The Minor

The Public Ledger 1760 July 14, Vol.1 No.158.

The author provides a brief notice of publication of The Minor along with a commendatory reflection on Foote and his play.

From The Minor

The London Chronicle 1760 July 31–Aug 2,Issue 562

The author makes a few general but favorable remarks on The Minor, followed by a synopsis that focuses on the metatheatrical aspects of the play.

From The Minor

Foote, the Devil, and Polly Pattens. Published in The Macaroni & Theatrical Magazine 18 Feb. 1773.

The Victoria and Albert Museum, London. Foote took up the torch as patentee at Fielding’s old Little Theatre, Haymarket, but tore down the old theatre and rebuilt a new one on the same site, with a capacity of a thousand, after his first season. To recover his costs he asked to have his license extended past the summer season; when it was not, he went around the licensing laws (something he had done before with his morning “concerts” and his Dish of Tea and Dish of Chocolate performances by presenting a satirical puppet show in February 1773. Alternately called, The Primitive Puppet Show and The Handsome Housemaid, or Piety in Pattens, the play parodied sentimental comedy, acting styles in general, and David Garrick, with Foote voicing most of the puppets. When asked whether the puppets were life-size, Foote allegedly replied by saying that there were not, as they were not much bigger than David Garrick. Garrick nonetheless attended the show and praised Foote’s genius.

From The Minor

Anon., The Rev. Mr. Whitefield Preaching at Leeds, 1749.

Courtesy of the Lewis Walpole Library, Yale University. This anonymous image shows Whitefield preaching before a crowd in Leeds. His arms are spread wide in an approximation of a theatrical gesture, and he holds his handkerchief, a reference to his frequent practice of crying during his own sermons.

From The Minor

“Squintum’s Farewell to Sinners,” London: M. Darly, 1760.

Courtesy of the Lewis Walpole Library, Yale University. This print, which appeared after Foote’s satire, shows how firmly the name “Squintum” stuck to Whitefield. Whitefield addresses the primarily female crowd with a sermon declaring “my great, my strong love for you” while various women respond. One exclaims “Oh! Dear Squintum! Let me come under your direction,” while another wonders “I don’t know whether Squintum or my soldier has got me with child.” Another says she has pawned her last for her two favorites, “gin and Squintum,” while other women are more suspicious of his message.

From The Minor

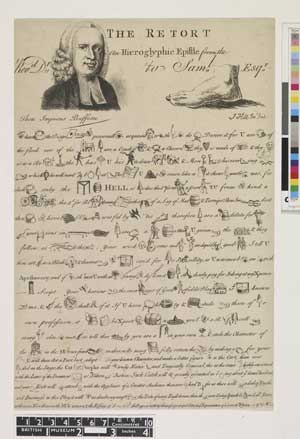

The Retort, an Hieroglyphic Epistle from the Rev. Dr. [Whitefield] to Saml [foot, i.e. Foote] Esqr. J. Hill Invt. Scul. Trustees of the British Museum.

This satirical rebus comments on the print war between the supporters of Whitefield and those of Foote. While Whitefield only made one mention of it in his letters, it seems clear that his supporters, perhaps at his urging, were quick to defend him in print. A long series of articles and letters in Lloyd’s Evening Post in 1760 brought John Wesley into the fray; he responded November 17–19 with a letter of his own. This print was advertised in the Public Advertiser December 6, 1760.

From The Minor

“Miss Macaroni and her Gallant at a Print Shop.” J. Smith fecit, printed for John Bowles, at No. 13 in Cornhill, published April 2, 1773. Courtesy of the Lewis Walpole Library, Farmington, CT.

The image shows a fashionable young woman (a female “macaroni”) admiring prints that feature scenes from popular plays along with popular preachers, including John Wesley and George Whitefield.

From The Minor