Sustainable Design

Thematic Essay

Click to download

‘I’m Not Just Another Reusable…’ Sustainable Design Beyond the Tote Bag

Rachel Beth Egenhoefer, University of San Francisco, USA

When I tell people that I teach “Sustainable Design”, I’m often met with confusion. These two words are used in a variety of circumstances, to describe a variety of things. On a basic level, most people associate design with things you see and touch: graphics, websites, fashion, products, and architecture. Likewise, some think of sustainability as simply recycling, solar panels, conserving water, and riding bikes. However, both of these fields, separately and together, go much deeper than these simple examples.

The reusable bag is a familiar, simple example of Sustainable Design, and can be used to trace the many layers of the Sustainable Design Process. Reusable bags are one small way that consumers can minimize waste. How we identify with and use these bags as part of our everyday lives becomes a deeper design challenge.

Design as Visual

While a shopping bag’s basic purpose is to hold purchases, it is also a visual object for brands to advertise on and for consumers to identify with. One of the designer’s first challenges is to improve the image of reusable bags, as illustrated by the “I’m NOT a Plastic Bag” tote bag. Created by London fashion designer Anya Hindmarch in 2007, this bag transcended its utilitarian use to become a sophisticated object of desire that was quickly donned by celebrities around the world and became a fashion icon. Similar messages can be seen glamorized on products across the spectrum. “One less”, “I am not a ...”, “Reduce, Reuse, Recycle” and other slogans are carefully crafted onto fashionable everyday objects. We spend just seconds making most of our purchasing decisions, many of which are based on looks. Making branding and visual messaging around sustainability is important and familiar; however, these kinds of Sustainable Design do little to challenge the existing paradigm of consumerism and consumption, so ultimately their impact is limited.

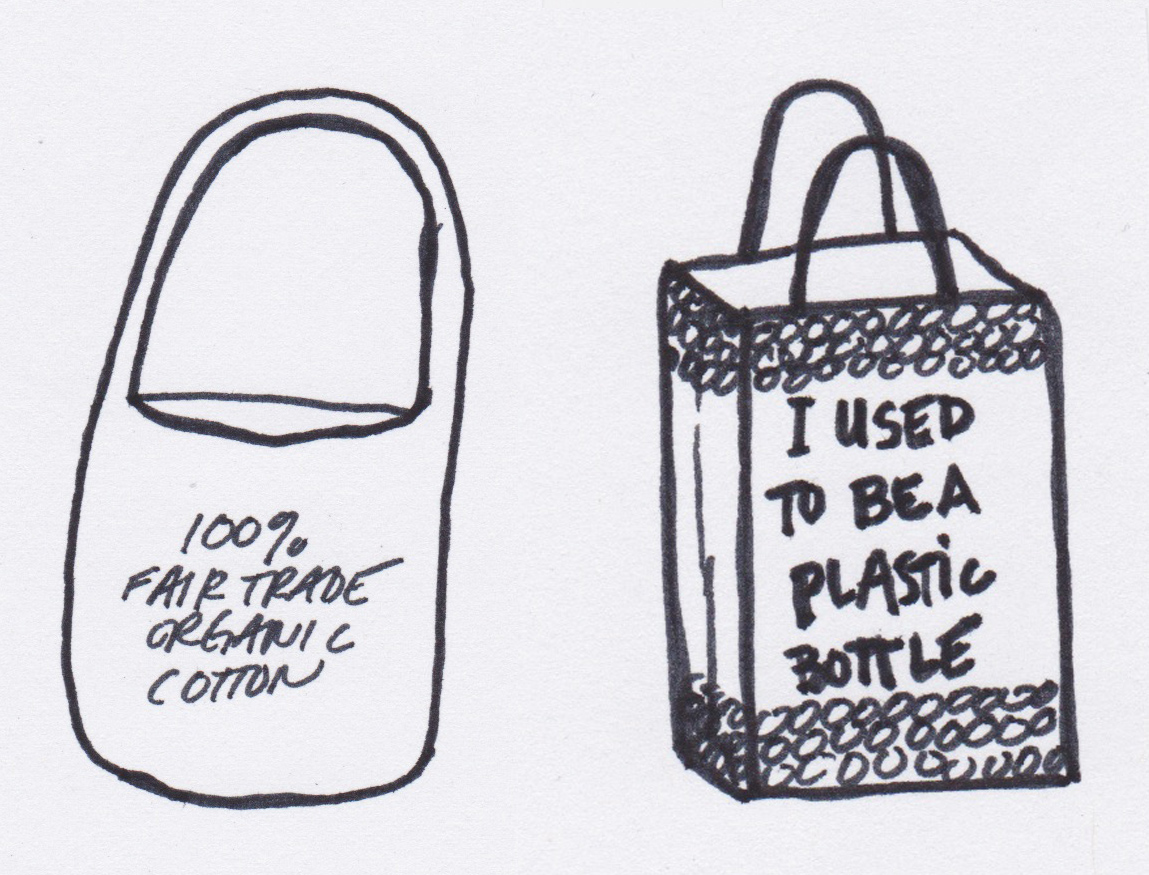

Design as Material

Beyond the message, designers think about the materials that go into making products. With the bag, the message is now about both reusability, and being made in a more environmentally friendly way. “I used to be a plastic bottle”, “100% Fair Trade Organic Cotton”, “Reused tires” are all statements printed on non-traditional materials transformed into bags.

In Cradle to Cradle: Remaking the Way We Make Things, Michael Braungart and William McDonough argue that we need to remake our products in a cyclical system that produces zero waste. What is made should be able to go back to the earth, be recycled, reused, or remade into something else. The designer and consumer should always think about how the end product can simultaneously be the start of its next incarnation. The idea of zero waste has led some designers to make products not only out of recycled materials, but also with an eye towards its next life. Examples include packaging grown from fungi, shoes recycled into playground equipment, and reusable shopping bags that become rugs, yoga mats, and aprons.

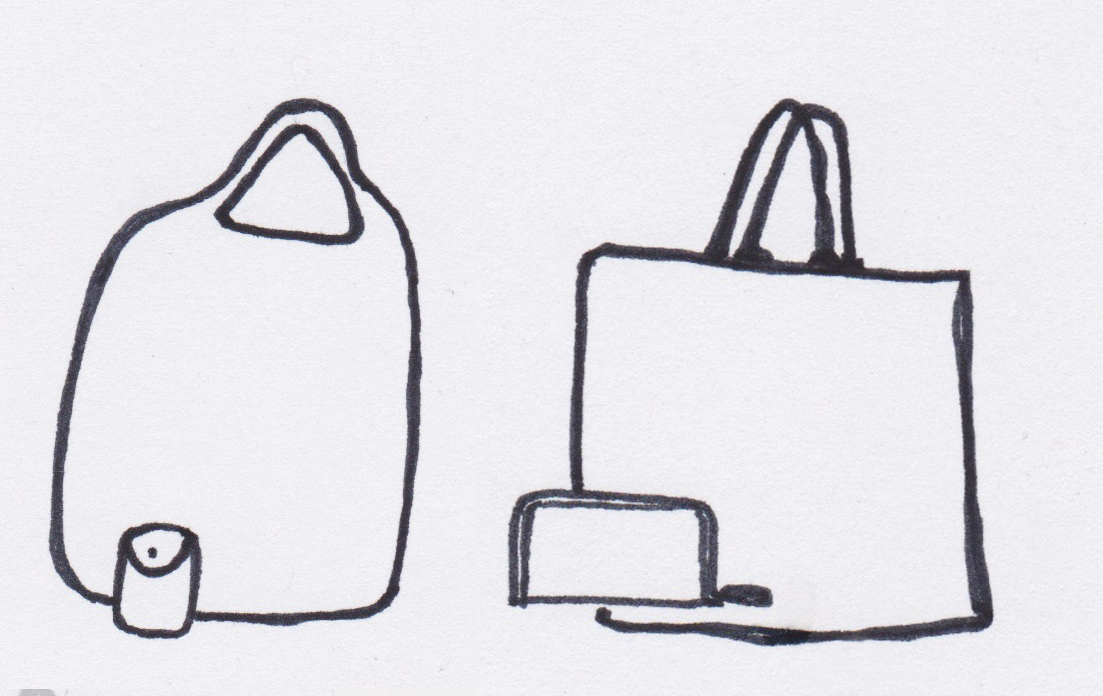

Design as Form

Even the most beautiful and environmentally friendly bag is only effective if it’s actually used. And while we might want to be seen with our fashionable totes, our actual habits and behaviors sometimes get in the way. We forget to bring our bags, or think that we can’t always carry them with us wherever we go. Here, Design Thinking is employed to take into account empathy for the user (how to help remember), creativity (new forms), and rationality (how to fit in your life realistically). From this we can see a whole line of bags designed to fit how we function in our lives. Bags that fold up into clutches, scrunch down into pouches, can easily fit in our backpacks or be clipped to our belts, and so on. These bags are designed with the user’s interactions in mind.

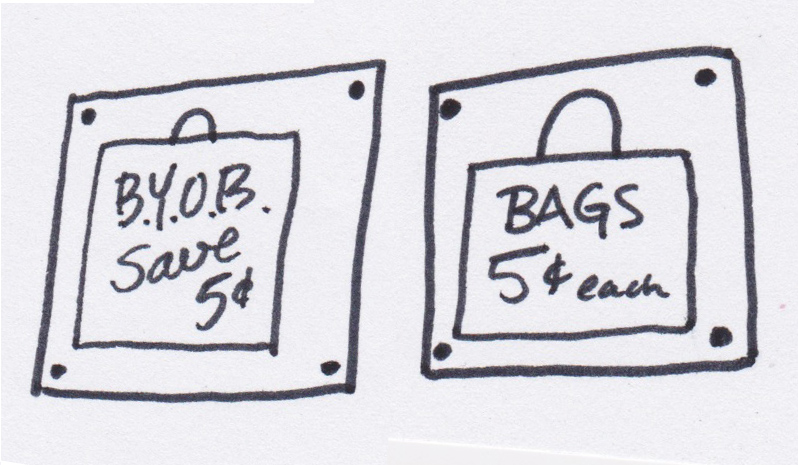

Design as Policy

Design does not stop at the immediate user. We can go another step and look at how our behaviors fit within the system the bag belongs to (the store). Consider the cost presentation of bags. Prior to many governments outright banning plastic and free single use bags, it was a given that when you went to the store you got one for free. Some stores would offer an incentive for bringing your own bag, perhaps a 5 cent discount. While this was meant to encourage you to bring your own bags, the actual saving was not a large enough incentive to follow through. However, when stores began to charge 5 cents for a bag, suddenly behaviors changed. Arguably there isn’t much difference in saving 5 cents versus being charged 5 cents, but the simple change in mentality was enough to alter how people remembered to bring reusable bags to the store. For example, IKEA was one of the first major retailers to implement a bag charge. The retailer cut bag use by more than 50% in one year simply by charging for bags instead of providing a discount. IKEA has since gone on to do away with single use bags entirely, replacing them with their blue “bag for life”.

Design as System

When we start to apply systems thinking to Sustainable Design, we can examine much larger complex questions. Instead of only thinking about what our bag looks like, is made out of, and how it’s used, we can start to think about why we even need a bag in the first place. We use bags because we need to carry goods from the store. But what if we didn’t go to the store? If we go even further, what if the food comes directly to us, not via a grocer, but straight from the farm in a box that gets sent back and forth each week? This is exactly how consumers choose to get food delivered to them through Community Supported Agriculture (CSA) services. At this level, we’re not just thinking about the simple “I’m not a plastic bag” bag, but also about how our actions relate to food production, consumption, distribution, labor, and social justice. Out here, at this level, is where Sustainable Design can really employ its power. Combining the visual, the material, and the interaction, design influences us to rethink the ways in which a multitude of systems interact with one another.

Just as the issues of the climate crisis are vast and complex, Sustainable Design does not just provide one simple answer. The reusable bag is one small example of how to explore the idea of Sustainable Design – from the purely visual, to the pre- and post-consumer materials, to user experience, to behaviors and habits, and finally to the larger systems that cause us to need a bag in the first place. Thinking about Sustainable Design, these ideas can be scaled upward and outward and be interwoven to solve complex issues in transportation, architecture, education, health care, ecology and many other areas. Designers play a crucial and necessary role in reshaping how we see, create, and interact with the world around us.

Sources:

Braungart, Michael and McDonough, William. Cradle to Cradle: Remaking the Way We Make Things. North Point Press, 2002.

Burros, Marian. “Just the Thing to Carry Your Conscience In”. The New York Times. 18 July, 2007.

Cross, Nigel. Design Thinking: Understanding How Designers Think and Work. Berg, 2011.

“Design Thinking… What is that?” Fast Company, n.p. 20 March, 2006. http://www.fastcompany.com/919258/design-thinking-what.

“IKEA to Phase Out Plastic Bags in U.S.”, GreenBiz, n.p. 2 April, 2008. http://www.greenbiz.com/news/2008/04/02/ikea-phase-out-plastic-bags-us.

“I’m not a plastic bag”, We Are What We Do, n.p., n.d., http://wearewhatwedo.org/portfolio/im-not-a-plastic-bag/.

Case Study: Samuel Mockbee: Learning and the Rural Studio

John Blewitt

Sanders/Dudley House

Sawyerville, AL

1999–2001 2nd Year Project

With the assistance of the Hale County Department of Human Resources, the Rural Studio selected the Sanders-Dudley family as clients for a new home. The family has six children. The Sanders-Dudley house encompasses 1500 sq.ft. and has 3 bedrooms, 2 bathrooms, a kitchen-family room, a den and a dining room. The family gathering spaces open onto a central courtyard which is bathed in light at sunrise and sunset. The house is designed to accommodate the many different needs of such a large family, attempting to give children and parents adequate private space, but at the same time creating rooms that foster family interaction. Great consideration was given to daily activities such as preparation for school so that the house might ease the hectic task of raising six children. The material pallet employs rammed-earth for all exterior walls, a steel roof structure, metal studs and sheet-rock on the interior, and an abundance of glass and transparent sheets of poly-carbonate in clerestory windows above eight feet and window-walls surrounding the courtyard.

Rammed earth construction, chosen for the Sanders-Dudley house, is a building technique in which a cement-soil mixture is compacted into forms to create load-bearing walls that harden into what is essentially man-made, engineered rock. Rammed earth was chosen for the construction method because of its durability, its natural resistance to fire and tornado and its sense of permanence and security. The students have researched the rammed earth method through books and government publications, consultation with experienced contractors and extensive tests and mock-ups. Except for some experimental housing built in the 1930s near Birmingham, AL, this is the first house in the Southeast to use this method of construction.

Source: www.cadc.auburn.edu/soa/rural-studio/projects_sandersdudley.htm (URL no longer valid). For more information on Samuel Mockbee's work go to www.ruralstudio.org/

Further information:

Samuel Mockbee's website: http://samuelmockbee.net/

Recommended Routledge Books

Supplementary Reading

Textbook

Research

Professional

Reference

Free Journal Articles

- Karuppannan, Sadasivam and Alpana Sivam, 2011, ‘Social sustainability and neighbourhood design: an investigation of residents’ satisfaction in Delhi’, Local Environment 16(9), pp 849-870

- http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/13549839.2011.607159

Blogs and Websites

- We Are What We Do is a non-profit behavior change company. They strive to use Design as a means to create behaviour change around social and environmental issues.

We Are What We Do http://wearewhatwedo.org

- This is the blog of Tim Brown of IDEO, who presents ideas in how Design Thinking is implemented around the world in many aspects of our lives.

Design Thinking at IDEO http://designthinking.ideo.com

- A design firm headquartered in both Berkeley, CA and Paris, France that focuses on Sustainable Deign.

Celery Design http://www.celerydesign.com/studio

- A series of online videos that use the power of storytelling and simple graphics to educate people on some of the complex issues of climate change.

The Story of Stuff http://storyofstuff.org/

- The design firm that actually created the animations for The Story of Stuff. They use the power of storytelling to create positive change. They are best known for “The Meatrix”.

Free Range Studios http://freerange.com/

- A TED talk by Janine Benyus

Biomimicry in action www.ted.com/talks/janine_benyus_biomimicry_in_action?language=en