coachee focuses on how their pessimistic self would react.

Alternatively, the coach invites the coachee to explore the issue from the perspective of one of the opposites, then the other. (Changing chairs can be helpful here.)

Identifying and challenging cognitive distortions

It’s often said that coaches should use Socratic dialogue, but this is misleading, because, while Socrates’s relentless logic revealed the flaws in other people’s thinking, it often did so through reductio ad absurdum. This earned him a lot of enemies, who eventually got their own back by forcing him to commit suicide, by drinking hemlock! A less hazardous approach is to raise the coachee’s awareness of common errors in thinking and invite them to consider when these might apply to them. This includes guided discovery through identifying the cognitive distortions, encouraging the individual to become aware of the way they are thinking. It allows identification of how thinking style can impact a given situation and how such information is to be synthesised into a series of objectives that will control future decision-making. Amongst the most common cognitive distortions are:

- All or nothing thinking – also called black or white thinking – not allowing for shades of grey.

- Magnification – over-emphasising the negative in a situation and not looking at the whole picture.

- Minimisation – reducing or discounting the positive in a situation.

- Personalisation – taking too much blame for an event happening, when actually there may have been many factors.

- Emotional reasoning – thinking something is true because you feel it to be true, rather than looking to the facts.

- Mind-reading and fortune-telling – assuming you know what someone is thinking or feeling, when actually you do not and assuming you know how an event will pan out, when you do not.

- Labelling – thinking that because you or someone else behaved in one specific way at one time, that reflects your whole personality.

- Shoulds and Musts – assuming that you and others should act the same way at all times and that everyone should live by your standards. Instead think of ‘could’ and be more flexible!

- Generalising – assuming that because one thing in a specific context didn’t work, no other things will in that context.

- Catastrophising – assuming the worst and your inability to cope with it.

- Ask the coachee to consider the consequences of adopting this type of thinking.

- Ask the coachee to complete a Thoughts Record Form (Table 16.1).

- Now challenge them to help them re-evaluate their thinking:

- Empirical or evidence based challenge: ‘Where is the evidence?’

- Logical challenge: ‘Just because you believe x, is it logical to do so?’

- Pragmatic challenge: ‘Even if x is true, do you feel better or worse for believing it and does it help you stop making mistakes?’

- Formulate a new approach to the problem encompassing outcomes from the empirical, logical and pragmatic challenging.

Table 16.1: Thoughts record form

Download TableProblem A |

Self-defeating thinking B |

Emotional/behavioural reaction C |

Healthy response D |

New approach to problem |

Giving a public lecture |

I must perform well or the outcome will be awful. |

Anxious, inability to concentrate |

Logical: Although it is strongly preferable to do well, I don’t have to. |

If I change my attitude I will feel concerned and not anxious, also, I’ll be able to concentrate and prepare for the lecture |

Grounding assessments

Grounding assessments is a questioning strategy to explore deep meaning behind statements and to investigate if there is any substance behind them. The grounding assessments procedure is an inquiry based on five questions. We have taken the statement to be a negative self-assessment as an example.

For the sake of what? What purpose does the negative self-assessment serve for the coachee or how does the assessment take care of the coachee? It is not unusual for the coachee to respond, ‘It serves no purpose’.

- In which domain(s) of life? In what specific areas of life does the assessment apply? It is important for the coach to be willing to ‘drill down’ in this question; for example, if the domain identified is work, to what specific aspects of work is the assessment relevant?

- According to what standards? Every assessment is always a comparison with standards or acceptable criteria. With negative self-assessments we are not measuring up to our own standards and it is crucial to be precise in exploring this question with the coachee by clearly articulating their standards, whether these are standards they ‘own’ or think they should have, how specifically they are not living up to their standards, and whether the standards require revising.

- What facts support the assessment? The importance of this question is to ensure that the assessment is not based on generalisations and opinions, that solid factual evidence is cited.

- What facts do not support the assessment? This question is designed to provide counter evidence of specific factual instances that contradict the negative assessment. Sometimes the coachee can identify a number of positive opinions that others have expressed of them and, while opinions per se do not count as evidence, the number of opinions cited is factual.

Through the questioning strategy coachees may find that there is no substance to negative self-assessments.

Cost–benefit analysis

This exercise helps the coachee explore how holding certain beliefs can both benefit them and prevent them from changing aspects of their life.

- Identify the current behaviour which you would like to change.

- Write down in the cost–benefit analysis form (Table 16.2) the costs and benefits of not changing that particular behaviour.

- Identify the self-defeating thinking and unhelpful beliefs.

- Reframe this thinking into self-enhancing behaviour.

Problem/behavioural tendency: Don’t seem to able to make decisions |

|

Costs |

Benefits |

|

|

Table 16.2: Cost–Benefit Analysis Form

Contingency planning

Time constraints mean that coaching tends to focus on issues that need resolution in the here and now. However, it’s also important to help the client build resilience by looking beyond the current issue and considering how they will prevent similar problems in the future.

- Identify the situation that is causing the coachee concern

- List all the potential issues and concerns that they may be experiencing with that particular situation until they cannot think of any more

- Think of a series of contingency plans against each of the concerns listed.

See Table 16.3 as an example

Table 16.3: Example of contingency planning

Download TableSituation: Giving a board presentation |

|

Situation: What could go wrong? |

Action: What will I do if this happens? |

A Experience IT problems |

Arrive early to check equipment |

B Forget my words |

Take a deep breath |

C Asked a question I cannot answer |

Simply state that I do not have the answer but that I can get it |

Changing the script

We’ve all experienced it. Those conversations where we recognise the pattern that is emerging, knowing that it is going to end negatively, but feel powerless to prevent it happening. Scripting is a powerful technique for helping break such habituated behaviours.

- The coachee describes an important conversation that has become habituated into a negative, dysfunctional pattern. Help them relive the most recent occurrence and capture the ‘script’.

- Create a table with three columns:

- What the coachee said.

- What the other person said.

- What the coachee felt.

- Encourage the coachee to capture the script next time it is played out. The coachee selects a point in the script where they would like to make a change.

- You can discuss with them how that relatively small change can be achieved and they can try this next time the script is in danger of being replayed.

- As they become confident in changing one element of the script to be more positive, they can move onto another until the whole conversation is different.

Keeping a log of highs and lows

Our lives are full of repetitive patterns, of which we are largely unaware. At one extreme, for example, is the coachee, who time and again starts a new job with enthusiasm and high performance, then, when they are at the height of their success, appears to self-sabotage and is forced to move on. Yet it takes a coach to help them recognise that this pattern occurs and to consider why. At a more mundane level, personal effectiveness is affected by a host of behaviours in ourselves and others – for example, how well we prepare for some meetings compared with others. Recognising common patterns here allows us to develop remedial strategies. Keeping a log of the highs and lows of each week creates a resource, through which repeated patterns become more obvious.

- The coachee takes time to reflect each week on the things that have happened to them – either at or outside work and in the coaching session.

Issues the coachee may record in their blog include:

- Personal fulfilment : What has really frustrated you/pleased you this week? What encouraged/discouraged you? What tasks made you feel ‘in flow’?

- Completion: What tasks did you complete today? What did you leave incomplete? What did you avoid completely?

- Insight: What did you get to see differently? What have you learned about yourself?

- Resourcefulness: Who did you add to your networks? What skills or processes did you learn?

- Behaviour: Did you consciously change the way you behave in some way today? What was the result?

- Goal fulfilment: What did you do today to take yourself towards longer-term goals?

- Decisions: What significant decisions did you make today? How do you feel about them?

- Challenge: Who or what did you challenge today?

- They write a short descriptive paragraph about each: what happened, who was involved, how they felt, how they prepared, etc.

- Once they have two or three weeks’ worth, they can begin to look for recurrent patterns.

- The coach can review the log and notice patterns they had not noticed. These patterns – and sometimes specific instances in the log – become the basis for fruitful coaching conversations.

The mindset for learning

People with fixed mindsets assume consciously or unconsciously that there are some things they are good at and some they are not good at, and that their ability is effectively set in stone. They therefore tend to avoid challenges which take them into their areas of perceived weakness, or where there is a risk of failure. People with growth mindsets see themselves as having potential in a wide range of areas. They relish the opportunity to stretch their ability, regardless of whether the subject is one where they are ‘naturally’ talented. Failure to them is just a step on a learning journey.

Whether a manager has a predominantly fixed or growth mindset will likely have a substantial impact on how they face up to (or avoid) situations which are complex, involve high degrees of uncertainty, or simply stretch them beyond their comfort zone. If a manager seems to be resistant to the coaching process, making little progress in tackling their issues, then mindset is one area the coach might usefully explore.

Ask the coachee the following questions to determine if they have a fixed or a growth mindset:

- Tell me about how you define talent in the people around you? … Leading to … How do you describe yourself in terms of talent?

- Tell me about a time when you were faced with an apparently insoluble problem. How did you tackle it?

- How do you decide when to stick with a problem until it’s solved and when to decide there’s no point in putting in more time or effort?

- How important is it to you to be right?

- What excites you about taking on new responsibilities?

If the pattern of responses indicates that the coachee tends towards a fixed mentality, then the coach/mentor can help them become aware both that this is the case and what the implications are for tackling the issues which the coaching/mentoring relationship is intended to address.

Sharing the concept of the two mindsets provides a language which they can use to explore or prevent impasses, by asking questions such as:

- If we were having this conversation from a growth mindset, what would we be saying differently?

- Which mindset do you want to apply here? (Do you feel that you have the power to choose your mindset?)

Entrepreneurial preferences

One of the most common developmental issues at senior levels is that the organisation wants a coachee to become more entrepreneurial. But what does that mean? And how do you facilitate someone in developing skills which may be innate and/or personality-based?

It is useful to break down the entrepreneurial process in such a way that the coach or mentor can help a coachee identify where they have instinctive capabilities and preferences, and where they need support from other people who have different strengths. In other words, how can they establish a cooperative grouping, which will deliver the required entrepreneurial behaviours?

There are a number of capabilities required, each representing a different stage of the process. The immediate need of the coachee will usually be to work out what is lacking in their entrepreneurial inclinations. The coach can help by discussing each stage of the entrepreneurial process and how the coachee approaches them.

The aim is to help the coachee recognise why they sometimes fail to turn good ideas into good outcomes and to develop practical ways for them to be more effective – and to be seen to be more effective – in the future.

Here are the stages and some useful questions for each one:

Opportunity recognition

- Having innovative ideas: In the main, these are not blue-sky, off-the-wall, but extrapolative thinking – for example, seeing new applications for existing technologies, or seeing the potential for putting together two or more existing ideas or processes.

- Adapting ideas: Moving from the theoretical to the practical. Here, the entrepreneur uses creativity and experience to find ways to turn the idea into a saleable product, a reproducible process and so on.

Questions the coach can ask:

- Do you often wake up with original ideas?

- Do you frequently see potential new business opportunities?

- Do you habitually see possibilities where other people see problems?

- Do you easily combine ideas to produce a new approach or perspective?

- When and how have you been an active participant in coming up with innovative ways forward?

- Do you see ways in which half-thought-through ideas could be turned into something more practical?

- Have you ever found ways to capitalise on ideas that didn’t work before, so that they will work in a different context?

- Do you find you can borrow from other areas of expertise to make an idea more workable?

- Do other people use you as a sounding board for their ideas?

Coalition-building

- Networking: Finding and bringing together people who will provide advice and help develop the concept.

- Alliance-building: The politics of gaining support from people, who will cooperate in making the project work.

Questions the coach can ask:

- Do you find it easy to identify people who might be useful to you?

- Do you usually know where to find a source of advice or help for the business issues you encounter?

- Do you actively construct and maintain networks?

- Do other people want to be networked with you?

- Do you find it easy to identify what’s in it for other people to collaborate with you?

- Do you enjoy the politics of keeping people ‘on side’?

- Do other people see you as a source of influence or opinion former?

- Do you often act as the bridge between groups with different interests?

Development

- Product development: The detail of making the product or process market-ready. Conceptual thinkers often have lots of ideas, but lack the patience and focus to carry them through. Product development may also include figuring out how to make money from the innovation.

- Route to market: Developing a clear understanding of who will buy the product and why; of how to reach them; and of the psychology of the sale.

Questions the coach can ask:

- Do you frequently work through and test the logic of proposed innovations?

- Do you enjoy working at an idea until it feels completely ‘right’?

- Are you good at following through the implications of ideas until you have mapped out all the details?

- Are you adept at ‘packaging’ a concept or product so that it is professionally presented?

- Can you visualise clearly who will buy a new product and why?

- Do you systematically investigate and define the intended market?

- Do you have the skill to distinguish between what you would like to believe about the market and what the evidence says?

- Do you instinctively work your networks to find people who will be intermediaries to the market?

Resourcing

- Acquiring Funding: The financial wherewithal.

- Acquiring Permission: In an intrapreneurial context, the sign-off from key resource holders in the organisation.

- Acquiring Expertise: In the form of people and other stores of know-how.

Questions the coach can ask:

- Can you usually find a ‘crock of gold’ for something worthwhile?

- Can you persuade people, who hold the purse strings, to back your judgement?

- Are you good at getting things done on an inadequate budget?

- Do you find it easier to ask for a lot of money than for a little?

- Do you often work on the principle of seeking forgiveness rather than permission when you know something needs to be done?

- Do you often maintain support for a project by tackling it through small increments which appear less of a risk or threat?

- Do you have a good mental picture of the skills and experience of the people around you?

- Do you usually know where to turn for specific expertise, directly, or through your networks?

- Do you frequently make a mental or physical note of a resource that might prove useful in the future?

- Are you good at persuading other people to give you access to resources they control?

Risk-management

- It is common to confuse the audacity and creativity of innovation with taking great risks. In reality, successful entrepreneurs tend to be relatively risk-averse. The risks they take are considered and calculated rather than instinctive or reckless. Once a decision is taken, however, they are typically impatient to see it implemented.

As a coach, you will need to ask:

- How would you describe your attitude towards taking risks?

- Do you have a good understanding of and skill in using risk management processes?

- Are you often taken by surprise by failures which you had not imagined?

- Can you easily describe and quantify for your own and other people’s benefits the risks of failure and the risks of success?

Action-orientation

- Championing the changes: Taking ownership for them, promoting them at every opportunity.

- Inspiring others to action: Instilling a sense of urgency in others.

- ‘Stickability’: Working through setbacks with determination.

- Chasing change: Ensuring that support is maintained, that barriers to making it happen are overcome.

Questions the coach can ask:

- Do you take visible ownership for projects or ideas you want to succeed?

- Do you take every opportunity to talk about them to relevant other people?

- Are you prepared to risk your own reputation by championing the project or idea?

- Do people typically see you as a leader or follower of change?

- Do you demonstrate a strong belief in ideas you espouse?

- Are you perhaps a little obsessive about them?

- Do you communicate a sense of urgency about the project or idea?

- Do you listen to and work with other people’s concerns about the implications of change?

- Do you get easily discouraged if nobody seems interested?

- Do you get easily distracted by the next new idea?

- How do you sustain your own enthusiasm as the project progresses?

- How do you decide when enough is enough?

- What strategies and processes do you use to sustain other people’s enthusiasm?

- Can you easily predict when projects or people are likely to ‘go off the boil’ and take preventative action?

- Do you monitor progress closely without getting bogged down in detail?

- Do people keep you informed of progress or do you have to go find out?

Having clarified with the coachee where their natural entrepreneurial inclinations are strongest, the coach can help with questions such as:

- How can you make sure there are more ideas to consider, even if you don’t create them yourself? (How can you encourage people to bring you more ideas?)

- What can you do to question established ways of doing things?

- What could you do to improve your networking skills?

- How can you identify and attract the right coalition partners?

- Who will flesh out the idea, if you don’t?

- What expertise do you need to tap into, to ensure there really is a market and that it is prepared for this idea?

- What’s your strategy for getting the money to make this happen?

- What’s your strategy for making it less threatening?

- What will your ideal team for this project look like?

- How will you establish and manage the risks?

- What behaviours would you expect from a change champion?

- How will you capture and sustain your own and other people’s enthusiasm?

- How will you get over the inevitable setbacks?

The Five whys

The five whys is a simple technique for assessing motivations and making decisions. It begins with the question Why do I want to do this? And keeps asking why until a much more comprehensive picture emerges. A typical cascade might be:

- Why do I want to take a degree? To be more qualified in my role.

- Why do I want to be more qualified in my role? To earn more money.

- Why do I want/need to earn more money? To pay the mortgage.

- Why do I need to pay a mortgage (why not rent)? Because I want the security of owning my own home.

- Why do I need security? Answer?

The cascade of whys almost invariably leads the discussion to a deeper level of reflection that encompasses values and self-identity.