Chapter 4: Core Concepts for Teaching Social Justice Education

Maurianne Adams, Rani Varghese, Ximena Zúñiga

Using Resources

These resources are more effective when used in conjunction with the book.

Buy NowA. Quadrant Grid

B. Text embedded below quadrant grid:

Quadrant 1

Welcome

Name of Activity: Core Concepts: Welcome, Meet and Greet – Option A for Quadrant 1, Chapter 4:

Instructional Purpose Category:

- Icebreakers

- Tone Setting/ developing group guidelines

Instructional Purpose: The purpose of this activity is to ease the way for participants to meet each other.

Learning Outcomes: After this activity participants will have had a chance to meet and connect with several members of the class or workshop.

Time Needed: 20-25 minutes

Materials Needed: Provide“Meet & Greet” handout (update as needed) as a digital link for the document or printed as needed

Degree of Risk: Low-risk

Procedure: 1Explain to participants that this activity is meant to help them begin to get to know each other by having one-minute conversations on specific topics. Participants introduce themselves to someone, have a discussion about an item on the sheet, and then they have their speaking partner pencil their initials on the sheet. The activity is meant to encourage participants to introduce themselves and chat with as many people as possible. Note that some items require talking to people who have had specific experiences, while others can be explored with anyone. The items do not have to be discussed in order. Tell participants that they have about 20 minutes (adjust accordingly). Ask if anyone has questions. Pass out the handouts and instruct participants to begin by finding someone they do not know well.

Facilitation Notes & Considerations: It is important to highlight that the activity is not a contest; there is no prize for collecting all of the signatures as quickly as possible. Facilitators are welcome to adapt the “Meet & Greet” handout depending on the participants and context, keeping in mind that this is meant to be a low-risk introductory activity with participants who are unfamiliar with each other. Also note that twenty minutes may be a long time for some participants to stand; invite them to sit as necessary. Ensure that there is an open space for people with mobility impairments to move around the room.

Recommended Materials/Readings for Students: None

Recommended Supplementary Materials/Readings for the Facilitator: None

Name(s) to credit for this activity:

- Updated by Ximena Zúñiga & Itza Martínez (2021) from

- Adaptation by McDonald, J., and Zúñiga, X., (2015). Meet and Greet. Teaching for diversity and social justice. (2nd ed.). Routledge.

- Molly Keehn, Social Justice Education, University of Massachusetts Amherst (2010) and

- Kathy Obear, The Human Advantage (1991)

1If conducting this activity on a digital platform such as Google Meet, Zoom, or other, be mindful of how the facilitator will create small breakout groups and support them (via chat or through digital access to materials).

Name of Handout: Core Concepts: Ice Breaker: Meet and Greet Handout – Option A for Quadrant 1, Chapter 4

Meet and Greet

Introduce yourself: Name, gender pronouns (if you choose), and where you grew up.

Get 1 signature from each person you meet for 1 of the following items and have a conversation with each person for about one minute.

- Chat about two exciting activities you have done recently ____________

- Find someone who prefers cold weather to warm weather

- Find someone who is fluent in a language other than English ____________

- Talk to someone who is a vegetarian ____________

- Talk about where you see yourself in five years ____________

- Chat with someone who can raise one eyebrow ____________

- Talk to someone who is a first-generation student ____________

- Find someone who is a parent ____________

- Chat with to someone about what brings you both joy

- Chat with someone who sings in the shower ____________

- Talk about a favorite book related to your studies or interests ____________

- Find someone who has more than three siblings ____________

- Talk to someone who loves working in small groups ____________

- Find someone who plays a musical instrument ____________

- Talk about how you feel about being here today ____________

Credits:

- Adapted by Itza Martinez and Ximena Zúñiga (2021) from:

- Ximena Zúñiga and Jess McDonald (2015),Teaching for diversity and social justice companion website. (3rd., ed.). Routledge.

- Molly Keehn, Social Justice Education, University of Massachusetts Amherst (2010) and Kathy Obear, The Human Advantage (1991).

Instructional Purpose Category:

- Icebreakers

- Tone setting / developing group guidelines

Instructional Purpose: The purpose of this activity is to provide participants with a speak and listen structure in the large group to share perspectives, feelings and experiences on issues that are relevant for building a learning community using a speak-and-listen structure.

Learning Outcomes: After this activity participants will practice speaking and listening and get to know members of the class or workshop

Time Needed: 30 minutes

Materials Needed: Determine questions and sequencing

Degree of Risk: Depends on questions posed; best to use low-risk questions if used early in a course or workshop; if used midway, increase risk level as appropriate or desired.

Procedure1: Situate the participants into two concentric circles facing one another—one inner circle facing outward and another circle around the inner circle facing toward the inner circle. The participants can be sitting or standing. Explain that you will be asking questions to the group using a speak-and-listen structure where one person gets three minutes to answer the question while the other person practices silent active listening, and then the roles switch. Pose a question or topic to the group.

- For example: Share your name and what brings you here today. Instruct the people in the inner circle to answer the question for three minutes; once three minutes pass, tell the participants to switch roles. After both partners have shared, instruct the people in the inner circle to move one or two people (or seats) to the right.

After moving, everyone should be facing a new partner. Ask a second question.

- For example: What is one hope you have about this course or workshop? Give each person three minutes to answer, and then have the inner (or outer) circle move one or two space(s) again so that the participants face a new partner for the next question. Other possible questions or topics to discuss include: “For me, I learn best when . . .”; “For me, I do not learn well when . . .”; “My major challenges this month are . . .”; “My support systems right now include . . .”; etc.

Repeat this process until all questions are answered.

Debrief the activity in small groups or as a large group. This can be a general discussion on thoughts, observations, and feelings that came up during the exercise. Possible questions to ask include which questions were particularly easy or difficult to answer, which questions were most interesting, what the participants learned about themselves and others, and how these conversations connect to the larger topic being examined.

Facilitation Notes & Considerations: Ideally this activity works well with 14 – 16 participants, although it can be done with larger and smaller numbers. The questions used in the exercise depend largely on the focus or goals of the session and can be modified accordingly. You may want to process the activity, by asking participants which questions were particularly easy or difficult to answer, which questions were more engaging and why, and what things they learned about themselves from conversations with other participants. The facilitator can choose whether or not to participate depending on whether there is an odd or even number of participants. Ensure that there is enough space for people with mobility needs to move as necessary or consider making one of the concentric circles stationary if this is not possible.

Recommended Materials/Readings for Students: None

Recommended Supplementary Materials/Readings for the Facilitator: None

Name(s) to credit for this activity:

- Adapted by Maurianne Adams and Ximena Zúñiga (2021) from

- Myers, P. & Zúñiga, X. (1993). Classroom and workshop exercises: Concentric circles exercise. In D. Schoem, L. Frankel, X. Zúñiga, & E. Lewis (Eds.), Multicultural teaching in the university (pp. 318–319). Praeger.

1If conducting this activity on a digital platform such as Google Meet, Zoom, or other, be mindful of how the facilitator will create small breakout groups and support them (via chat or through digital access to materials)

Introductions

Name of Activity: Core Concepts Introductions in Dyads – Option A for Quadrant 1, Chapter 4

Instructional Purpose Category:

- Icebreakers

- Tone setting / developing group guidelines

Instructional Purpose: The purpose of this activity is to introduce participants to each other.

Learning Outcomes: After this activity participants will be more acquainted with each other.

Time Needed: 30 minutes

Materials Needed: None

Degree of Risk: Low-Risk

Procedure1: Explain to participants that this activity involves two steps, pairing and sharing. Use this opportunity to also introduce yourself and any other facilitators. You might also consider sharing a story about your first experience taking a social justice workshop or course. This helps ease the participants’ anxieties and models personal disclosure and authenticity which is valuable in helping set the tone in a workshop or course.

First, they will get in pairs and each take turns answering prompts and then folks will switch partners and repeat the process of answering the prompts. Second, instruct the participants to find a partner and introduce themselves by responding to the following prompts (written on newsprint or slide) in three minutes:

- Name,

- Pronouns2

- Their area of study or work,

- What led them to join workshop or course,

- One hope they have about the workshop or course

A speak-and-listen activity asks partners to take turns speaking and listening without interruption. The facilitators will keep the timing and inform participants.

Facilitation Notes & Considerations: It is important to give participants the opportunity to share one-on-one. In order to build interpersonal connections, support different personality types, and serve diverse learning styles. If conducting this in person, consider mobility adaptations. If conducting this activity via a digital meeting platform such as Google Meet or Zoom, consider creating breakout rooms beforehand.

Recommended Materials/Readings for Participants: None

Recommended Supplementary Materials/Readings for the Facilitator: None

Name(s) to credit for this activity:

- Adapted by Ximena Zúñiga & Itza D. Martínez (2021) from:

- McDonald, J & Zúñiga, X., Teaching for diversity and social justice companion website. (3rd., ed.). Routledge, and

- Hardiman, R., Jackson, B., & Griffin, P. (2007). Conceptual foundations for social justice education. In M. Adams, L. A. Bell, & P. Griffin (Eds.), Teaching for diversity and social justice (2nd ed., pp. 35–66). Routledge.

- Zúñiga, X. (2021; 2015), EDUC 202: Exploring social/cultural difference and commonalities intergroup dialogue curriculum. Social Justice Education, University of Massachusetts-Amherst.

1If conducting this activity on a digital platform such as Google Meet, Zoom, or other, be mindful of how the facilitator will create small breakout groups and support them (via chat or through digital access to materials)

2For more information about pronouns, see Shlasko, D., (2017), Trans Allyship Workbook: Building Skills to Support Trans People In Our Lives. Think Again Training, Revised edition

Name of Activity: Introductions, Sharing Our Names (Core Concepts), Option B for Quadrant 1, Chapter 4

Instructional Purpose Category:

- Icebreakers

- Tone setting / developing group guidelines

Instructional Purpose: The purpose of this activity is for participants to introduce themselves to each other in ways that are memorable in connection to the social justice issue that is the focus of the course or workshop.

Learning Outcomes: After this activity participants will have had a chance to share a personal story related to their name and listen to their peers’ stories.

Time Needed: Varies depending on the size of the group and length of the session. Plan for approximately 1-3 minutes per participant.

Materials Needed: None

Degree of Risk: Varies depending on the facilitator’s modeling and disclosure level

Procedure1: This activity is meant to happen early in a session when the participants are first getting to know one another. Situate the participants in a circle facing inward; they may be standing or sitting. Explain that this activity is meant to help them get to know each other better as well as start thinking critically about the topic at hand. Explain why familiarity with each other’s names is important in the workshop or course and acknowledge the social significance of names and naming. For instance, our first, middle, and last names—and the processes by which we attain them—can tell us much about our background and life experiences, but we often do not think critically about them. Our names may be deeply connected to religious traditions, gender identity, ethnicity, nationality, family history, or have other cultural significance.

The facilitator role models the activity by introducing their name(s) and their significance. Here are several examples of what one of the co-editors of this book, Maurianne Adams, might share to model this activity:

- My first name, Maurianne, is a Christian name (Mary and Anna), although my family is Jewish. For me, it illustrates the ways in which my maternal German ancestors were assimilated Germans, since I am named after my mother’s grandmother, Marianna. It is also interesting that the Jewish version of my name, Miriam, is my father’s mother’s name.

- If I was facilitating a class in Sexism, I might say something like this: My last name, Adams, is interesting because it is such a common, Anglo name. I took it from my first marriage. I find it curious now, looking back, that I gave up my own family name for his. At the time I married, in 1971, it never occurred to me to keep my family name.

- If I was facilitating a class in Religious Oppression, I might say something like this: It is entirely possible that I took my husband’s name because of my own internalized antisemitism, in that I was willing to give up an unusual name such as Schifreen, since so many people asked me “What kind of name is that?” or “How do you pronounce it?” Adams was much easier to manage.

- In a Religious Oppression class, I might tell this somewhat more “high risk” story about my name: I was 7 years old in 1945 when World War II was over; the allied soldiers had opened and liberated the concentration and death camps, and my family had learned of the deaths of our family members in Germany. One of them, a girl slightly older than I, was named Marianne and I knew that in German it was pronounced the way my name is spelled, Maurianne. Even at age 7, I felt a special connection with her, between my life and her death. It gave me a special sense of purpose, even as a young child, to make sure my life was worthwhile. There is a clear through-line from this commitment as a child and the work I do as a social justice educator today.

After sharing, the facilitator or facilitators then ask for a volunteer to share next and continue with group introductions from there. If there is time, the facilitator(s) may debrief the activity by asking participants to name themes they heard across the group and how these themes relate to the workshop or course topic(s).

Facilitation Notes & Considerations: The way the facilitator or facilitators model this activity will influence what and how much participants are moved to say. These are important decisions of relevance: the connection of what we say about our names and the course topics—and disclosure—how personal or deep it seems appropriate to go, so early in the class. How one models this activity also involves tone (balance between seriousness and humor), comfort level with the material, and the size of the group. If the group has more than 25 participants, including the facilitator(s), it will be necessary to keep each introduction brief. For this, the co-author mentioned above might merely say that she was named after maternal and paternal grandparents and that her name has Christian (Mary Anna) as well as Jewish (Miriam) family associations, or that she took the surname of her husband and now realizes that it never occurred to her to keep her family name.

The participants are sometimes embarrassed to acknowledge that it never occurred to them to think about their names—or that they were named after a popular film star or athlete. The facilitator can comment that this will be an interesting topic the next time the participants talk with their family members—or that being named after a famous person is an interesting historical or cultural fact to be aware of. Why one film star or athlete and not another?

Recommended Materials/Readings for Participants: None

Recommended Supplementary Materials/Readings for the Facilitator: None

Name(s) to credit for this activity:

- Adams, M., & Hahn d’Errico, K. (2007). Antisemitism and anti-Jewish oppression curriculum design (Chapter 12, Handout 12H). In M. Adams, L. A. Bell, & P. Griffin (Eds.), Teaching for diversity and social justice (2nd ed., pp. 285–308). Routledge.

1If conducting this activity on a digital platform such as Google Meet, Zoom, or other, be mindful of how the facilitator will create small breakout groups and support them (via chat or through digital access to materials).

Name of Activity: Introductions, Common Ground (Core Concepts), Option C for Quadrant 1, Chapter 4

Instructional Purpose Category:

- Icebreakers

- Tone setting / developing group guidelines

Instructional Purpose: The purpose of this activity is to provide participants with the opportunity to explore commonalities and differences around a particular topic and to begin to establish a more personal framework for participants to understand the topic being discussed.

Learning Outcomes:After this activity participants will have gotten to know their group mates.

Time Needed: 30 minutes

Materials Needed: List of statements, copies for participants (optional) either printed or digital link for the document

Degree of Risk: Low-risk; varies depending on statements

Procedure1: In advance, prepare statements to emphasize various social identities and their related experiences held by participants in the class. Also provide statements that identify experiences that you believe are not represented in the group.

Ask the participants to form a circle. Explain that as statements are called out, the participants for whom the statement is true will enter the circle, and then stand there for a moment. In that moment, the participants will look at who has joined the inner circle and who remains in the outer circle. The participants who joined the inner circle will return to the full group for the next statement. Begin the activity. Depending on the topic, risk level, and group, the facilitator may invite the participants to make up other categories as you go or invite the participants to call other categories that apply to them. For example, in a new group you could ask the participants to move to the center and do common ground with everyone who . . .

- Eats breakfast every morning

- Got five or less hours of sleep last night

- Grew up in the US (or is a citizen of another country.)

- Is the youngest child in your family (or oldest, middle, only, twin)

- Grew up in a city (rural, small town, suburbs)

- Speaks more than one language

- Works full-time (or part-time, when available)

- Is raising children

- Likes small-group discussions (or large groups, pair share)

- Identifies as an introvert (or extrovert)

- Is a first-generation student

- Enjoys online learning (or in person or hybrid learning)

Thank the participants for participating and ask them to return to their seats (if conducting the activity this way). Depending on the size of the group, utilize a pair-share or large-group discussion to debrief the activity. Prompts for discussion might include: How did this activity feel? What stood out for you? Did you notice any patterns personally or in the group? What did you learn about yourself or about the group from this activity?

Facilitation Notes & Considerations: This activity can be used as a low-risk icebreaker, a medium-risk bonding activity, or a high-risk conversation starter. Gauge your use of this activity depending on how well the group knows each other and the goals of the session. Depending on the issues addressed in the activity, the participants may be asked if they have a statement to add. In some cases, the facilitator may direct the participants to offer only statements that apply to themselves (i.e., ones that they will “step in” for). With high-risk topics of discussion such as gender-based violence, it is not recommended to ask the participants for additional statements.

For medium- or high-risk activities, more debriefing will be necessary. The facilitator may instruct the participants to do a pair-share or small-group debrief following the activity. Additional questions might include: What did you notice as you and others were going in and out of the circle? What surprised you? What was uncomfortable for you? What was comfortable? If the activity is used as a discussion starter, it may be helpful to provide copies of the statements after the activity is completed in order for participants to reference back to them.

Recommended Materials/Readings for Participants: None

Recommended Supplementary Materials/Readings for the Facilitator: None

Name(s) to credit for this activity:

- Adapted by Ximena Zúñiga and Jess McDonald (2015). Teaching for diversity and social justice companion website (3rd., ed.). Routledge from:

- Yeskel, F., & Leondar-Wright, B. (1997). Classism curriculum design. In M. Adams, L. A. Bell, & P. Griffin (Eds.), Teaching for diversity and social justice (2nd ed., pp. 232–251). Routledge.

1If conducting this activity via a digital platform such as Google Meet or Zoom, instead of forming a circle and having participants step in/out, have participants turn on/off their cameras or have all cameras on and use a reaction to “step in” to the circle. If facilitating in person, an adaptation may be to allow participants to be seated in a circle and raise their hand if the statement applies to them.

Learning Community

Name of Activity: Learning Community – Option A: Group Guidelines (Core Concepts) (Abbreviated Version) in Quadrant 1, Chapter 4

Instructional Purpose Category:

- Icebreakers

- Tone setting /developing group guidelines

Instructional Purpose: The purpose of this activity is to begin to explore participants’ hopes and concerns about participating in the group and identify guidelines that can help build trust and a sense of safety as part of the group process before diving into potentially challenging content.

Learning Outcomes: Students will have experienced the opportunity to generate hopes and concerns as well as guidelines in order to begin to clarify what is needed to build trust and a sense of safety in the group.

Time Needed: 20-30 minutes

Materials Needed: Newsprint and markers; or use digital interactive platforms such as a digital whiteboard, accessible slide deck, Padlet, Jamboard, or Miro board

Degree of Risk: Low to medium risk

Procedure1: Because students find themselves challenged by the course content and the class process is experiential and interactive, it is helpful to generate some baseline guidelines to facilitate the group process and develop trust. Ask the participants to identify guidelines that would help them participate fully in class activities. This can be accomplished in groups of three to five and then shared with the whole group or brainstormed as a whole-group activity. Some of the baseline guidelines we find helpful include the following:

- Set own boundaries for sharing

- Speak from your own experience and avoid generalizations

- Respect confidentiality (do not share personal information shared in class outside the class)

- Share airtime

- Listen respectfully to different perspectives

- No blaming

- Focus on own learning

- Explore your emotional reactions, perceptions, & assumptions

- Ask clarifying questions as needed

- Participate honestly/openly pass

As each guideline is proposed, ask the participants to identify benchmarks or indicators of each guideline so that the meaning of the guideline becomes understood and shared. For example, how will they “know” if respect or listening is happening, or what safety means? Allow discussion about each item before proceeding to the next one, and make sure that each participant understands the meaning and allow for different indicators or forms of expression.

Facilitation Notes & Considerations: Note that a longer version of this activity is available in Quadrant 1, Learning Community, and Option B: Hopes/Concerns & Group Guidelines (Longer Version). Should you decide to address comfort zones, learning edges, and activations or emotional reactions refer to the Activity titled “Comfort Zones, Learning Edges, and ‘Activations’, Chapter 4, Quadrant 1”. As various guidelines are offered, the facilitators may identify cultural, linguistic, generational, or gendered differences that are embedded in the conversation about guidelines. The indicators of listening, for example, may vary within and between cultures. It is important to begin to note how our various “identity lenses” impact what we see and how we make sense of what we see. The facilitator may also need to pose questions in relation to some guidelines to clarify meaning. For example, if safety is mentioned, note that there is a difference between being safe and being comfortable so that the group does easily equate experiencing tension or confusion with not being safe. Depending on the length of the course, use these guidelines as a reference point for processing group interaction. Periodically through the course, ask how successful the group has been in adhering to the guidelines; ask if there are other guidelines to add, delete, modify, or clarify. Additionally, be careful not to have too many guidelines that limit or restrict communication, honesty, and difference of experience (based on culture, language, age, gender, etc.).

Recommended Materials/Readings for Students:

Adams, M., Zúñiga, X., (2018). Core Concepts for Social Justice Education. Readings for Diversity in Social Justice. In Adams, M., Blumenfeld, W.J., Catalano, D. C. J., DeJong, K., Hackman, H.W., Hopkins, L.e., Love, B.J., Peters, M. L., Shlasko, D., Zúñiga, X., (4th ed., pp. 41 – 49). Routledge.

brown, a.m. (2021). Holding Change The way of emergent strategy facilitation and mediation. A.K. Press.

Lakey, G. (2020). Facilitating Group Learning: Strategies for success with adult learners. (2nd edition). PM Press.

Recommended Supplementary Materials/Readings for the Facilitator:

Adams, M., Zúñiga, X., (2018). Core Concepts for Social Justice Education. Readings for Diversity in Social Justice. In Adams, M., Blumenfeld, W.J., Catalano, D. C. J., DeJong, K., Hackman, H.W., Hopkins, L.e., Love, B.J., Peters, M. L., Shlasko, D., Zúñiga, X., (4th ed., pp. 41 – 49). Routledge.

brown, a.m. (2021). Holding Change The way of emergent strategy facilitation and mediation. A.K. Press.

Lakey, G. (2020). Facilitating Group Learning: Strategies for success with adult learners. (2nd edition). PM Press.

Name(s) to credit for this activity:

- Adapted by Ximena Zúñiga & Itza D. Martínez (2021) from:

- Hardiman, R., Jackson, B., & Griffin, P. (2007). Conceptual foundations for social justice education. In M. Adams, L. A. Bell, & P. Griffin (Eds.), Teaching for diversity and social justice (2nd ed., pp. 35–66). Routledge.

- Zúñiga, X. (2021; 2015). EDUC 202: Exploring social/cultural difference and commonalities intergroup dialogue curriculum. Social Justice Education, University of Massachusetts-Amherst.

1If conducting this activity on a digital platform such as Google Meet, Zoom, or other, be mindful of how the facilitator will create small breakout groups and support them (via chat or through digital access to materials).

Name of Activity: Learning Community – Option A: Group Guidelines (Core Concepts) (Abbreviated Version) in Quadrant 1, Chapter 4

Instructional Purpose Category:

- Icebreakers

- Tone setting /developing group guidelines

Instructional Purpose: The purpose of this activity is to begin to explore participants’ hopes and concerns about participating in the group and identify guidelines that can help build trust and a sense of safety as part of the group process before diving into potentially challenging content.

Learning Outcomes: Students will have experienced the opportunity to generate hopes and concerns as well as guidelines in order to begin to clarify what is needed to build trust and a sense of safety in the group.

Time Needed: 20-30 minutes

Materials Needed: Newsprint and markers; or use digital interactive platforms such as a digital whiteboard, accessible slide deck, Padlet, Jamboard, or Miro board

Degree of Risk: Low to medium risk

Procedure1: Because students find themselves challenged by the course content and the class process is experiential and interactive, it is helpful to generate some baseline guidelines to facilitate the group process and develop trust. Ask the participants to identify guidelines that would help them participate fully in class activities. This can be accomplished in groups of three to five and then shared with the whole group or brainstormed as a whole-group activity. Some of the baseline guidelines we find helpful include the following:

- Set own boundaries for sharing

- Speak from your own experience and avoid generalizations

- Respect confidentiality (do not share personal information shared in class outside the class)

- Share airtime

- Listen respectfully to different perspectives

- No blaming

- Focus on own learning

- Explore your emotional reactions, perceptions, & assumptions

- Ask clarifying questions as needed

- Participate honestly/openly pass

As each guideline is proposed, ask the participants to identify benchmarks or indicators of each guideline so that the meaning of the guideline becomes understood and shared. For example, how will they “know” if respect or listening is happening, or what safety means? Allow discussion about each item before proceeding to the next one, and make sure that each participant understands the meaning and allow for different indicators or forms of expression.

Facilitation Notes & Considerations: Note that a longer version of this activity is available in Quadrant 1, Learning Community, and Option B: Hopes/Concerns & Group Guidelines (Longer Version). Should you decide to address comfort zones, learning edges, and activations or emotional reactions refer to the Activity titled “Comfort Zones, Learning Edges, and ‘Activations’, Chapter 4, Quadrant 1”. As various guidelines are offered, the facilitators may identify cultural, linguistic, generational, or gendered differences that are embedded in the conversation about guidelines. The indicators of listening, for example, may vary within and between cultures. It is important to begin to note how our various “identity lenses” impact what we see and how we make sense of what we see. The facilitator may also need to pose questions in relation to some guidelines to clarify meaning. For example, if safety is mentioned, note that there is a difference between being safe and being comfortable so that the group does easily equate experiencing tension or confusion with not being safe. Depending on the length of the course, use these guidelines as a reference point for processing group interaction. Periodically through the course, ask how successful the group has been in adhering to the guidelines; ask if there are other guidelines to add, delete, modify, or clarify. Additionally, be careful not to have too many guidelines that limit or restrict communication, honesty, and difference of experience (based on culture, language, age, gender, etc.).

Recommended Materials/Readings for Students:

Adams, M., Zúñiga, X., (2018). Core Concepts for Social Justice Education. Readings for Diversity in Social Justice. In Adams, M., Blumenfeld, W.J., Catalano, D. C. J., DeJong, K., Hackman, H.W., Hopkins, L.e., Love, B.J., Peters, M. L., Shlasko, D., Zúñiga, X., (4th ed., pp. 41 – 49). Routledge.

brown, a.m. (2021). Holding Change The way of emergent strategy facilitation and mediation. A.K. Press.

Lakey, G. (2020). Facilitating Group Learning: Strategies for success with adult learners. (2nd edition). PM Press.

Recommended Supplementary Materials/Readings for the Facilitator:

Adams, M., Zúñiga, X., (2018). Core Concepts for Social Justice Education. Readings for Diversity in Social Justice. In Adams, M., Blumenfeld, W.J., Catalano, D. C. J., DeJong, K., Hackman, H.W., Hopkins, L.e., Love, B.J., Peters, M. L., Shlasko, D., Zúñiga, X., (4th ed., pp. 41 – 49). Routledge.

brown, a.m. (2021). Holding Change The way of emergent strategy facilitation and mediation. A.K. Press.

Lakey, G. (2020). Facilitating Group Learning: Strategies for success with adult learners. (2nd edition). PM Press.

Name(s) to credit for this activity:

- Adapted by Ximena Zúñiga & Itza D. Martínez (2021) from:

- Hardiman, R., Jackson, B., & Griffin, P. (2007). Conceptual foundations for social justice education. In M. Adams, L. A. Bell, & P. Griffin (Eds.), Teaching for diversity and social justice (2nd ed., pp. 35–66). Routledge.

- Zúñiga, X. (2021; 2015). EDUC 202: Exploring social/cultural difference and commonalities intergroup dialogue curriculum. Social Justice Education, University of Massachusetts-Amherst.

1If conducting this activity on a digital platform such as Google Meet, Zoom, or other, be mindful of how the facilitator will create small breakout groups and support them (via chat or through digital access to materials).

Comfort Zones

Name of Activity: Comfort Zones, Learning Edges, and “Activations” Interactive Lecture (Core Concepts) , Chapter 4, Quadrant 1

Instructional Purpose Category:

- Processing / debriefing the process

- Terminology /exploring language

Instructional Purpose:The concepts of comfort zones, learning edges, and activations can serve as guides to help participants understand and explore their emotional reactions to activities and other participants’ perspectives. Typically, this information is presented prior to creating group norms and participation guidelines.

Learning Outcomes:After this activity participants will understand their own and others’ sense of comfort zones, learning edges, and activations.

Time Needed:15-30 minutes

Materials Needed: Post definitions on the board or flip chart paper or digital interactive platforms such as a digital whiteboard, accessible slide deck, Padlet, Jamboard, or Miro board; print handout or provide digital link to “Responding to Hot Buttons or Emotional Intensity” Handout (optional).

Degree of Risk: Mostly low-risk, some medium-risk

Procedure1: Explain to the participants that social justice education courses are different from other courses in several ways. These conversations, often seen as taboo and in diverse groups, can bring up emotions and reactions that are not typically a part of standard classroom experiences or workshops, but they are an important part of the learning process in social justice education. Encourage the participants to embrace this process and explain that the following concepts will assist them in thinking about how to do this. Introduce the following concepts so the participants are cognizant of the following personal spaces/edges:

Comfort Zone: We all have zones of comfort about different topics or activities. Topics or activities we are familiar with or have lots of information about are solidly inside our comfort zone. When we are inside our comfort zone, we are not challenged, and we are not learning anything new. When we are participating in a discussion or activity focused on new information or awareness, or the information and awareness we have or are familiar with is being challenged, we are often out of our comfort zone or on its edge. If we are too far outside our comfort zone, we tend to withdraw or resist new information. The goal in this course is to learn to recognize when we are on the edge of our comfort zone.

Learning Edge: When we are on the edge of our comfort zone, we are in the best place to expand our understanding, take in a new perspective, and stretch our awareness. We can learn to recognize when we are on a learning edge in this course by paying attention to our internal reactions to class activities and other people in the class. Being on a learning edge can be signaled by feelings of annoyance, anger, anxiety, surprise, confusion, or defensiveness. These reactions are signs that our way of seeing things is being challenged. If we retreat to our comfort zone by dismissing whatever we encounter that does not agree with our way of seeing the world, we lose an opportunity to expand our understanding. The challenge is to recognize when we are on a learning edge and then to stay there with the discomfort we are experiencing to see what we can learn (Griffin, Hardiman, & Jackson, 2007).

Explain that the group is now going to take some time to think about their own experiences with comfort zones and learning edges. The facilitator or facilitators should share some examples from their own lives to model self-disclosure and to help participants to understand what you are asking them to identify. For example, talk about learning a new sport, skill, or dance; taking a difficult academic course; or being in another country where you were not familiar with the culture or language. Ask the participants to take two minutes each to share with a partner a time they can remember being on a learning edge with new information or a new skill. Ask the participants to respond to this question: What internal cues will alert you that you are on a learning edge in this course? Encourage the participants to recognize that pounding hearts, sweaty palms, butterflies in the stomach, excited focused attention, confusion, fear, and anger are all cues to recognize personal learning edges. Bring the group together again and explain that it is important for the participants (and the facilitators) to recognize when and how their emotional reactions might be impacting their participation in the course or workshop. When aware of these reactions, we can name them and work through them in order to keep learning rather than shut down. Introduce the concept as presented by Griffin, Hardiman, & Jackson (2007):

Activations: These are words or phrases that stimulate a strong emotional response because they tap into anger or pain about oppression issues.. Activations do not necessarily threaten one’s physical safety but rather make us feel psychologically threatened. We can also be activated based on our own social identity group or on behalf of another social identity group. Though we may not feel personally threatened, our sense of social justice is challenged or even violated.

Examples of activations include:

- “I don’t see differences; people are people to me.”

- “What do you people really want anyway?”

- “I think men are just biologically more adapted to leadership roles than women.”

- “I feel so sorry for people with disabilities. It’s such a tragedy.”

- “If everyone just worked hard, they could achieve.”

- “Homeless people prefer their life.”

- “I think people of color are blowing things way out of proportion.”

- “If women wear tight clothes, they are asking for it.”

Ask the participants how they might respond to feeling activated. Acknowledge that there are a variety of responses, from leaving the space to sitting in silence to attacking the person who activated us. We might also name our emotional reactions, invite discussion about it, and strategize about how to move forward. Obviously, some of these responses are more helpful than others, and one of the group’s goals is to be able to name activations and work through them. Invite the group to identify a process for naming activations and learning edges in ways that encourage open and respectful dialogue. This could be as simple as inviting participants who feel activated or on a learning edge to say so. Explain that this can be a significant learning opportunity for everyone in the course and often is a “breakthrough” experience because the learning is in “real time,” as the moment is unfolding. Encourage the person who activated someone else to listen and try to understand what was upsetting about their comment. Ask them to listen rather than defend their comment.

Encourage the participants to view these discussions as “food for thought” rather than attempts to change an individual participant’s views on the spot. Remind them that no one can focus effective attention on personal learning when they feel defensive or chastised. If time allows or if the facilitator(s) feel(s) it is necessary, they can also pass out the “Responding to Hot Buttons or Emotional Intensity” handout. It is recommended that the facilitator then transitions to the “Hopes/Concerns and Group Guidelines (longer or abbreviated versions” activity.

Facilitation Notes & Considerations: Many participants come into social justice education courses with some fear that they will “make a mistake” by activating someone else. Encourage the participants to look at activations as learning opportunities for everyone. It is important to note that anyone can say something that can activate anyone else, regardless of social group membership. Sometimes members of privileged groups may activate members of targeted groups and vice versa and members of privileged groups are activated by what other members of their group say and targeted group members can be activated by someone from their own group as well.

Recommended Materials/Readings for Participants: None

Recommended Supplementary Materials/Readings for the Facilitator:

Hardiman, R., Jackson, B., & Griffin, P. (2007). Conceptual foundations for social justice education. In M. Adams, L. A. Bell, & P. Griffin (Eds.), Teaching for diversity and social justice (2nd ed., pp. 35–66). Routledge.

Name(s) to credit for this activity:

- Adapted by Ximena Zúñiga & Itza D. Martínez (2021) from:

- Hardiman, R., Jackson, B., & Griffin, P. (2007). Conceptual foundations for social justice education. In M. Adams, L. A. Bell, & P. Griffin (Eds.), Teaching for diversity and social justice (2nd ed., pp. 35–66). Routledge.

1If conducting this activity on a digital platform such as Google Meet, Zoom, or other, be mindful of how the facilitator will create small breakout groups and support them (via chat or through digital access to materials).

Name of Handout: Responding to “Hot Buttons” or Emotional Intensity (Core Concepts), Chapter 4, Quadrant 1

What an individual says or does, or an organizational policy or practice may generate a strong emotional response in a way that “hooks” us. It may make us feel diminished, offended, threatened, stereotyped, discounted, or attacked. These emotional responses are what we are naming as activations (Obear, 2013). Activations do not necessarily threaten our physical safety but instead may make us feel psychologically threatened. We can also be activated based on our own social identity group or on behalf of another social identity group. Though we may not feel personally threatened, our sense of social justice is challenged or even violated.

Certain content, behaviors or words can cause an emotional response. These emotions range from hurt, confusion, anger, and fear to surprise or embarrassment. We may respond to these activations in a variety of ways, some helpful and others not. What responses we choose depends on our own inner resources and the dynamics of the situation. What is especially important is that we take care of ourselves and then decide how to most effectively respond. This list is not intended to be all-inclusive and is in no order of preference. Read the list of responses and think about the discussion questions at the end of the list.

Leave: We physically remove ourselves from the situation that activates us.

Avoidance: We avoid future encounters with and withdraw emotionally from people or situations that activate us.

Silence: We do not respond to the situation that activates us even though we feel upset by it. We endure the situation without saying or doing anything.

Release: We notice what activates us, but we do not take it in. We choose to let it go. We do not feel the need to respond.

Attack: We respond with an intention to hurt or offend whoever has activated us.

Internalization: We internalize what activates us. We believe it to be true.

Rationalization: We convince ourselves that we misinterpreted the trigger, that the intention was not to hurt us, or that we tell ourselves we are overreacting so that we can avoid saying anything about the trigger.

Confusion: We feel upset but are not clear about why we feel that way. We know we feel angry, hurt, or offended. We just don’t know what to say or do about it.

Shock: We are caught off guard, unprepared to be activated by this person or situation, and we have a difficult time responding.

Name: We identify what is upsetting us to the person or organization.

Discuss: We can invite discussion about it with the person or organization that activates us.

Confront: We name what activates us and demand that the offending behavior or policy be changed.

Surprise: We respond to the activation in an unexpected way. For example, we react with constructive humor that names what activated us but makes people laugh.

Strategize: We work with others to develop a programmatic or political intervention to address the activations in a larger context.

Misinterpretation: We are feeling on guard and expect to be triggered so that we misinterpret something someone says and are triggered by our misinterpretation rather than by what they actually said.

Discretion: Because of dynamics in the situation (power differences, risk of physical violence or retribution, for example), we decide that it is not in our best interests to respond at that time, but choose to address the activation in some other way at another time.

Discussion Questions

- Think of a time when you were activated or had a strong emotional response to someone or something someone said or didn’t say.

- How did you respond? Which responses are most typical for you when you are activated? As a targeted group member? As an advantaged group member?

- Are there differences in how you respond to activations depending on the ism?

- Which responses would you like to add to your repertoire?

- Which responses do you use now and would like to stop using or use more selectively?

- What blocks you from responding to activations in ways that feel more effective?

- What can you do to expand your response repertoire?

Recommended Materials/Readings for Students: What you might share with participants before and/or after activity to augment it (optional)

Hunter, D. (2009). Facilitating yourself. The art of facilitation (pp. 46-53). Jossey-Bass.

Obear, K. (2013). Navigating triggering events: Critical competencies for social justice educators. In L. M.Landreman (Ed.), The art of effective facilitation: Reflections from social justice educators (pp. 151-172).Stylus Publishing.

Recommended Supplementary Materials/Readings for the Facilitator: What facilitators should read, in addition to your chapter, before facilitating this activity (optional)

Bell, L.A., Goodman, D., & Varghese, R. (2016). Critical self-knowledge for social justice educators. In M. Adams, & L. A. Bell, (Eds.), Teaching for diversity and social justice (3rd ed., pp. 397- 418). Routledge.

Hunter, D. (2009). Facilitating yourself. The art of facilitation (pp. 46-53). Jossey-Bass.

Obear, K. (2013). Navigating triggering events: Critical competencies for social justice educators. In L. M. Landreman (Ed.), The art of effective facilitation: Reflections from social justice educators (pp. 151-172). Stylus Publishing.

Name(s) to credit for this activity

- Rani Varghese (2021) adapted from

- Obear, K. (2013). Navigating triggering events: Critical competencies for social justice educators. In L. M. Landreman (Ed.), The art of effective facilitation: Reflections from social justice educators (pp. 151-172). Stylus Publishing, and

- Hardiman, R., Jackson, B., & Griffin, P. (2007). Conceptual foundations for social justice education. In M. Adams, L. A. Bell, & P. Griffin (Eds.), Teaching for diversity and social justice (2nd ed., pp. 35–66). Routledge.

SJE Approach

Name of Activity: SJE Approach, Option A: Interactive Lecture Slide Show, Quadrant 1 in Chapter 4

Instructional Purpose Category:

- Exploring institutional-level oppression

- Exploring individual/interpersonal-level oppression

- Exploring cultural- or societal-level oppression

- Exploring internalized oppression, internalized messages, or implicit bias

- Exploring history

- Exploring liberation and social action

14. Terminology /exploring language

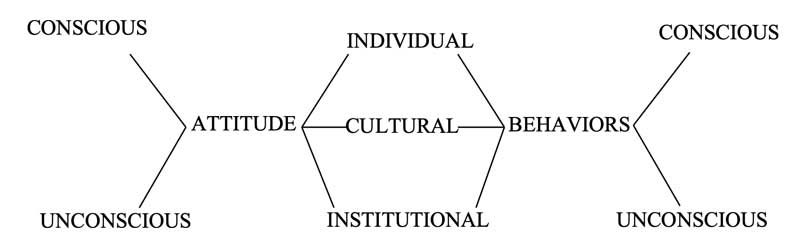

Instructional Purpose: The purpose of this activity is for the instructors/facilitators to deliver an interactive lecture about the social justice education (SJE) approach to oppression and its manifestations at personal, institutional, societal, and cultural levels. They draw from the core concepts presented in Chapter 4 and from the slide show available on the website. The slide show provides illustrative materials (visuals) that will help the instructor prepare for lecture presentations. However, we advise instructors to not rely on the slide show to organize the lecture but instead to select specific slides and materials that they need. Please note that this slide show does not correspond precisely with the content, or the sequence of core concepts presented in Chapter 4.

Learning Outcomes: Participants will be able to understand a SJE approach to oppression and its manifestations at the persona, institutional, societal, and cultural levels.

Time Needed: 30-40 minutes

Materials Needed: Digital link to slide show

Degree of Risk: Low-risk

Procedure1: Create/adapt the content of the slides using the content in Chapter 4 and the slide show available on the website; identify places where pair-shares could be infused into your lecture presentation.

Facilitation Notes & Considerations: There are activities to apply some of the core concepts in the Quadrant 2 and Quadrant 3 activities. The facilitators will need to briefly recap key talking points before or after interactive activities. Depending on participants’ needs, it may be helpful to make the slides and notes available.

Recommended Materials/Readings for Participants:

Adams, M., Zúñiga, X., (2018). Core Concepts for Social Justice Education. Readings for Diversity in Social Justice. In Adams, M., Blumenfeld, W.J., Catalano, D. C. J., DeJong, K., Hackman, H.W., Hopkins, L.e., Love, B.J., Peters, M. L., Shlasko, D., Zúñiga, X., (4th ed., pp. 41 – 49). Routledge.

Hardiman, R., Jackson, B. W., & Griffin, P. (2007). Conceptual foundations for social justice education. In M. Adams, L. A. Bell, & P. Griffin (Eds.), In Teaching for diversity and social justice (2nd ed., pp. 35–66). Routledge.

Young, I. M. (1990). The Five Faces of Oppression. Justice and the politics of difference (pp. 39–65). Princeton University Press.

Recommended Supplementary Materials/Readings for the Facilitator:

Hardiman, R., Jackson, B. W., & Griffin, P. (2007). Conceptual foundations for social justice education. In M. Adams, L. A. Bell, & P. Griffin (Eds.), Teaching for diversity and social justice (2nd ed., pp. 35–66). Routledge.

Harro, B. (2018). The cycle of socialization. In Adams, M., Blumenfeld, W.J., Catalano, D. C. J., DeJong, K., Hackman, H.W., Hopkins, L.E., Love, B.J., Peters, M. L., Shlasko, D., Zúñiga, X., Readings for Diversity in Social Justice. (4th ed., pp. 41 – 49). Routledge.

Kirk, G., & Okazawa-Rey, M. (2013). Identities and social locations: Who am I? Who are my people? In Adams, M., Blumenfeld, W.J., Catalano, D. C. J., DeJong, K., Hackman, H.W., Hopkins, L.E., Love, B.J., Peters, M. L., Shlasko, D., Zúñiga, X., Readings for Diversity in Social Justice. (4th ed., pp. 10 - 15). Routledge.

Young, I. M. (1990). The Five Faces of Oppression. Justice and the politics of difference (pp. 39–65). Princeton University Press.

Name(s) to credit for this activity

- Adapted by Maurianne Adams, Ximena Zúñiga, Rani Varghese, Nina Tissi-Gassoway, David Neely and Itza D. Martínez from:

- Pat Griffin (2007). Appendix 3I Oppression lecture slide show, Chapter 3, Conceptual foundations for social justice education. In M. Adams, L. A. Bell, & P. Griffin (Eds.), Teaching for Diversity and Social Justice (2nd ed., pp. 35-88). Routledge.

Core Concepts Slideshow

Download Now (PDF 1.8MB)1If conducting this activity on a digital platform such as Google Meet, Zoom, or other, be mindful of how the facilitator will create small breakout groups and support them (via chat or through digital access to materials).

PDF is password protected. Is this meant to embedded text or a download?

Name of Activity: Levels and Types of Oppression Interactive Lecture (Core Concepts) Supplement, Quadrant 1, Chapter 4

Instructional Purpose Category:

4. Exploring institutional-level oppression

5. Exploring individual/interpersonal-level oppression

6. Exploring cultural- or societal-level oppression

7. Exploring internalized oppression, internalized messages, or implicit bias

14. Terminology /exploring language

Instructional Purpose: The purpose of this activity is for the instructors/facilitators to deliver an interactive lecture about the social justice education (SJE) approach to oppression and its manifestations at personal, institutional, societal, and cultural levels. They draw from the core concepts presented in Chapter 4 and from the slide show available on the website. The slide show provides illustrative materials (visuals) that will help the instructor prepare for lecture presentations. However, we advise instructors to not rely on the slide show to organize the lecture but instead to select specific slides and materials that they need. Please note that this slideshow does not correspond precisely with the content, or the sequence of core concepts presented in Chapter 4.

Learning Outcomes: Participants will be able to understand some of the intersections of the levels and types of oppression.

Time Needed: 30–40 minutes

Materials Needed: Review the seven core concepts and add any additional examples that are relevant to the audience or topic.

Degree of Risk: Low-risk

Procedure1: Create/adapt the content of the slides using the content in Chapter 4 and the slide show available on the website; identify places where pair-shares could be infused into your lecture presentation.

Facilitation Notes & Considerations: There are activities to apply some of the core concepts in the Quadrant 2 and Quadrant 3 activities. The facilitators will need to briefly recap key talking points before or after interactive activities. Depending on participants’ needs, it may be helpful to make the PowerPoint slides and notes available.

Recommended Reading for Students:

Bell, L.A., (2018). Theoretical Foundations for Social Justice Education. In Adams, M., Blumenfeld, W.J., Catalano, D. C. J., DeJong, K., Hackman, H.W., Hopkins, L.E., Love, B.J., Peters, M. L., Shlasko, D., Zúñiga, X., Readings for Diversity in Social Justice. (4th ed., pp. 34 – 41). Routledge.

Hardiman, R., Jackson, B. W., & Griffin, P. (2007). Conceptual foundations for social justice education. In M. Adams, L. A. Bell, & P. Griffin (Eds.), Teaching for diversity and social justice (2nd ed., pp. 35–66). Routledge.

Young, I. M. (1990). The Five Faces of Oppression. Justice and the politics of difference (pp. 39–65). Princeton University Press.

Recommended Reading for Facilitators:

Hardiman, R., Jackson, B. W., & Griffin, P. (2007). Conceptual foundations for social justice education. In M. Adams, L. A. Bell, & P. Griffin (Eds.), Teaching for diversity and social justice (2nd ed., pp. 35–66). Routledge.

Harro, B. (2018). The cycle of socialization. In Adams, M., Blumenfeld, W.J., Catalano, D. C. J., DeJong, K., Hackman, H.W., Hopkins, L.E., Love, B.J., Peters, M. L., Shlasko, D., Zúñiga, X., Readings for Diversity in Social Justice. (4th ed., pp. 41 – 49). Routledge.

Kirk, G., & Okazawa-Rey, M. (2013). Identities and social locations: Who am I? Who are my people? In Adams, M., Blumenfeld, W.J., Catalano, D. C. J., DeJong, K., Hackman, H.W., Hopkins, L.E., Love, B.J., Peters, M. L., Shlasko, D., Zúñiga, X., Readings for Diversity in Social Justice. (4th ed., pp. 10 - 15). Routledge.

Young, I. M. (1990). The Five Faces of Oppression. Justice and the politics of difference (pp. 39–65). Princeton University Press.

Credits:

- Adapted by Maurianne Adams and Ximena Zúñiga (2021) from

- Pat Griffin (2007). Appendix 3I Oppression lecture slide show, Chapter 3, Conceptual foundations for social justice education. In M. Adams, L. A. Bell, & P. Griffin (Eds.), Teaching for diversity and social justice (2nd ed., pp. 35–88). Routledge.

Core Concepts Slideshow

Download Now (PDF 1.8MB)1If conducting this activity on a digital platform such as Google Meet, Zoom, or other, be mindful of how the facilitator will create small breakout groups and support them (via chat or through digital access to materials).

Name of Activity: SJE Approach – Option C: Five Faces of Oppression Interactive Lecture Supplement (Core Concepts) , Quadrant 1, Chapter 4.

Instructional Purpose Category:

- Exploring institutional-level oppression

- Exploring cultural- or societal-level oppression

- Exploring history

- 14. Terminology /exploring language

Instructional Purpose: Facilitators can choose to use “Levels and Types” or “Five Faces” as a framework for analysis of oppression. The “Five Faces” framework offers an interesting analysis of different types and characteristics of oppression, mainly at the societal/cultural level. The “Levels” offers a simple framework that focuses on distinctions between societal/cultural, institutional, and personal/interpersonal levels at which oppression and disadvantage take place. As an introduction to the social justice education (SJE) approach, we believe that the “Levels” is a useful beginning analytic framework but can be used in conjunction with the “Five Faces” to deepen participants’ understanding of oppression.

Learning Outcomes: Students will be able to better understand how the Five Faces of Oppression can help us analyze the complexities of oppression.

Time Needed: 10-15 minutes

Materials Needed: Slide deck or digital link to slide deck

Degree of Risk: Low-Risk

Procedure1: What follows is text and slides that can be used by the facilitator in presenting the Five Faces of Oppression. Provide a definition of oppression, referring to the slide and ask the participants to then generate their own examples of the five faces of oppression. You can provide the following examples below.

- Examples: The exploitation of black slave labor rationalized in part by “heathen” African religious practices; of women for lower wages in the workforce; of undocumented workers for substandard wages and conditions of work.

- Examples: The marginalization of denominations outside the Protestant mainstream (Amish, Jehovah’s Witnesses, Mormons, Seventh-day Adventists); of women within upper-level corporate and political structures; of domestic and agricultural (black, Latinx/e, Asian) workers in their efforts to gain union support; of disabled workers.

- Examples: The powerlessness of Japanese American people to resist or avoid forced internment during World War II; of women to avoid harassment and rape; of uneducated, immigrant workers; of disabled peoples to negotiate public buildings that do not have accommodations.

- Examples: The cultural imperialism experienced by Native Americans relocated onto reservations and forcibly “assimilated” by Christian denominational mission boarding schools; of patriarchal culture in politics and the workplace; of white middle-class approaches to learning in public schools; of norms of cognitive or physical ability.

- Examples: The violence visited upon individual Arab and South Asian Americans in the rapid acceleration of harassment and hate crimes from the mid-1970s up to and following 9/11; upon gays, lesbians, and transgender peoples in schools, on public streets or transit, in prisons; upon women in private social or domestic settings.

Facilitation Notes & Considerations: There is an activity to apply these concepts in the Quadrant 3 activities. Facilitators will need to briefly recap the lecture before the activity. Depending on the participants’ needs, it may be helpful to make the PowerPoint slides and notes available.

Recommended Materials/Readings for Students:

Young, I. M. (1990). The Five Faces of Oppression. Justice and the politics of difference (pp. 39–65). Princeton University Press.

Recommended Supplementary Materials/Readings for the Facilitator:

Young, I. M. (1990). The Five Faces of Oppression. Justice and the politics of difference (pp. 39–65). Princeton University Press.

Name(s) to credit for this activity:

- Adapted by M. Adams (2015) from Adams, M., & Joshi, K.Y. (2007). Religious oppression curriculum design (Chapter 11, Appendix 11B: Participant worksheet: Five faces of oppression). In M. Adams, L. A. Bell, & P. Griffin (Eds.), Teaching for diversity and social justice (2nd ed., pp. 255–284). Routledge.

- Young, I. M. (1990). The Five Faces of Oppression. Justice and the politics of difference (pp. 39–65). Princeton University Press.

1If conducting this activity on a digital platform such as Google Meet, Zoom, or other, be mindful of how the facilitator will create small breakout groups and support them (via chat or through digital access to materials).

5 Faces of Oppression

Download Now (PDF 323KB)Closing Activity

Name of Activity: Closing Activity (Core Concepts), Quadrant 1, Chapter 4

Instructional Purpose Category:

- Icebreakers

- Tone setting / developing group guidelines

Instructional Purpose: The purpose of this activity is to bring a component of the session to a close before transitioning to a different component or topic, taking a break, or ending a session.

Learning Outcomes:Participants will be able to understand how to transition between and in a session.

Time Needed: 5-10 minutes

Materials Needed: None

Degree of Risk: Varies depending on session and group

Procedure1: Thank the participants for their engagement, participation, risk-taking, and sharing during the session or activity. Explain that the group will be doing a brief closing round where everyone is invited to share before closing the space. Use one of the following prompts or create your own:

- Share one feeling or thought about today’s session/activity.

- Pose one question you will continue to think about.

- Name one thing you learned that really touched you or made you think.

- Say one thing you appreciate about the group or workshop.

Advise the participants to speak openly, since this encourages active listening and reflection. Prompt the participants to share in round-robin style or by going around the circle in order, depending on preference and time. The participants may “pass” until the rest of the group has shared if they need more time to think. The facilitator is advised to participate in the closing round and may role model by sharing first if there are no volunteers.

Facilitation Notes & Considerations: While these share-outs are meant to serve as a closing round, the participants may share meaningful and profound information. Due to time limitations, the group may not have time to process or debrief what is shared. In this situation, the facilitator may want to thank the participants for their openness and acknowledge the value of what was shared. If necessary, the facilitator may check in one-on-one with the participants who bring up anything of immediate concern. The facilitator may also use any information from the closing round to frame the next activity or session.

Recommended Materials/Readings for Students: None

Recommended Supplementary Materials/Readings for the Facilitator:

brown, a.m. (2021). Holding Change The way of emergent strategy facilitation and mediation. A.K. Press.

Lakey, G. (2020). Facilitating Group Learning: Strategies for success with adult learners. (2nd edition). PM Press.

Name(s) to credit for this activity

- Adapted by Itza D. Martínez & Ximena Zúñiga (2021) from:

- McDonald, J., and Zúñiga, X. (2015). Closing Activity. Teaching for diversity and social justice companion website. (3rd., ed.). Routledge.

- Zúñiga, X. (2021) EDUC 202: Exploring social/cultural difference and commonalities intergroup dialogue curriculum. Social Justice Education, University of Massachusetts Amherst.

1If conducting this activity on a digital platform such as Google Meet, Zoom, or other, be mindful of how the facilitator will create small breakout groups and support them (via chat or through digital access to materials).

Quadrant 2

Check-In and Revisiting Guidelines

Name of Activity:Check-In and Revisiting Guidelines (Core Concepts), Quadrant 2 in Chapter 4

Instructional Purpose Category:

- Icebreakers

- Tone setting / developing group guidelines

Instructional Purpose:The purpose of this activity is to bring participants back into the space and assess the group process thus far.

Learning Outcomes:After this activity participants will be reoriented to the space they are co-creating for learning and review guidelines, practice discussing guidelines – what they look and sound like for the learning space.

Time Needed:10-20 minutes

Materials Needed: Newsprint, Slide, or other digital platform with pre-existing guidelines

Degree of Risk: Low-risk

Procedure: Welcome the participants back into the space as they enter the room. Once everyone is seated, greet the group and review the agenda and goals for the session. Next, explain to the participants that the session will begin by doing a brief process check to reflect on how they are feeling about the group dynamics and their participation. Direct the participants’ attention to the group guidelines created previously. If time allows, ask the participants to read the guidelines aloud one at a time, either as a read-around or popcorn style. Invite them to partner up and do a speak-and-listen activity using the guidelines to reflect on:

- Something related to the guidelines that is going well for them personally,

- Something they could improve on related to the guidelines.

Give each partner three minutes to share without interruption.1

After six minutes, invite the group back together. Debrief the speak-and-listen activity:

- Would anyone like to share what they discussed?

- What is going well?

- What could be improved on?

- What adjustments, if any, should the group make moving forward?

Note any changes in the guidelines newsprint and thank the group for their participation.

Facilitation Notes & Considerations: Remind the participants to speak from their own experience when sharing with the larger group and to ask permission before sharing someone else’s story. Depending on the group and their dynamics, this could be a brief check-in or a longer discussion. Depending on if the activity is being done on a digital platform such as Google Meet or Zoom, facilitators will need to set up break-out meeting rooms for dyads for the pair-share once everyone has joined.

Recommended Materials/Readings for Students: None

Recommended Supplementary Materials/Readings for the Facilitator: None

Name(s) to credit for this activity:

- Updated by Itza D. Martínez & Ximena Zúñiga (2021) from:

- Adapted by McDonald, J., and Zúñiga, X., (2015). Check-In and Revisiting Guidelines. Teaching for diversity and social justice companion website. (3rd., ed.). Routledge.

- Zúñiga, X. (2015; 2021). EDUC 202: Exploring social/cultural difference and commonalities intergroup dialogue curriculum. Social Justice Education, University of Massachusetts Amherst.

1If conducting this process online, small groups can be via breakout rooms and prompts made available via chat.

Cycle of Socialization

Name of Activity: Cycle of Socialization, Option A: Lecture Presentation for Quadrant 2, Chapter 4

Instructional Purpose Category:

- Early learning / socializations

- Exploring internalized oppression, internalized messages, or implicit bias

14. Terminology /exploring language

Instructional Purpose: The purpose of this activity is to introduce participants to the concept of socialization as a framework for understanding privilege and oppression in our lives.

Learning Outcomes: After this activity participants will have language and an understanding of Bobbie Harro’s Cycle of Socialization.

Time Needed: 25-30 minutes

Materials Needed: Handouts/Links of Harro’s Cycle of Socialization figure and slides from the SJE Approach presentation available on the website.

Degree of Risk: Low risk

Procedure: The participants should read, as an assigned homework reading assignment, Bobbie Harro’s “The Cycle of Socialization” (see recommended readings below). Acknowledge that this was a part of their assigned readings and explain that the group will be reviewing it together because it is a core concept for the session. Explain that the facilitators will be using personal stories from targeted and privileged perspectives to help illustrate how we are impacted by and respond to different events in our lives. The facilitators pass out the Cycle of Socialization handout and guide participants through it using personal examples. Facilitators are encouraged to share examples that not only relate directly to their session topic (racism, transgender oppression, etc.) but that also reference interactions or events that may help illustrate intersections with other dynamics of privilege and oppression (e.g., ableism, adultism, etc.) from both targeted and a privileged social group perspective. Having a range of examples normalizes that we all may have experienced oppression and privilege in our lives, regardless of our current status in systems of advantage and disadvantage.

Facilitation Notes & Considerations: In selecting their examples, facilitators should try to balance conscious as well as unconscious aspects of the cycle. Use concrete examples from everyday life, relevant to both privileged and targeted groups. The presentation of the Cycle of Socialization becomes tangible and real for the participants when the facilitators work together by co-presenting the main points and sharing personal stories from their own lives. If there is enough time, invite participants to share stories and give examples from their own lives.

As the facilitators model their stories, they should review the terminology that is relevant to their identities as a way to integrate the terminology without “teaching” the terms. Revisiting terms such as “advantaged/privileged,” “disadvantaged/subordinated,” and “salient” might be useful.

Recommended Materials/Readings for Participants:

Harro, B. (2018). The cycle of socialization. In M. Adams, W. Blumenfeld, D. C. J. Catalano, K. “S”. DeJong, H.W. Hackman, L.E. Hopkins, B.J. Love, M. L. Peters, D. Shlasko, & X. Zúñiga (Eds.), Readings for diversity and social justice (4th ed., pp. 27 - 34). Routledge.

Recommended Supplementary Materials/Readings for the Facilitator:

Harro, B. (2018). The cycle of socialization. In M. Adams, W. Blumenfeld, D. C. J. Catalano, K. “S”. DeJong, H.W. Hackman, L.E. Hopkins, B.J. Love, M. L. Peters, D. Shlasko, & X. Zúñiga (Eds.), Readings for diversity and social justice (4th ed., pp. 27 - 34). Routledge.

.

Name(s) to credit for this activity

- Hardiman, R., Jackson, B., & Griffin, P. (2007). Conceptual foundations for social justice education (Chapter 3, Handout 3E). In M. Adams, L. A. Bell, & P. Griffin (Eds.), Teaching for diversity and social justice (2nd ed., pp. 35–66). Routledge.

- Harro, B. (2000). The cycle of socialization. In M. Adams, W. J. Blumenfeld, R. Castañeda, H. W. Hackman, M. L. Peters, & X. Zúñiga (Eds.), Readings for diversity and social justice (pp. 15–21). Routledge.

- Zúñiga, X. (2021; 2015). EDUC 202: Exploring social/cultural difference and commonalities intergroup dialogue curriculum. Social Justice Education, University of Massachusetts Amherst.

Slideshow not supplied.

Name of Activity: Cycle of Socialization, Option B: Activity for Quadrant 2, Chapter 4

Instructional Purpose Category:

- Early learning / socializations

- Exploring internalized oppression, internalized messages, or implicit bias

14. Terminology /exploring language

Instructional Purpose: The purpose of this activity is to introduce participants to the concept of socialization as a framework for understanding privilege and oppression in our lives.

Learning Outcomes: After this activity participants will have language and an understanding of Bobbie Harro’s Cycle of Socialization.

Time Needed: 25-30 minutes

Materials Needed: handouts and/or a digital link to document of Harro’s Cycle of Socialization figure; newsprint and markers or link to a digital platform for participants to write on, such as a set of slides, digital whiteboard, Jamboard or Padlet.

Degree of Risk: Low-risk

Procedure: Have the participants get into four equal-sized groups (predetermined mixed identity if possible). Assign each group a portion of the cycle: First socialization, institutional and cultural socialization, enforcements, and results. Instruct the participants to take 10 minutes in small groups to review their stage of the cycle and brainstorm some examples of how they were trained to “fit in” their assigned roles during a particular stage of the cycle. Have the group choose a recorder and reporter. Write examples on newsprint (or another digital platform such as a slide/digital whiteboard/Jamboard/Padlet). One member from each group takes one or two minutes to report out to the large group some of their experiences and insights from their discussions. A large-group debriefing should allow the participants to think about their socialization process within the context of the cycle. The facilitators should focus on similarities and differences of how people were socialized. Discuss as a group the last stage of the socialization process and how change is created. The facilitators might want to indicate that the group will dedicate more time to talking about planning and taking action later in the course or workshop.

Facilitation Notes & Considerations: If possible, determine groups beforehand so that they have a variety of social identities in each group.Be sure to include or highlight examples that highlight collusion or ways that we resist oppression. Also be mindful to highlight intersectionality in examples. Remind the participants that most of us have experienced both oppression and privilege depending on our social identities, and that some of these statuses [identities] (class, age, ability) can change over time.

Recommended Materials/Readings for Participants:

Harro, B. (2018). The cycle of socialization. In M. Adams, W. Blumenfeld, D. C. J. Catalano, K. “S”. DeJong, H.W. Hackman, L.E. Hopkins, B.J. Love, M. L. Peters, D. Shlasko, & X. Zúñiga (Eds.), Readings for diversity and social justice (4th ed., pp. 27–34). Routledge.

Recommended Supplementary Materials/Readings for the Facilitator:

Harro, B. (2018). The cycle of socialization. In M. Adams, W. Blumenfeld, D. C. J. Catalano, K. “S”. DeJong, H.W. Hackman, L.E. Hopkins, B.J. Love, M. L. Peters, D. Shlasko, & X. Zúñiga (Eds.), Readings for diversity and social justice (pp. 27 - 34). Routledge.

Name(s) to credit for this activity:

- Ximena Zúñiga & Itza D. Martínez (2021) from:

- Zúñiga, X. (2021; 2015). EDUC 202: Exploring social/cultural difference and commonalities intergroup dialogue curriculum. Social Justice Education, University of Massachusetts-Amherst.

- Harro, B. (2018). The cycle of socialization. In M. Adams, W. Blumenfeld, D. C. J. Catalano, K. “S”. DeJong, H.W. Hackman, L.E. Hopkins, B.J. Love, M. L. Peters, D. Shlasko, & X. Zúñiga (Eds.), Readings for diversity and social justice (4th ed., pp. 27 - 34). Routledge.

Name of Handout:Cycle of Socialization