Parent stories

Listen to what other parents have to say about life with more than one language

On this page you will find sound bites with excerpts from some of my interviews with parents who have current or past experience of raising children with more than one language.

Anthony from Sierra Leone

Anthony himself grew up with several languages (listen to his story on the Children’s page). Now he is bringing up his daughter in English and Swedish in Sweden.

Listen to Anthony's experiences

Loretta from London

Loretta grew up in London with Italian and English (listen to her story on the Children’s page). Here she tells about a later stage in life, bringing up children to speak English and Swedish in Sweden.

Listen to Loretta's experiences

David from Scotland

On the Children’s page, David tells the story of his own upbringing with Scots and English. As an adult he added Spanish, Catalan and Galician to the equation and here he tells of his experiences.

Listen to David's experiences

Jérôme-Frédéric Josserand and Celine Rocher-Hahlin

This is an informal chat in French between Celine and Jérôme, both lecturers in French at Dalarna University in Sweden. They have both raised children in Sweden with Swedish partners.

Listen to their experiences

Clare from Canada

Clare tells about her experiences as an English-speaker from Canada, raising a son with a Swedish father in Sweden. The family has passed through different phases of language usage.

Listen to Clare's experiences

More stories for parents

Here you can hear people talking about their experiences of speaking a minority language in Christchurch, New Zealand. If you would like to share your own experiences of raising children speaking more than one language, please contact us via our Facebook page. We’d love to hear from you!

Chinese mother 1

Chinese mother 1 - parent quote 1

I brought many Chinese books to New Zealand actually, and used some books to teach my older son, but my husband did not agree. Children are smart. When my son saw his father’s reaction, he told me: “Mum, I don’t want to learn Chinese.” Then I asked him to learn five Chinese characters each day, and write down each character once. You know, it’s actually very easy, I mean it doesn’t take the child too much time, and after that he could go to have fun. However, my husband thought that I was forcing my child, and he believed our child won’t go back to China, so it is unnecessary to learn Chinese here. Then I thought, what a good chance to let my child learn two languages! Two years later, my son knew some simple Chinese characters, but without the good environment to practise, it’s difficult for him to know many Chinese characters.

Chinese mother 1 - parent quote 2

Now it seems it is a trend that people can speak multiple languages. What I mainly consider is [my daughter’s] future. I don’t know how this society will develop, but I guess the skills and knowledge will still be needed in the future. If my daughter can speak more than one language, she can not only benefit from it, but she can also help others. For example, my daughter met an elderly lady who asked her for directions, the lady spoke Chinese to my daughter as my daughter looks exactly like a Chinese person. However, my daughter’s Chinese was not good enough to help her, so she called me to ask me to help that lady. Then the lady said that my daughter is a “banana person”, as her skin is yellow, but inside of her, it’s white.

Q: Do you think “banana person” is a positive or negative expression?

I don’t know. Maybe that elderly lady thought it was a pity, as many Chinese people who were born overseas forget their culture. Maybe she was sad about it, she did not mean to judge. I think I am a Chinese no matter where I go or live.

Chinese mother 1 - parent quote 3

I think we should not forget who we are and where we came from. No matter what extra languages we speak, we cannot forget our heritage language and our original identity.

Chinese mother 2

Chinese mother 2 - parent quote 1

As a mother, I gave her life. I was determined to teach my child to speak Chinese partly for my benefit, as it would facilitate our emotional communication and daily life communication. Besides, I believe it will help her future life as well.

Chinese mother 2 - parent quote 2

I always respect my daughter, and in fact she decided to learn Chinese when she was five. At that time, I went to China quite often to visit my parents. I have a good friend whose daughter is one year older than mine. Every time when I went back to China, she would pick us up, and drive us to visit many places and have fun. My friend’s daughter was around six at that time, and studied in a local kindergarten. Once, my friend picked us up to hang out, my friend and I sat in the front seats, and our daughters sat in the back seats. My friend’s daughter started to read out when she saw the shopping malls’ names or the billboard. Then my daughter asked her “Why do you know all of these? Why can’t I read them out?” My friend’s daughter answered “I learned them”, then my daughter said to herself “I learned Chinese in New Zealand too, but I don’t know the characters at all”. So my daughter said to me “Mum, I need to come to China to learn Chinese!” I asked her whether she decided or not, she said “yes”, then I respected her. So when she was six, I took her to China to learn Chinese. I believe my child is so endurable and insistent, and I won’t forget that experience in my rest of my life. I also believe as long as my daughter has made the decision, she will achieve it.

Chinese mother 2 - parent quote 3

Sometimes I feel really sad, as I heard some people saying “Learning Chinese is not important any more, as we live in an English society”. I think it is a big loss for Chinese who are unable to speak Chinese. I also heard some parents saying: “Do not speak two languages with your children, they will feel confused, and speak slowly.” I just want to say this kind of thought is really unwise. I can’t say everyone has the same situation, but take my close friends and my children for example, bilingual education won’t confuse children at all! My daughter knew how to pronounce “grandma” in Chinese when she was seven months old, and knew Chinese pronunciation of “dad” when she was around eight months old. She could speak many words when she was 11 months old.

Dutch daughter 1

Dutch daughter 1 - parent quote 1

Q: What would you advise to parents when they get children: raising them bilingually or not? And if bilingually, how can one do that most successfully?

A: Well, I would certainly say raise bilingually, because for me… it had no negatives. It is only positive. And I love it. And yes, when you are a child you learn quickly.

And… how. I don’t quite know. I would say, yes most of all speak to them in that language. especially when they are young, that they most hear the language. And yes, perhaps… It is difficult as a child I think… my sister had a lot of problems with it: “What’s the use? I live in New Zealand after all?” So if you can get it across to them that it is important and something great to have, than they will be more inclined to learn two languages. While if they think “What is the point? It’s no use”, then probably not.

Dutch Mother 1

Dutch mother 1 - parent quote 1

When they [her children] have been in Belgium or the Netherlands, well then they rattle on in Dutch. Then it suddenly… then it surfaces and they are really fluent. With errors of course. You always hear that they are not really native speakers. They are obviously English speakers, but fluent [in Dutch]. After those two weeks.

Dutch mother 1 - parent quote 2

When my eldest daughter was born and that was not in the Netherlands but in Italy, I spoke only Dutch to her. So she was my Dutch-speaking eldest daughter. Then two years later we had a boy and until he was two I spoke Dutch with him and my husband English. But he read Dutch books aloud as well: ‘Jip en Janneke’ [a classic Dutch book] for instance… and this oldest boy told his father: “You’ve got a bad voice for Dutch Dad!” And he was not allowed to speak Dutch any longer.

And that was very difficult because from then on we switched more and more to English. And by the time my third child appeared the home language had become English. So though we had intended to bring up the children with Mum: Dutch, Dad: English… by the time my youngest daughter was born it did not happen at all. It was purely English. She spoke English to siblings, to me, to her father. Dutch was not used.

Dutch mother 1 - parent quote 3

When she was four we went for quite some time to Belgium and there she heard people speak Dutch daily, and she spoke it herself with granny and aunt and uncle. With them she could speak Dutch. So there Dutch appeared again.

Then we tried to keep that up when we came back home, but within a week it was all English again. There were no Dutch friends in New Zealand. There was no input from outside the family. Nothing at all. The only input was when we went back to Belgium.

Dutch mother 1 - parent quote 4

Family was incredibly important. Not only for speaking with when we are there but also because I have a wonderful sister who sends books. My mother always sent books, my sister always sent books. And not only paper books but when the older children were little we had those little cassette tapes… so endless listening to fairy tale series. And later we had videos. A huge amount in Dutch. And later we had DVDs and also computer games. So the children had a large amount of computer games in Dutch.

Dutch mother 1 - parent quote 5

I regret we did not continue to speak Dutch at home. Today my eldest son, who put a stop to it all in the family that is also his biggest regret, that we did not continue to speak Dutch. So that is something to recommend to other people. If you don’t speak Dutch because one parent does not speak the language for instance or because the children put their foot down and refuse… you can always bring Dutch in through the back door. So read aloud. Read aloud all the time. Read books, give books to the children to read. Give films. And when you watch an English film, do so with Dutch subtitles. So they can learn it that way. Nowadays there is so much… computer games. The internet.

Dutch mother 1 - parent quote 6

Parents who come here… they see this environment and then try as fast as they can… “Yes we want to be New Zealanders, we must speak English… and our children must speak with a Kiwi accent” and our language drops away.

And you have children who refuse. Because they don’t want to be different from the other children at school. And it could be a reason to be unhappy… so the parents will say: “OK we will switch to English because we don’t want to disadvantage the children. They must not be unhappy at school because of being different.” So that is another reason why parents don’t transmit the language.

And yes, sometimes it is simply easier not to. Especially if one of the parents does not speak Dutch. So those are all valid reasons why the language is not passed on.

Q: Because sometimes people don’t even think about it. It is an automatic process.

Yes.

Q: Isn’t it. The children come home from school… they have done everything in English that day and even though you have spoken Dutch in the morning… they come home and continue in English. There are English friends and you cannot be impolite. So you have to speak English… the friends go home and you simply continue in English.

Yes exactly, it comes automatically.

French daughter 1

French daughter 1 – parent quote 1

I think for new parents, if they’re struggling with the idea of: “do I keep pushing for it or do I give it up?” I think you should push for it. Especially when they’re quite young because they don’t really know what they want [laughs]. I think that… I really appreciate growing up with French, and I would’ve preferred to have a little bit more nowadays, so I think they will appreciate it later on.

French daughter 1 – parent quote 2

[Talking about what advice she would give to parents of bilingual children] I think different forms of the language is quite good. You know like, have some books, and some films, and… it sort of becomes more of a language than some words or something you say here and there. Like it becomes more of a culture almost, if that makes sense? I guess it might depend on the child and what they lean towards. But I really leaned towards reading, I really liked that, so… especially for anxious children like me, if you find something they can feel confident and, you know, quite happy about doing then that’s good. If my main form of learning French had been around Alliance [Française] with lots of people and then I felt really anxious, or if I’d gone to France and everyone had been quite like: “Oh that’s wrong! You said that wrong!” then I would’ve really withdrawn and not felt comfortable speaking it and it probably would’ve got a lot worse I think. So I think feeling comfortable with the language is quite important, no matter what age.

French father 1

French father 1 - parent quote 1

Well, first of all, when they were very little, it had only been a few years since I left France and French was very important to me. So I think that with the eldest it was very natural for me to speak French to her when she was young. Now, it’s been a good number of years since I left France and I am so constantly immersed in the English language that this habit of speaking French has slowly faded over time. For a few years now I’ve tried to make myself speak French to them on a more regular basis because, on the one hand I think it’s important that they get to know their culture and their roots and, on the other hand, there’s the matter of communication with grandparents, cousins and so on. I’m conscious that they need a minimum of French for that communication to happen naturally.

French father 2

French father 2 - parent quote 1

Q: What influenced your decision to raise your children speaking French?

So we always spoke French at home and I don’t think we really thought about it [laughs]. For us of course it was just easier to speak French [the children’s mother is also French] and then instinctively we always thought that since we had suffered [laughs]… it’s true though! When you’re not bilingual from birth it’s harder. So it happened naturally and we don’t regret it. And the children are happy about it too, I think.

French father 2 - parent quote 2

[Talking about what other people think of his children’s bilingualism] Most people think it’s fantastic, because we know a few couples in our situation who did not do the same as us – they preferred to speak English – so we feel a bit of regret from them, or a bit of longing [for our situation]. Because it’s true that having kept up this practice helps them [the children] a lot. Even if they speak with a bit of an accent, or they haven’t learnt to write well in French, they confidently know that they can go to France on their own, no worries. They would be able to get by.

French father 2 - parent quote 3

Q: What advice would you give new parents about transmitting their native language if they are not native English speakers?

Well I think there are parents with regrets.

Q: Who regret not having spoken their own language with their children?

Yes, that’s right. Yesterday, for example, I was with a friend from Quebec, who has two sons. He was married to a New Zealander, and he didn’t speak much French to his second son, who was also here with us yesterday. But he is motivated: what’s interesting is that he’s so motivated. They’re just back from a trip to Quebec – they spent a few weeks there in June–July – and we could sense how much he wanted to try [to speak French], since he was so recently back from Quebec. He really wasn’t afraid to try. But the father, he didn’t say this yesterday but he’s often told me, that it’s a shame that he didn’t [speak more French with his son].

Q: And the son, do you think he also regrets not learning it [French]?

Yes, I think so. Yes.

German parents

German parents - parent quote 1

P2: [Talking about why they taught their children German] I guess the main reason is that we know that it’s good for their future and gives them more opportunities. It would be easier to not do it. English is much more natural to us. So sometimes we start a sentence in English and realise oops we should actually speak German.

P1: Yes we lack consistency.

German parents - parent quote 1

Q: What advice would you give other parents in your situation?

P1: Speak German more consistently. Perhaps only German at home.

P2: No maybe that’s not true. Maybe just the travel would be important, or the exposure to the language and the culture. If you have 5–6 weeks there is quite a lot of learning that happens at that time – that is happening naturally.

Korean daughter 1

Korean daughter 1 - parent quote 1

On the Korean school side, I think it’s not as important to someone like me living here. Because I don’t have to take any tests in Korean, and if I can speak it I think it’s OK. As long as I’m able to communicate with my parents. But then I feel like when I was put there [in Korean school] to learn in that way, instead of actually using it around Korean people, I learnt way less than I could have. I found that if I read Korean manga or just something enjoyable, I learnt way more out of it. And even watching drama… yeah, I learnt way more from it. Especially for language: applying it is the most important.

Q: So if someone like you, born in New Zealand Korean, they want to maintain their Korean language, what is the best way, do you think?

Having their parents speaking it to them, even if they don’t understand it. I think that’s the best way to do it. You just pick up on it, randomly.

Q: Especially when you are motivated.

Yeah!

Korean daughter 1 - parent quote 2

[Talking about advice for other Korean parents] I’d say that you shouldn’t abuse one language. You should evenly share out two languages… or even just focus on your own language. It wouldn’t affect their education, that’s what I believe. Because they’d end up learning English outside, at school, and then when they come back home, like I said, the amount of parent time you’d speak your own language is very short. So it wouldn’t completely fade away your English language ability.

Korean mother 1

Korean mother 1 - parent quote 1

I believe that language is related to emotions and these [language and emotions] are also related to culture. So I told them they should know the Korean language because they are Koreans. Speaking the Korean language doesn’t simply mean being able to speak the language, it means that those three factors [language, emotions and culture] are related to each other like chains. So I thought if they were not able to speak the Korean language there would be big gaps between us, I believed that. That was why I encouraged my children to use the Korean language at home and luckily our home language gradually changed to Korean even though we sometimes spoke ‘Konglish [Korean-English]’.

Korean mother 1 - parent quote 2

Bilingual children don’t have only one perspective. They can have multiple perspectives for dealing with things. Understanding languages, even if they are not fully understood, makes it easier to become familiar with a new culture. And whatever they [bilingual children] study or work, they can see not only one side but also the other side of the culture. For example, talking about colours, there are different ways of describing colours in Eastern and Western cultures. So I believe being bilingual is helpful for their schooling. My daughter may not realise this. Because it has been natural for her to be exposed to a bilingual environment all the time at home and at school.

Korean mother 1 - parent quote 3

I disagree with some Korean parents who speak English at home to their children from birth. I have met some [Korean parents] who did that [spoke English at home] and they regretted in the end.

Q: Why did they regret it?

Because the parents were Korean and they had many chances to interact with other Koreans. But their children couldn’t interact with other Korean children to maintain friendships because their children couldn’t speak the Korean language. They regretted a lot.

Q: It seemed parents kept interacting with other Koreans even though they wanted to raise their children as primarily English speakers.

Parent materials

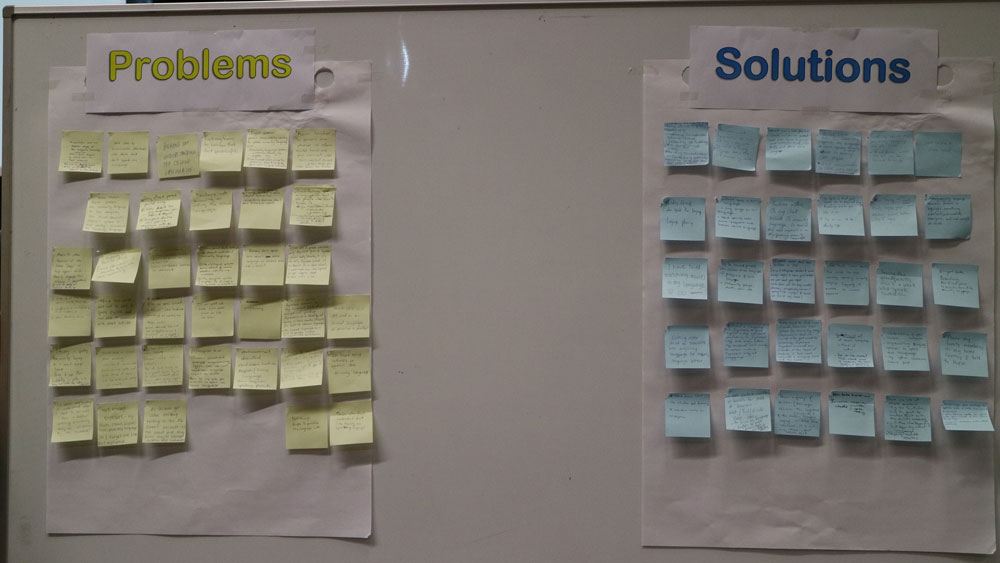

Problems experienced by parents and carers in raising children bilingually

At a parent and carer workshop on raising children bilingually, I asked participants to share problems they have experienced on sticky notes and pass them to the front.

Literacy

- How can I teach my children Chinese grammar? I send them to Chinese Saturday school because we only speak and talk Chinese at home, but what can I do about reading and writing?

One parent/grandparent doesn’t speak the minority language

- I want my husband to understand when I speak to our kids.

- In my family, we parents don’t speak each other’s native language. My husband is Korean and I am Chinese.

- As an English-speaking parent, I desperately want to speak the minority language but minority language speakers switch constantly to English, or exclude me from minority language events as they don’t want English influence.

- I am not a native Japanese speaker, so my husband feels it is unnatural speaking Japanese as a family at home – this makes it hard for him to choose Japanese. As I speak Japanese as a second language I often struggle with my own confidence.

- My in-laws are “afraid” of or against the minority language, and would rather I just spoke the majority language with our child.

- Only one parent speaks the minority language, French, and that is the father. No other families nearby speak the language. It is easier to speak English than French with the children.

- My partner doesn’t speak my language, so I tend to speak in English most of the time.

- I am a grandmother. My son’s wife is Dutch, and they are speaking Dutch to their child. I don’t speak Dutch, so how can I support a child growing up in New Zealand with a Dutch-speaking mother?

Politeness/embarrassment

- As a bilingual speaker, I am afraid of native speakers noticing my mistakes.

- My daughter is at primary school and her friends and everything is in English. I feel like I can’t speak our language in front of others. I am afraid that my kids may feel ashamed to speak their home language.

- How can I use Te reo Māori confidently in public in a way that makes the learners comfortable?

- We are reluctant to speak our home language in front of others. There is a need for education of society to let this become more normal.

- People within earshot who don’t understand my language don’t like hearing me speaking the language.

Child answers/might answer in the wrong language

- My child understands the minority language but replies in English. The child prefers songs in English.

- My daughter replies to me in English. Do I insist on her replying in the minority language?

- Even though mom speaks the minority language to her daughter, the child doesn’t speak it and always answers in the majority language.

- As my children get older, they have started to avoid talking to the parent who speaks the minority language, because it’s too hard and they know they’re allowed to speak English to the other parent.

- I am afraid of my child hearing me as a parent speaking English to other children, afraid he will start speaking English with me instead of the minority language.

- My children only want to speak English.

- 168 languages are spoken in NZ but intergenerational transmission has been interrupted. How can I motivate my child to want to know and use my language?

I am isolated with my language

- I do not get enough exposure, e.g., books, shows, friends that speak my language. So I forget and I am not motivated to use it with my child.

- We would need access to other families at the same stage to help support children to use the family language. Otherwise the language is potentially going to be only an isolated thing.

- There are not a lot of options available. My child goes to the only Japanese school in town every Saturday. If he doesn’t like that school, I won’t have any other option to get support from. It also costs a lot.

- The only parent who was fluent in the minority language passed away.

- My husband does not understand the minority language. I am not able to communicate effectively with others who don’t speak my language, so my child never hears it being used fluently.

- How can I create a Chinese-speaking environment for my children?

- Teachers do not know or use the minority language, so the child does not hear the language for a large part of the day.

- I am afraid that my child will not be able to speak English and will not able to communicate with people outside our home.

- My kids do not like to learn our home language. We don’t have many materials and we are not good teachers.

- There are not enough people nearby to practise the language with.

Preparing for school/early childhood education

- How do I make sure my son can explain himself in day care? When he needs something he mostly uses Persian words! When other kids talk with him in English, he can’t communicate well in English and I am not sure if that affects his self-esteem. He just turned two.

- How can I help my child to get used to a second language as quickly as possible?

Motivating reluctant children to speak a home language

Raising Children Bilingually

The participants were invited to share their ideas for increasing the input children get in the minority language, and increasing the children’s need to use the language.

Here are a selection of the suggestions shared by participants about how to create opportunities for children to have more language input and interaction

At home

- Use software to increase language input: interactive games/apps in target language on iPhones, iPads, computers

- Smartphone, TV in home language

- Switch electronic devices to the target language

- Interactive toys that speak the minority language

Online interaction with native speakers (relatives or friends)

- Video conference (Skype) with monolingual family members

- Skype time with relatives and other kids in the other country

- Bring the iPad with Skype conversation into the Lego box to join the children’s play

Reading books, magazines or other materials

- Reading books in minority language

- Magazine subscriptions (paper or online)

- Audio books – buy or borrow from libraries; swap with other families

- Comic books written in the minority language, they will be motivated to know how to read

- Carer reading story books and recasting it into the minority language

- Book club in the minority language

Community

- Arrange minority language teaching classes with the help of some other families with the same language

- Send the child to community language school if it exists

- Alliance Française/Confucius/Goethe institute

- Parent can visit the class at school

- Private language lessons appropriate for their ages

- Access to other children of the same culture – build a network of friends in minority language

- Play groups with minority languages (coffee together for carers!)

- Community groups and cultural community based activities

- Community church

- Games – play groups in home language

- Preparing a short speech or song to be presented in the community gatherings

- Join the Vietnamese events – that improves both the language and culture knowledge

- Making gatherings and functions for those people who speak same language: e.g., independence celebrations, potluck dinner,

- Share kai – traditional/cultural food with other speakers of the minority language

- Language weeks celebrated

Contact with the old country

- Get children to write to monolinguals (pen/email pals, birthday cards to family members in home country)

- Sending to parents who speak the minority language to stay there for a while, or home stay in minority language country or someone’s place in NZ

At home (notice the varying levels of ambition here, and that some families have more than one parent or carer who speaks the minority language, while others may be alone in their language with a partner who doesn’t speak their language)

- Only speak native language at home. Strict rule!

- Always speak minority language to anyone who speaks it, even outside home. Don’t worry about the English!

- Let children hear the language all the time. Children automatically learn and understand the language spoken to them.

- Dinner time table talk in Maori/Samoan only learn new phrases for this time/bath time/bed time

- Getting majority language speaking parent to participate in minority language learning

- Making it a game!

- A day of the week or time of the day when only minority language spoken

- Create environment for the language: make a language island and speak the language at home

- Encourage children to chat at home in first language and find friends to interact with who also have the first language

- Have a party with minority language theme

- Getting mum and dad to speak Samoan to the kids

- We as parents speaking our languages to children

- Asking grandparents to speak only their language when we are around them

- Ask other members of the family to encourage the child to speak mother language

- Set aside a special time for an activity in L2 each day (something fun, e.g., making craft, story time/singing nursery rhymes) keeps it current and fun for kids

- Children have to speak minority language when they ask for buy things they want

- Have a language day at home where you only speak one language, e.g., during dinner or games

- Strategies: In early childhood, have puppets to role play

- Enrol them in a sports club that speaks minority language and buy them video games of minority languages

- Labels around the house to help children learn words

- Karakia (prayers) written and at the dinner table

- Celebrating special events for them

- Participating minority language culture/game

- Join cultural club in minority language

- Learn poems, songs, and rhymes

- Use the minority language: greetings, music, dancing, food, dressing up

- Make a time for the language hour at home (every Sunday morning or so)

- Board games with language, can have other language speakers and they explain with certain idioms

- Word games (I Spy, charades, etc.) with prizes

- Cultural classics and amazing moments in history, as told in target language

- Creative play – using words

Travelling to where the target language is spoken

- Travelling through South America to immerse in Spanish

- Send him to my mum to only speak Swedish

- To make friends with the same language children

- Back to our country for a while

- Holiday back to China to enrol into a local school for a month

- Shared holidays with other families

- Going camping together

School activities and school strategies to motivate students

- Pre-school or kindergarten in an international setting

- School wide speech competition presentation – poetry or short story bilingually per term

- Preparing for events at school where the kids are expected to use their home languages

- A language week of their own culture within school setting

- Find (or start) a local pre-school that teaches the language and culture

- Sharing your culture language with teachers and children we want to learn more

- Have language competition days

- Involve school/pre-school by assisting child to share their language with other kids using posters, etc. (e.g., body parts labelled)

- sharing things about their culture with the older kids in school

- parents participating in school activities and kids taking roles

- Schooling: language cultural activities, i.e., Kapahaka

Materials for target language (CDs, videos, music, YouTube, radio)

- Music in native language

- Drama/cartoons/films in native language

- Web radio station – cheap and efficient can have it on all day

- Nursery rhymes

- Watch TV programs: TV on demand

- Digital music, movies (DVDs in Spanish), CDs in the car

- Picnics and playing music and dancing

- Maori television

- YouTube – songs, Action songs

- Waiata CDs

- Friends/family send videos of them

- Songs are fabulous for children language development

- Kids TV show: Find Samoan and Maori language programmes to watch

- Video that children like and watch again and again

- Show videos of other countries – they will know that there are other people that speak other languages to learn a minority language

- Stories, songs, with gaps that the children fill

- Watch video clips with them and strategically ask questions

- Watch music videos and listening to music in that language

- Encourage kids to learn nursery rhymes/songs from minority culture and play CDs so they can sing along

Strategies for motivating children (these won’t all suit all parenting styles and beliefs)

- Encourage them to play and communicate with their peers

- Encourage children to speak/learn own language

- Pretend not to speak language – child helps parent

- School teachers can encourage children to learn their language

- Praise out loud especially for younger children, they are happy when we praise them

- Letting child choose a movie or a game in minority language for a Friday family night treat

- Using the language positively and not for correction – make the language fun!

- Showing the benefits opportunity of being bilingual, e.g., business, travel, sports

- Having more input at home, invite minority language speakers to come and visit

- Pull and not push them towards the minority language

- Make them proud of being bilingual, show that it’s special that they have access to things non-speakers don’t

- Build the self-esteem of the child

- Lots of trips back home at least once a year

- Reward children when they use the minority language

- Appeal to heritage/love of family/ancestors’ identity

- Make them feel speaking a second language is special and important

- Give them a chance to use it and feel like it is important

- Being responsive in expressing and hearing minority language spoken

- Introduce our culture, like festivals, rituals, mysteries, stories to our children as early as possible, so they have attachment with their culture through the language

- Support their interests, e.g., baseball with children who speak the minority language

- Bribe them

- Make your culture more fun to them

- Build interest in some areas, for example, games in some areas of interest and learn language from there: Chinese chess for example

- Fun things, e.g., Japanese animation – kids love them

- Only respond to the child when the child speaks in the minority language

- Stickers – use for special acknowledgement

- Satisfying for my son when he knows the words to sing along!

- Recasting what they say in English into the minority language is better than pretending not to understand what they say

- Helping teachers to learn basics of children’s home language

- Treats for children when they speak the minority language

- Dinner table language – “Get the food”, etc. – use minority language

- Having a family outing where we only speak the minority language

- Cooking together and recipes

- Nanny/au pair who only speaks French

Starting school

Download Starting schoolImage |

Home language |

School language |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

I want to

|

|

|

|

Please help me to

|

|

|

|

Yes |

|

|

|

Organising a workshop on raising children with two languages

The workshop has three primary aims:

- To gather those parents, teachers and others in the local community who are concerned with children growing up with two languages in the hope that they will get to know each other for a mutual exchange of experiences and tips.

- To establish contact with those who represent the local authorities and schools in questions concerning the position of pupils who have home languages and who may require support in the majority language.

- To develop ideas together to support children’s development in both languages and possibly to make the initial contacts necessary to start minority language groups where children can meet others with the same minority language and develop their language (for example, toddlers’ group, play-group or Saturday school).

The workshop is designed to fit into an evening, with the option of getting together for a follow-up evening if there is enough interest. A possible arrangement is the following:

Have a number of pages prepared with room for eight to ten names on each. The papers should be labelled with a topic, for example:

- How can we optimise our children's linguistic development?

- How can we help our children to appreciate both their cultures?

- How can migrant parents improve their knowledge of the majority language?

- How can we get the most out of our family’s stay in this country?

- How can we support our children’s schoolwork in the majority language if we don’t speak it well?

- How can we make the most of an intercultural and/or mixed language marriage?

Select topics on whatever suits the participants’ interests. As people arrive have them choose which subject they want to discuss and write their name on one of the papers. Anybody wanting to be in the same group as a friend should write their name on the same piece of paper. Give each participant a name tag they can write their name on and pin or stick on their chest. They can also indicate on the name tag whether they are a parent, teacher or whatever.

7:00 |

People arrive, register (so they can be informed about further meetings and groups which are set up), choose a topic of interest for group discussion, pay the admission fee if there is one, and settle down. |

7:15 |

Introduction and keynote speaker with questions from the floor. Your speaker should be someone who can speak knowledgeably about bilingualism, intercultural relationships, children’s language acquisition and/or second language learning. |

8:00 |

Getting into groups according to the chosen topic. Each group has a leader assigned by the organiser. If possible, refreshments can be served while the participants are getting into their groups, so they can take their cup with them to the group. |

8:15 |

Groups discuss their topics. They can also brainstorm for ideas about their topic. Problems associated with the topics are taken up and maybe solutions are offered and experiences shared. The leaders are well prepared with questions but try to keep in the background of the discussion as much as possible. They should make sure everybody gets a say. The leaders take notes and/or make a mind-map of any brainstorming activities. If all or some of the group want to meet again to set up a regular activity, for example, a Spanish language play-group, a French-speaking fathers’ club or whatever, this can be arranged. A contact person should be nominated, so other participants can get in touch |

9:00 |

All participants reassemble. Leaders report on each group’s discussion, giving information about any follow-up activities the group participants want to plan. |

9:30 onwards |

Panel debate with keynote speaker, representative of the establishment and a couple of well-prepared parents. The subject of the debate could be ‘Growing up here with two languages’. Let each participant speak uninterrupted for, say, five minutes and then answer each other. Open the discussion to the floor when it seems appropriate. The discussion can then go on until all participants have said what they have on their minds. |

End |

The organiser might want to round off with a few words, and maybe suggest having another workshop in the future. |

The person organising the workshop needs to work out the following details:

- Think of people you would like to have come and speak at the workshop and make arrangements with them. You need a keynote speaker (maybe a researcher or teacher) and someone who can give a completely different kind of perspective for the final debate, maybe a local politician. Decide on your date with your speakers.

- Find a suitable location. While it is very difficult to estimate how many will come, try to find somewhere where everybody can sit together and listen to a speaker and then break up into groups for discussion and coffee.

- If you have to pay for the use of the room, or for speakers, you will have to charge admission. Make sure you don’t leave yourself out of pocket. There may be money available from some authority or other for this kind of activity.

- Recruit and prepare your leaders for the evening. Apart from being generally helpful, collecting admission fees, giving out name tags, serving coffee, etc., they will need to lead the group discussion and be prepared to report on it so all participants are informed about what all groups have discussed.

- Arrange tea or coffee and biscuits or whatever refreshments are appropriate in your country. You'll also need name tags, pens, paper and any kind of speaking aid such as a computer and/or a projector for your speakers if these things are not already in the room.

Family language policy

I have to say that I have been very strict… as soon as English was spoken in my house… I’d say: “Hé, hé, Dutch! Children, Dutch!” And that’s how I did it from the start. Yes. Yes, it was just a rule. At home we speak Dutch.

Dutch mother living in Christchurch

There are many ways for children to hear a minority language even in a very monolingual country like New Zealand. A good place to start is inside your own home. All families are unique, and have different language needs, constraints, special skills and opportunities. For example, in some families both parents share the same first minority language whereas in other families the parents are mixed language (this means each parent has a different first language). Some families immigrate permanently to New Zealand whereas others move here just for a short visit. You can think of how your family decides to use the language(s) you speak inside your own home as being your family’s ‘language practices’.

There are some common language practices that can help you work out what to do with your own family. The one person–one language (OPOL) method is when each parent speaks their own language to their children. This is a popular method that feels natural and easy for many parents, and means children can learn two minority languages if parents speak one each. It can be difficult for children to hear much of a minority language spoken by a parent who works long hours outside the home, however, and a parent who does not understand the minority language at all may sometimes feel left out of conversations. If both parents can speak the same minority language then the one language–one location (or Minority Language at Home, ML@H) method is another alternative. This is an especially good method to use in New Zealand since English is so dominant in the community that children will usually pick it up very quickly once they start school or pre-school, even if they have never heard it spoken at home.

In families where neither parent speaks a minority language the whole family could embark on a language-learning journey together, or perhaps the children could be looked after by a foreign au pair. There is no right or wrong way for children to grow up with a minority language and no one language that is better than another. Any exposure – even from a parent who is not completely fluent in the language – is better than none, and any language can enhance your child’s life!

Links to help you create your own family language policy

Minority language play-school

My first idea was to organise a French playgroup. At the time I had a lot of time and two children aged two and four, the third one came a bit later, we met once a week. We were about ten mothers, it was very nice and that’s how I created my first circle of friends because we would talk between ourselves and sometimes we’d say: “We must do an activity with the children” so we’d play a game with them. I thought it was important for them to hear other people speak French to show them that they weren’t the only ones with that oddity, that they shared that with other families.

French-speaking mother in New Zealand

The difference between the parent and children groups discussed above and this kind of group is that in a play-school setting the parents leave their children with a teacher or leader. For this reason, this kind of group is better suited to older pre-school children, around 3–6 years. In some countries children start school during this period, in which case another arrangement may be better. But assuming that a group of 3–6 year olds can be assembled, this can be a beneficial impetus to their use of the minority language. Of course, the success of this kind of arrangement lies almost entirely in the hands of the teacher. She (such teachers are usually women) will need to be very capable and inspire confidence in young children who do not know her and their parents. Many children, especially the younger ones, might refuse to be left. Many teachers are unwilling to have parents around, especially if only some of the children have their parents there. Nonetheless the children might need a settling-in period with a parent nearby, perhaps waiting in another room. Could the waiting parents arrange some amusement for themselves? What about playing Scrabble or doing crosswords together or having a reading circle to read books in the minority language and then discuss them? Such activities all play their part in keeping the parents’ language skills fresh.

Depending on the size and age of the group, the teacher may need a helper. In some groups, parents take it in turns to help the teacher, but this does not always work out too well in our experience, and it might be better to employ an assistant teacher. This kind of group is generally more expensive for parents unless local authorities can subsidise it. The teacher and assistant will usually need to be paid, as well as any rental to be paid for the use of a room and the cost of toys, equipment and stationery. This kind of play-school is often one afternoon a week, but if the parents’ budget can stretch to twice a week it is probably better from the children’s point of view.

Checklist for play-school organisers

The person organising needs to take care of the following matters:

- Funding: balance the books! How much do rent, equipment and teachers’ pay cost? Look into grants. How much should parents pay?

- Location: where can the play-school be (see above for suggestions)?

- Recruit a teacher. She needs to be a native speaker of the minority language, but she should be aware of the majority culture that most of the children have lived in all their lives. We once had a newly arrived American teacher in an English play-school in Sweden who tried to talk to the children about Star Trek, which had not been shown in their lifetimes on Swedish TV.

- Get together a group of children. There should probably be at least 12 children in the group. Any monolingual minority language children are a great asset in the group to help prevent the other children slipping into the majority language.

Planning

The idea was also shared by my husband… we both shared the conviction that bilingualism was an extraordinary thing we could give our children… When we decided to come and live here together I said the number one condition would be that we speak French at home.

French mother living in Christchurch with her Kiwi husband

Raising bilingual children requires some forethought and planning. Although speaking more than one language is very common in many parts of the world, it is unusual in countries where most people are monolingual English speakers (this means they only speak English). For example, in New Zealand, English is the ‘majority language’ due to the vast number of people who speak it. All other languages, including the indigenous Māori language, can be thought of as ‘minority languages’ in the New Zealand context.

Parents wanting to raise their children to speak one (or more) minority language(s) in addition to English should first discuss together what languages are important to them and why. It is helpful to talk together about the level of proficiency you hope your children can achieve in each language. For example, would you like your children to be able to use the language to talk to relatives on the phone? Or would you like them to be able to read and write in the language and, if so, to what level? Parents also need to think about what opportunities their children will have to hear the minority language(s), and how to find other speakers of the language(s) to turn to for support and encouragement when needed.

Planning these things in advance can help prevent disagreements and complications within the family later on. Language learning is a part of children’s development and parents can talk about it together just as they talk about other factors like their children’s manners, the clothes they wear, the schools they attend, and so on. Even if parents do not completely agree on the specific details of their children’s bilingual education, it is a very positive step if bilingualism is the topic of discussion and debate!

Read more about planning a family language policy in Growing Up with Two Languages.

Links to help you with planning

Parent and children group

The aim of this kind of group is to let minority language parents and pre-school children meet other children and parents with the same minority language to sing and play. Most groups meet once a week for about two hours, but other arrangements are possible. If there is a large minority language community, you may be able to meet more often. Not everyone can come every time.

What do you need?

The first priority is to investigate the matter of funding. There may be money and/or other help available from municipal authorities for this kind of group. Maybe you can also get help from the authorities to find somewhere to have the group’s meetings. Otherwise, finding a suitable location is the next problem. You will need either to borrow toys that are already there or to buy your own toys and store them in the room you use. Village halls and churches may have their own play-groups or play areas. Perhaps you can use such a room and borrow the toys without having to pay too much (or even for free). You will need access to toilets and changing facilities.

It can sometimes be difficult to get a group of parents and children together. Some tips for getting to know others with the same minority language are given under Networking in Growing Up with Two Languages. A workshop of the kind described in this site can be a good way to meet others in the same situation as you. You might consider advertising your play-group in local shops, religious meeting places, child care centres, clinics, etc., or in a local newspaper.

You may want to have some kind of snack during the group’s meeting. Parents can take it in turn to bring something along if that is what works best. You could have a duty roster where parents can sign up for particular weeks. They can then be responsible for arriving early and getting things ready, staying behind to clear up after the meeting is over as well as providing the snack. If the group is big, maybe two parents will be needed each time. The parent whose turn it is can also lead the group if any leadership seems necessary, although groups often work out a more or less set order of events. Some activities will need preparation.

Younger pre-school children are not always open to too much organising and may prefer just to play with the toys. If the parents get involved with their play they can make sure there is plenty of language happening. Songs, finger play and a simple story are often all the structured activity the under-3s can deal with. Arnberg (1987) gives an example of a possible order of events in this kind of play-group, involving planned free play with dolls or cars, active play with singing games, talking about a topic with pictures, snack, song and finger games, drawing or clay and a story, with each activity being allotted 15 to 20 minutes. Many of the activities might be beyond the youngest children. This is not a problem, since the parents are available to activate them in some other way. Perhaps the younger ones can play some more with the toys while the older children draw.

Things to bear in mind:

- There should probably be at least ten children in the group, to prevent it petering out too easily when somebody leaves or cannot come several times in a row.

- It is generally not a good idea to have a child come along with a majority language-speaking parent, unless they usually speak the minority language together. To avoid confusing things, the group’s meetings must be kept free of the majority language.

- The group is for the children’s benefit, not primarily a chance for the parents to chat. Left to themselves, children of this age are likely either to use the majority language or just to play quietly by themselves. The parents need to play and talk with the children to stimulate their use of the minority language.

Reference

Arnberg, L. (1987). Raising children bilingually: The pre-school years. Clevedon, UK: Multilingual Matters.

Bonding

I believe that language is related to emotions… Speaking the Korean language doesn’t simply mean to be able to speak the language, it means that the three factors [language, emotions and culture] are related to each other like chains. I thought if they [her children] were not able to speak the Korean language there would be big gaps between us.

Korean mother living in Christchurch

Many parents report feeling that they can properly bond with their children only when they are speaking their own first language with them. For parents in this situation, one advantage of raising children speaking a minority language at home is that the minority language may take on a special significance as it becomes associated with affection, comfort, love, and the intimacy or familiarity of home. Also, communicating with their children in a language in which they are highly proficient helps parents stay better involved in their children’s lives and interests outside the home as they grow older.

Speaking a minority language often also has positive implications for bonding with extended family, such as by ensuring that children can communicate with their cousins, aunts, uncles, or grandparents, for example. Parents who do not feel that the country they are living in is ‘home’, and who are able to travel back to visit their ‘home’ country with their children, also expose them to the rich culture, heritage, customs and rituals associated with the minority language. This is one important way for children to learn about, and be proud of, their heritage.

Another way for children to learn about their heritage is through literature, by either reading for themselves or being read to, in the minority language. Classic texts can influence beliefs and customs in culturally significant ways, which may be more deeply understood in the original language rather than via translation.

Links about bonding in your own language

Saturday school

Once children reach school age they do not have much spare time. They may have a series of activities ranging from football to ballet to chess, as well as all the time they spend with friends, playing computer games, and maybe even doing homework. An extra morning or afternoon at school might not stand very high on their list of things to do! Nonetheless, if the minority language community is large enough, it might be possible to get together a group of children to study the minority language. Many countries offer no provision for home language teaching of children who have a minority language at home, leaving it up to the parents whether their children become literate in the home language or not. Parents might find it easier to support their children’s literacy in the minority language together with other children.

Ideally, a qualified teacher should be enlisted to help, but if that is not possible, perhaps the parents can pool their resources. The parents need to get together and work out what they want from the Saturday school (which can equally well happen on another day), i.e., whether the children are aiming at going back to school in the home country or if it is enough for them to attain reasonable reading fluency to open the world of children’s literature in the minority language. Are the children to learn to write and spell in the minority language? There are materials and support available from home-schooling organisations and groups here and there. Otherwise, parents might contact schools and teachers in the home country for advice about materials and methods.

The practicalities of setting up a Saturday school are not any different from those for the other groups: funding should be looked into, but may not be available. A room needs to be found, although toys are not necessary. If there are only a few children involved they might be able to meet at each other’s homes. A teacher must be recruited if the parents are not to do the teaching. Books and writing materials need to be bought.

Children of school age are capable of making their own decisions about many things. Parents may need to put some work into motivating their children to want to go to school in their free time. However much fun you try to make it, reading and writing are very like what the children do all week at school. If they are not motivated, they will not enjoy their Saturday school, and are unlikely to learn very much.

Good luck in anything you organise for your children!

Keeping track

Documenting a child’s linguistic development

The sheets provided here are intended for you to use to keep track of your child’s acquisition of languages. They are in Word format so you can easily edit them, or use them for inspiration for making your own sheets on a computer using a word processor or a spreadsheet. Have a file or notebook especially for your notes about your child’s languages. You can record anything else you notice about your child’s linguistic progress. You can use these sheets to see if one language is maybe racing ahead of the other. This may be known and expected, but the sheets give a measure of what is going on and a chance to see if anything the family changes has an effect on the development of the child's languages.

Vocabulary

There are several ways you could keep track of your child’s acquisition of languages. One way is to measure vocabulary size at different stages. The Vocabulary sheet can be used to document and compare the child’s vocabulary in both languages. You can start by writing the child’s first 50 words in each language, and letting the next snapshot be six months later. For children up to three or four you can use a picture book of the kind that has pictures of maybe 100 everyday objects without any text. The idea is that each parent (or other person the child uses each of the two languages with) sits in turn with the child and goes through the book, talking about the pictures, seeing which objects the child can name.

For older children you can find a picture book of the kind that has very detailed pictures with lots going on, ideally so that there is no text visible on the page, or cards that show pictures of familiar objects. The level of difficulty can be increased as the child’s language develops. Have a range of material each time, so there are always some words the child knows in both languages. Make the documentation into a game, and give children only positive feedback, concentrating on what they know rather than what they do not know. Use the documentation as a chance to teach new vocabulary and talk about new words. If you repeat the activity in each language after six months you will see that the child’s vocabulary has increased.

Download Fifty first wordsLength of utterance

You may also want some way of documenting and comparing the child’s progress in learning to put words together in each language. The child’s mean length of utterance (MLU) is a measure often used in child language research, where concepts such as ‘the two-word stage of language development’ (when a child typically uses two-word sentences such as “Mummy come”) have been found useful. The MLU sheet is intended to be used in conjunction with recordings of the child's speech in each language, about 15 chatty minutes in each language. On the MLU sheet you can write out 100 consecutive sentences from the child’s speech in each language, such as “mine!”, “more milk” or “I don’t want to go to school”. If you have difficulty deciding where a particular utterance ends, leave that one out. You can count the total number of words in the 100 sentences then divide by 100 which gives the mean length of utterance. The above utterances have one, two and seven words, respectively. Up to a certain age you can follow your child’s mean length of utterance as it increases in each language. The assumption is that longer utterances are a sign of more complex sentence structures, but after a certain level is reached the measure does not reflect language development, since sentences can become more complex without getting longer and vice versa.

Download MLU sheetPronunciation

All children have difficulties with the pronunciation of some of the sounds of a language. Some sounds are simply harder to make than others, such as words where two or more consonants come together at the beginning and/or end of the word, for example, blanket, stop, crunched. Other sounds are difficult in themselves, such as the <th> sounds in think or the.

The Pronunciation sheet is meant for you to document your child’s pronunciation. The idea is that you listen out for problems in your child’s speech. Some of the problems will be of the kind that a monolingual child might have, while others will clearly be a kind of foreign accent. You can use any of the material you have recorded, but if you want to get children to try to say a certain sound you can ask them to read a simple sentence with the sound in or show them a picture of an object whose name contains the sound, or you can say sentences to them and have them repeat after you. It can be very difficult to spot children’s pronunciation difficulties when you are speaking to them, but if you record their speech and listen afterwards, you might notice all kinds of things. You may wish to help your children practise special sounds if they have difficulty with them.

Children with two languages may sometimes speak their minority language with an accent like speakers of the majority language have when they speak the minority language. This probably means that the child is using some of the nearest sounds of the majority language instead of minority language sounds and may be following the phonological rules of the majority language in other ways too, so that a Spanish and French-speaking child in Spain may have difficulty pronouncing a French word which begins with <sp>, so that, for example, sport is pronounced esport. A Swedish and English-speaking child in Sweden may be reluctant to pronounce the final sound in words like was as /z/ rather than as /s/.

The point of keeping track is to spot any problems and to see how children progress through the sounds and sound combinations of their languages. In the Pronunciation sheet you can write the word the child is aiming at and describe what the child is doing wrong. Next time round, say after six months, you can try the problem words again. If the child’s pronunciation has improved you may discover new challenges which were not noticeable before.

Download Pronunciation sheet I want to use the toilet

I want to use the toilet I’m thirsty

I’m thirsty