Chapter 2 - Getting ready for the coaching session

Download All Figures and TablesNote Click the tabs to toggle content

Am I (the coach) in the mindset for coaching?

Hawkins and Smith (2006) suggest that the coaching session starts from the moment the coachee and coach meet – the informal greetings and preparation can be very informative about the coachee’s state of mind. However, it is important to note that the coach needs to pay attention to his or her own state of mind as well, and this attentiveness may need to start well before the session. Before coaching, ask yourself these questions:

- Am I truly ready for coaching? (Am I relaxed, attentive and able to focus fully on their issues?)

- What personal baggage am I in danger of importing into this conversation?

- What do I already know about this coachee, which may prevent me being as helpful as I’d like?

- What does my body tell me about my own mental state?

- If you are not feeling completely at ease, use relaxation techniques to alter your frame of mind before the coachee arrives.

- Ensure that back-to-back coaching does not happen and you have time to reflect and relax before the next coaching session.

Am I in equilibrium? (Both coach and coachee)

A mental state of high alertness, combined with relaxation stimulates awareness of both self and each other, better listening behaviours and positive attentiveness. Most people are rarely in this ‘true equilibrium’. A practical way of achieving this is to take time to reflect where you are on nine areas of balance:

- Doing vs. being: Doing refers to our behaviours and actions; being is about our sense of identity and awareness of self. Key to establishing equilibrium here is to take time occasionally to slow down, both mentally and physically, until you are calm enough to take note of everything within and around you.

- Me space vs. them space: Allowing both action time and thinking time for oneself, rather than allowing all our attention to be taken up with things we do for or on behalf of others.

- Past, present and future: Is your mental attention appropriately distributed between these temporal perspectives?

- Balanced vs. unbalanced body: Very few people have perfect posture. How we sit, stand and move has a strong impact on how we feel and vice versa. Checking for positive posture is a useful habit for any activity, from sports competition to a coaching conversation.

- Participating vs. observing: We all have a natural inclination to either get stuck in or watch from the sidelines. Effective coaching – from the perspective of both the coach and the coachee – requires a conscious moderation to avoid going too far to either extreme. Part of this is the balance between talking and reflecting quietly.

- Knowing vs. innocence: Some knowledge is important in shaping the conversation, but both coach and coachee need also to cultivate a degree of naivety, from which spring penetrating questions and honest responses.

- Accepting vs. judging: It’s common for pundits to say that coaches should never make judgements about people and situations. That’s delusional, of course; unconsciously, we are all making judgements all the time. Raising our awareness of where we may be prone to make judgements and whether those are justifiable on the evidence, promotes openness in the coaching conversation.

- Support vs. challenge: Coaches can usefully attend to how they balance their support and challenge. An appropriate point on the scale will differ from coachee to coachee and from time to time with any one coachee.

- Concrete vs. abstract: Some coachees focus on immediate issues or defined projects and find abstractions difficult. However, if they are to generalise their learning they will need to make broader sense of their immediate learning. By contrast, others like to deal in abstractions and the coach/mentor’s role is to help them focus on grounding their learning, for example by answering the questions: What? So what? Now what?

Reflecting on these balances creates a set of positive expectations of a coaching conversation. It also helps ensure that both coach and coachee are able quickly to enter flow.

Ascertaining the state of the coachee

It’s easy to assume that a coachee is ready for coaching, but are they in a calm mental state ready for reflection? A lot can be deduced from simply observing the coachee as the introductions take place. Does their body language indicate that they are relaxed and open, or tense and suspicious? Does their verbal language suggest openness and reaching out to you, or reserved aloofness, eagerness to learn or fear of being found out?

In the initial ‘getting to know you’ conversation with the coachee ask the following questions to assess their coaching readiness:

- What do you expect coaching to do for you?

- Who else has an agenda for you to address through coaching? What do they want you to do or achieve? What do you think/feel about this?

- What fears or concerns do you have about the coaching process?

- What previous experience have you had of being coached? What was positive and negative about it?

- What is your energy level for coaching right now?

- Where and how do you find time to think?

- What does it feel like when you are able to be honest with yourself? Is that something that happens frequently?

- How do you learn complex things?

- How comfortable do you feel with the ‘constructive chaos’ of creative thinking?

- Do you want coaching to focus on the really big, scary issues or on everyday problems? How do you feel about moving from one to the other in the same conversation?

- How much challenge can you honestly take? What would other people say?

Raising the coachee's ability to be coached

This exercise is designed to make the coachee aware of how they can raise their own ability to be coached. The coach can use standard scaling techniques to help the client work out where they are on the issues that seem most significant to them. Are they willing/capable/committed to:

- Spend at least 30 minutes on the day of the coaching session, or the day before, putting their thoughts in order and prioritising them on an urgent/important matrix?

- Consider how they can best express these so that the coach can be as helpful as possible?

- Carve out 10 minutes of quiet space immediately before the coaching session, where they can ensure that they are in the right mindset for coaching – i.e. calm, creative, curious, anticipatory?

- Share with you any relevant materials, such as performance appraisals, 360 feedback, or psychometric tests that they have taken?

- Reflect when something has been particularly successful or unsuccessful, or where they feel they have been either at their best or their worst, and consider this in light of the purpose or goals of the coaching relationship?

- Take reflection notes on self-observations, if you have asked them to practice different behaviours?

- Explore issues from an emotional perspective and find ways to use emotions to support them in achieving their goals?

- Address issues that they have avoided thinking about?

- Be as authentic as they can?

- Take the risk of open disclosure and self-honesty?

- Be as honest as they can with you and explore with you if they are being less than honest?

- Take time to pause and reflect when a point strikes home.

- Spend at least 30 minutes within the following 24 hours after a coaching session in deeper reflection about what they have learned. Useful questions include:

- What have I learned that will help me achieve my objectives?

- Who else do I want to talk to about these issues?

- What do I know and not know?

- What further information do I want to gather?

- What am I going to do (differently) between now and the next coaching session?

- Use the coach between sessions for brief virtual conversations (telephone, Skype, email, text and so on)? For example, to use them as a sounding board for how you are going to approach a difficult meeting; or to check your understanding of a management model that you have discussed together.

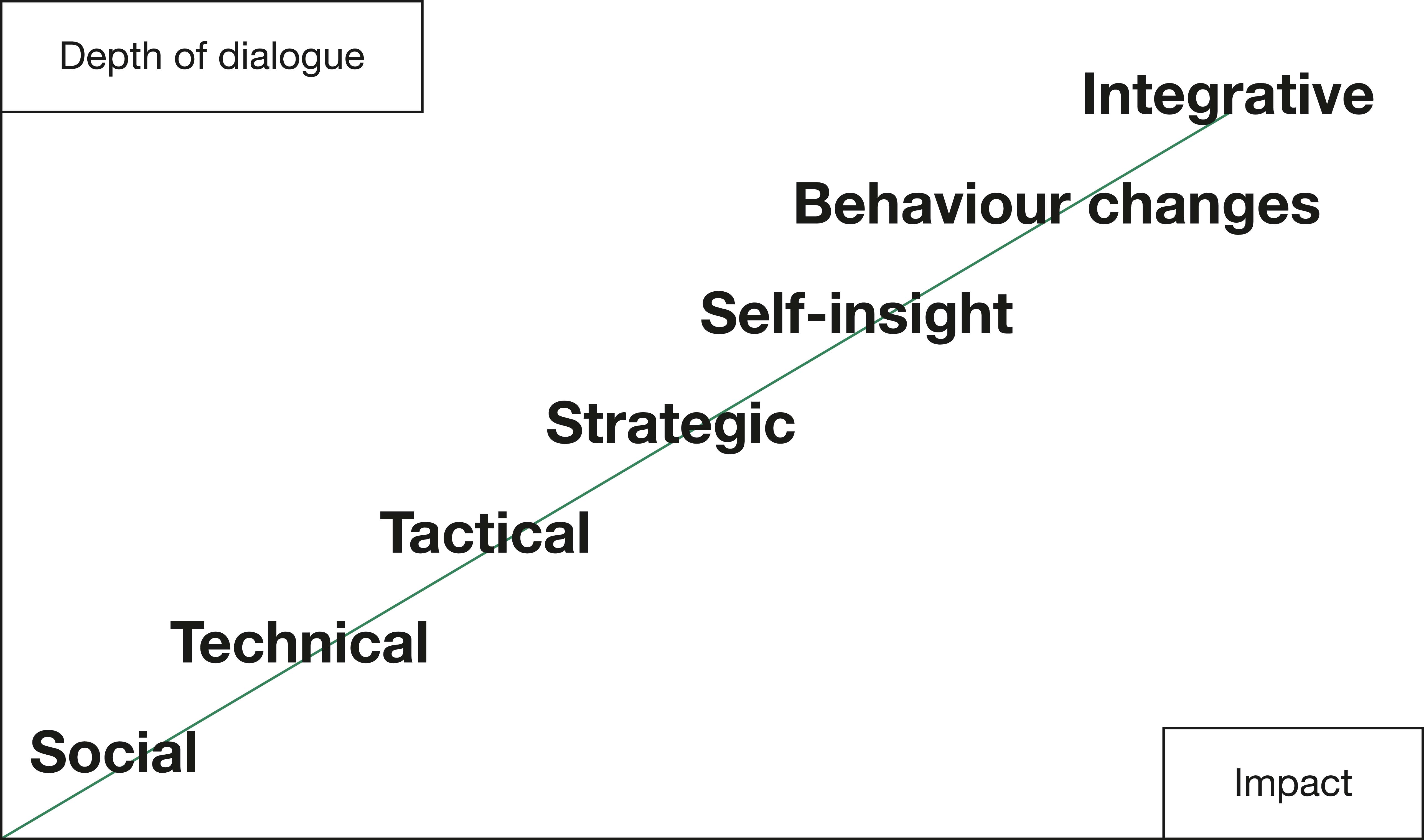

- Be comfortable with each of the seven layers of dialogue (see page 35) (the coachee should aim to be comfortable with all seven!)

In addition or alternatively, ask the coachee:

- What do you think are the hallmarks of an effective coachee?

- What can you do to make sure that you get the most out of this coaching/mentoring relationship?

Preparing for coaching

One of the most common reasons coaching results in stress and anxiety for the coach is that they (and/or the coachee) enter the conversation in the wrong frame of mind. If they arrive at the session with emotional baggage that will distract them, or hastily completing important messages on their laptop or mobile, it makes for a much less effective session than when both parties have a mind state of relaxed and creative focus. Once again, there are many ways to achieve this, from formal meditation before sessions, to generating laughter. One of the quickest is for the coach and the coachee to close their eyes and breathe deeply, then to relax at least one muscle in their bodies and to let go of at least one emotion or concern they have brought with them. This simple procedure can radically and immediately improve the dynamics of the learning dialogue.

Three-minute breathing space

This is one of the simplest and quickest ways to ensure you enter the coaching conversation in an alert but relaxed and mindful state of mind. The key steps are:

Acknowledging:

Bring yourself into the present moment by deliberately adopting an upright and dignified posture. Then ask yourself: ‘What is going on with me at the moment?’

Acknowledge your current experience. As best you can, accept whatever you’re experiencing, in thoughts, feelings or bodily sensations. Stay with these experiences for a few moments allowing any negative feelings of experiences to be just as they are.

Gathering:

Gently focus your full attention on breathing. Experience fully each in-breath and each out-breath as they follow one after the other. Let the breath be an anchor to bring you into the present and to help you tune in to a state of awareness and stillness. When the mind wanders, as it will, gently bring it back to the breath.

Expanding awareness:

Expand your awareness around the breathing to the whole body and the space it takes up. Feel your whole body breathing. Have a sense of the space around you. As best you can, hold your body sensations, feelings and thoughts in a broad awareness. Let things be, just as they are.

Coaching as a three-stage process

Bob Garvey, of York St John University, has applied Egan’s therapeutic model to coaching, seeing it as a three-stage process of exploration, new understanding and action. Use the three-stage process to:

- Think about your route.

- Find where you are when you get lost.

- Choose another route.

- Make choices about direction and destination.

Stage one

Strategies for exploration

- Take the lead to open the discussion.

- Pay attention to the relationship and develop it.

- Clarify aims, objectives and discuss ground rules.

- Support and counsel.

Methods for exploration

- Open questions.

- Listening, listening and listening.

- Developing an agenda.

- Summary.

Stage two

Strategies for new understanding

- Support and counsel.

- Offer feedback.

- Coach and demonstrate skills.

Methods for new understanding

- Listening and challenging.

- Using both open and closed questions.

- Helping to establish priorities.

- Summary, paraphrasing, restating, reframing.

- Helping identify learning and development needs.

- Giving information and advice.

- Sharing experience and story telling.

Stage three

Strategies for action

- Examine options and consequences.

- Attend to the relationship.

- Negotiate and develop an action plan.

Methods for action

- Encouraging new ideas and creativity.

- Helping in decisions and problem solving.

- Summary.

- Agree action plans.

- Monitoring and reviewing.

- Giving and receiving feedback about the relationship and the meeting.

Tolerating ambiguity

One of the most common reasons coaching sessions lack creative thinking is that the coach, the coachee or both close down interesting and potentially valuable areas of exploration. Some of the reasons for this are that they:

- Are too eager to get to a solution, when putting the issue into a wider or different context might open up different possibilities.

- The coach assumes they know ‘the answer’ to the coachee’s issue. They then run the risk of second-guessing the coachee and asking leading questions (suggestions disguised as questions – these are sometimes referred to as ‘queggestions’). A favourite example is: ‘Have you thought about trying …?’

A simple technique for raising awareness during the coming conversation is to spend a few moments imagining the client and asking ‘What is going on inside them and what is going on in their external world?’ For each thought that arises, ask ‘And?’ or ‘What else?’ It takes less than a minute for most coaches to become more attuned to holding more options in mind and to asking questions that open up possibilities, rather than close them down.

Taking notes in coaching and mentoring

In meetings, people often take copious notes. The problem is that the more notes you take, the less you attend. Our brains don’t have dedicated circuits for writing, so they have to cannibalise circuits that would otherwise be used for listening.

Coaching requires intense listening skills and mindfulness. The coach needs to be fully present and attentive. So taking notes in the flow of the conversation isn’t recommended. Instead, take advantage of occasional pauses in the conversation to invite the coachee to summarise the key points of what has been said. This has the advantage that it captures what they think is important (not what you think) and gives you deeper understanding of how they are making sense of their issue. You can, of course, then offer some thoughts of your own, if you think this is helpful.

Capturing the thoughts from this summary (in writing) gives a much more useful and focused picture of what’s important and insightful. Both you and the coachee can subsequently use the notes you take during these summaries (you might have up to 10 summaries over the course of an hour) for reflection.

Helping the coachee to summarise

In some of the earliest observations of mentors, David Clutterbuck identified a number of major differences between the most and least effective. One was that the least effective tended to summarise more often than the mentee and to summarise at the very end of the session. In doing so, they took away responsibility and control from the mentee. While it is clearly appropriate for the coach or mentor to summarise at certain points in the conversation, a core skill is enabling the client to take the overall lead in summarising.

For brief summaries, useful questions include:

- What strikes you about what we’ve just been saying?

- What words and phrases carry most significance for you?

- How are you feeling about the past few minutes?

- What themes are emerging here?

- What are you becoming curious about?

At the end of the session, the four ‘I’s provide an efficient method to review the conversation:

- Issues (what did we discuss?).

- Ideas (what creative thoughts did we have?).

- Insights (what new understanding emerged?).

- Intentions (what are you going to do as a result of this conversation?).

Managing constructive challenge

When coaches and coachees review their relationships, one of the most common issues that arises is lack of constructive challenge. Both parties often report that the other is not tough enough in questioning their assumptions, beliefs and behaviours.

The depth and quality of constructive challenge has its origins in the first coaching conversations, where coach and coachee establish expectations of each other. It’s important to agree something along these lines:

- I will always give you honest feedback about what I observe and hear in our conversations.

- I will question whenever I feel that a statement, opinion or assumption is not fully thought through.

- I will challenge whenever I perceive a divergence of values.

- I will welcome and give open consideration to constructive challenge.

- I will always seek to challenge with respect (i.e. in a way that does not undermine your self-esteem).

- Knowing when to challenge.

- Knowing what style of challenge to employ in different circumstances.

- Having the courage and appropriate language to make the challenge.

- Is the person receptive to challenge right now? Is there a time when they will be more receptive? For example, when there are other people present, the other party in the coaching relationship is liable to be much less receptive.

- Where possible, try to challenge ‘in the moment’. Saying something like ‘You know, that makes me feel very uncomfortable’ will have more impact, if you do so immediately after they have spoken.

- Don’t flood the other person with challenges. If the aim is for them to reflect deeply on a new insight, then additional challenges will dilute their thinking.

- Permission to explore.

- Fearless questions.

- Sharing responsibility for the issue.

- Analysing assumptions, behaviours and values.

- Achieving clarity.

- Using silence.

- Valuing the insights that come from different perspectives.

- Help them maintain their self-esteem.

- Their behaviour, not their person (e.g. ‘What were you trying to achieve by being aggressive to John?’ rather than ‘You just behaved like a bully.’).

- Their assumptions, not their intellect (e.g. ‘What assumptions were you making about this issue?’ rather than ‘Did you really think that was clever?’).

- Their perceptions, not their judgement (e.g. ‘How did you see that meeting?’ rather than ‘You lost it there, didn’t you?’).

- Their values, not their value (e.g. ‘How does that decision square with your personal beliefs about how to treat other people?’ rather than ‘I’d expect that kind of ethics from an ambulance chaser!’).

The key skills of constructive challenge are:

Knowing when to challenge

Useful guidelines here include:

Knowing what style of challenge to employ in different circumstances

The challenging vs. supporting matrix (Table 2.1) shows four different situations the coachee may bring to the coaching sessions. Sometimes the mentee just needs support; sometimes to be stretched. Sometimes they need empathy; sometimes a higher level of objectivity.

Download Table

|

Empathy |

Objectivity |

Challenging |

Stretching horizons – giving encouragement and self-belief |

Direct feedback about areas of conscious or unconscious development need |

Supporting |

Encouraging when things get tough |

Pragmatic steps to plan solutions |

Table 2.1: Challenging vs. supporting matrix

Selecting the right mode for the coachee is a core skill for coaches.

Having the courage and appropriate language to make the challenge

Having the courage is partly a function of psychological safety (how confident you feel that the other person will accept and welcome the challenge and how reassured that there will be no negative consequences from it) and partly confidence in your own ability to manage the conversation.

Key elements in giving appropriate challenge – as with any difficult conversation – are:

By getting them to agree to discuss an issue, you begin to create a more open mindset (e.g. ‘I’d really value an opportunity to talk about…’).

Questions that challenge in a constructive way, removing blame from the conversation and allowing space for the person to respond constructively.

A useful phrase here is ‘what would help you to understand…’ because it suggests less direct criticism on your part and a willingness to countenance their perspective.

Examining their assumptions, values and behaviours by asking pertinent questions (e.g. ‘What do you think are the motivations of the other people involved in this?’).

Frequent checks on understanding (e.g. ‘Have we both taken the same meaning from the conversation so far?’).

Give them space to reflect upon what is being said, to avoid knee-jerk responses to criticism.

Demonstrate that you are open to their point of view, while reserving the right to maintain your own.

Challenge:

Setting expectations: The sound of silence

One of the beneficial side effects of coaching is that the client learns to place greater value on quiet thinking time. Coaching sessions provide a safe environment to practice using silence. In fast-moving Western business cultures, particularly, this is an art that is easily lost. Indeed, people are so uncomfortable with silence, that they frequently feel obliged to say something to break it.

Coaches have a responsibility to assist clients in using silence and one way of doing so is to be a role model for holding back on automatic responses. A simple but effective exercise is to count to three after the client has stopped speaking, before responding. Frequently, the client will continue to explore an issue without prompting, within those three seconds or so. Once you are comfortable with three seconds of silence, gradually increase the length of your silences and observe the effect.

- The coachee hasn’t decided what they want to talk about.

- The coachee needs to establish some inner calm in order to address an emotionally difficult issue.

- The coachee is open to the concept.

- If asked a difficult question or a point has just ‘struck home’, the coach will give the coachee time to think about what was said and reflect before moving forward.

The seven layers of dialogue and how to develop them

We tend to think of conversations as all being the same, but this is far from the case. For a start, there is a difference between debate (where the aim is to win other people over to your point of view), discussion (where the aim is to achieve a consensus) and dialogue (aimed at achieving new meaning). Coaching sits firmly within dialogue, but even here there are multiple types and purposes, which we describe below. Most coaches have a preference for some of the seven types of dialogue over others and this can profoundly influence the clients and issues they choose to work with and how they manage coaching conversations. Recognising these preferences (and those of our clients) provides valuable insights. Extending the range of our dialogue preferences enhances our coaching overall.

Download Figure

How to develop social dialogue

- Demonstrate interest in the other person, in learning about them.

- Actively seek points of common interest.

- Accept the other person for who they are – virtues and faults, strengths and weaknesses.

- Be open in talking about your own interests and concerns.

How to develop technical dialogue

- Clarify the task and the coachee’s current level of knowledge.

- Be available when needed (just-in-time advice is always best).

- Be precise.

- Explain the how as well as the why.

- Check understanding.

How to develop tactical dialogue

- Clarify the situation (what do and don’t we know?).

- Clarify the desired and undesirable outcomes.

- Identify barriers and drivers/potential sources of help.

- Establish fall-back positions.

- Provide a sounding board.

- Be clear about the first and subsequent steps (develop a plan, with timeline milestones).

How to develop strategic dialogue

(The coach uses the same skills for tactical dialogue plus the following.)

- Clarify the broader context (e.g. who are the other players in this issue?).

- Assess strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats.

- Explore a variety of scenarios (what would happen if…?).

- Link decisions and plans closely to long-term goals and fundamental values.

- Consider radical alternatives that might change the game (e.g. could you achieve faster career growth by taking a sideways move into a completely different function?).

How to develop dialogue for self-insight

- Ensure the coachee is willing to be open and honest with himself/herself.

- The helper merely opens the doors: it is the coachee’s journey of discovery.

- Give time and space for the coachee to think through and come to terms with each item of self-knowledge.

- Be aware of and follow up vague statements or descriptions – help the coachee be rigorous in their analysis.

- Explore the reasons behind statements – wherever possible, help the coachee establish the link between what they say/do and their underlying values/needs.

- Introduce tools for self-discovery – for example, self-diagnostics on learning styles, communication styles, emotional intelligence or personality type.

- Challenge constructively – ‘How did you come to understand how/why…?’.

- Give feedback from your own impressions, where it will help the coachee reflect on how they are seen by others.

- Help the coachee interpret and internalise feedback from other people (e.g. 360 appraisal).

How to develop dialogue for behavioural change

(The coach uses the same skills for self-insight plus the following.)

- Help the coachee to envision outcomes – both intellectually and emotionally.

- Clarify and reinforce why the change is important to the coachee and to other stakeholders.

- Establish how the coachee will know if they are making progress.

- Assess commitment to change (and if appropriate, be the person to whom the coachee makes the commitment).

- Encourage, support and express belief in their ability to achieve what they have committed to.

How to develop interactive dialogue

- Explore multiple, often radically different perspectives.

- Shift frequently from the big picture to the immediate issue and back again.

- Ask and answer both profound and naïve questions (often it is difficult to distinguish between them).

- Encourage the coachee to build a broader and more complex picture of him/herself, through word, picture and analogy.

- Help them write their story – past, present and future.

- Analyse issues together to identify common strands and connections.

- Identify anomalies between values – what is important to the coachee and how the coachee behaves.

- Make choices about what to hang on to and what to let go.

- Help the coachee develop an understanding of and make use of inner restlessness, and/or help them become more content with who and what they are.

The most effective coaches invest considerable time and effort in building their repertoire of skills so they can both recognise the appropriate level of dialogue to apply at a particular point. This engages the coachee appropriately.

Setting the direction

- Make note of the questions you (the coach) ask in a session, and briefly the responses of your coachee.

- After 10 minutes or so, suggest to the coachee that you stop and review where the conversation has gone and where it could most usefully go for them next.

- Pursue this direction.

- Stop after another 10 minutes and check again. The coachee may want to continue and perhaps deepen the direction that you have taken, or they may wish to branch out again.