Chapter 12 - Managing choices and decisions

Download All Figures and TablesNote Click the tabs to toggle content

The change balloon

This approach offers a way to visualise the priorities in a complex decision. It is particularly useful when the client has multiple factors to consider in making a choice, but is struggling to prioritise them.

As a coach, you can:

- Ask the coachee to write down their wish list. This may refer to a specific situation, for example what they want in their next job, or life in general.

- Draw a hot-air balloon, with a large basket. Each wish will be written on a post-it, which becomes a weight hanging on the side of the basket.

- Ask the coachee to imagine that the balloon has sprung a slow leak. One of the weights will have to be cut loose. Which can they afford to drop?

- The item is deleted and recorded elsewhere as the lowest priority from the list. One-by-one the weights are allowed to fall until only one is left.

- How does the coachee feel about the resulting priority rankings?

- Any hints that the coachee had difficulty in letting go of any of the weights can be useful to explore later.

Conjoint analysis

This is an alternative to the change balloon, for people who prefer to take a more analytic approach. It can also be used alongside the change balloon as an additional check or reinforcement of the client’s view of their priorities.

Conjoint analysis helps people prioritise between different goals, or different options generally.

Download Table

|

Salary |

Location |

Supportive Colleagues |

Work–life balance |

Benefits package |

Training |

Location |

Salary |

|

|

|

|

|

Supportive colleagues |

Salary |

Location |

|

|

|

|

Work-life balance |

Salary |

Work–life balance |

Supportive Colleagues |

|

|

|

Benefits package |

Salary |

Location |

Supportive Colleagues |

Work–life balance |

|

|

Training |

Salary |

Location |

Supportive Colleagues |

Work–life balance |

Training |

|

Job stretch |

Job stretch |

Job stretch |

Job stretch |

Job stretch |

Job stretch |

Job stretch |

Table 12.1 Conjoint analysis matrix: An example.

- List all the options, in whatever order they occur to the coachee. For example, what they want in their next job or in a new house, or where they can concentrate their developmental effort for the coming 12 months.

- Take some additional time to reflect if there are further options or choices to add.

- Create a matrix (see Table 12.1).

- Compare items, e.g. salary and location and choose between them – i.e. Which is more important to you? Which do you value the most? Write the choice in the relevant box.

- Compare each item with all the other items, in turn, and record which item was chosen in each comparison, ensuring all items have been compared only once with each other.

- Add the number of times each is the first preference, in this example the order of importance is job stretch (5); salary (4); location and supportive colleagues (3); work–life balance (2); training (1).

- If appropriate repeat the exercise, using a different criterion of selection (e.g. If the first selection was by what you value, the second could be what you think another stake holder would value)

- Verify if:

- It makes your choices clearer.

- The results match your instincts.

- You feel motivated to act upon these insights.

Extremes

This technique emerged from helping clients tackle situations which were complex in terms of values conflict – in particular, when they feel they are being pushed towards a behaviour or decision that doesn’t feel right (i.e. are experiencing a level of cognitive dissonance).

As a coach, you can:

- Describe briefly the issue and the circumstances around it.

- Help the coachee define a spectrum, on which the dilemma sits. Typically questions here are:

- What do you think you need to change from, to?

- How do you want circumstances to be different?

- Invite the coachee to identify extreme ends of the spectrum. You and the coachee can then assign an emotive label to each of these extreme situations. Questions at this stage might be:

- Where are you on this spectrum now? (How have you dealt with it so far?)

- Where do you think you should be?

- Who says this is where you should be? Your inner self? Colleagues/your boss? The customer?

- What are the consequences of remaining where you are on the spectrum?

- What are the consequences of moving to the new position?

- Is there a position which you would be more likely to commit to and to stick to?

- Consider the best way to deal with the situation by exploring these two extremes.

Letting go using situational models

Here we add to the visual element a physical (kinaesthetic) aspect.

- Select a pile of different size rocks.

- Select rocks from the pile which represent the different presenting issues – the weight of the rocks indicating the current importance of the issue.

- Write on the rock what it represents (all the rocks are varnished with a ‘wipe clean surface’ so they can be written on in a water soluble pen).

- Place the rocks in a backpack and put on the backpack.

- After feeling the weight load, empty out the rocks and consider how you could lighten your load by resolving and letting go of some of the issues/rocks.

Call your future self

Tacit, intuitive knowledge about difficult decisions can often be accessed by imagining oneself in the future. We have already addressed this to some extent in Part II Chapter 7, under ‘visioning’, but here we ask the client to enter more deeply into a role play. A simple way of starting is to ask the client, ‘If you were to call your future self (you five or ten years from now) and ask them about this, what would they say?’

For coaches this can be more than just a powerful question to stimulate the coachee to reflect on. Actually having the conversation can potentially achieve even more. There are lots of ways to do this, but here are two:

As a coach, you will need to:

- Ask the coachee to take out their mobile phone, but keep it switched off. When they put the phone to their left ear, they are in the persona of their current self; when they use the right ear, they are their future self. (An alternative is to swap chairs, but shifting hands makes for smoother transitions!)

- Ask them what questions they would like to ask their future self, if only they had the opportunity. Don’t worry if they start off with one or two flippant questions (such as “Who will win the Derby/World Cup next year?”) – this can for some people be a necessary step in getting into persona. Capture these and explore what value would come from having an answer to each question. Now ask them to become their future self:

- How would they view these questions?

- What answers would they give?

- What single piece of advice would they offer?

- What critical question would the future self want to pose to the current self?

In both methods, it can be helpful to allow the conversations to come to a natural pause (for example, when there seems to be nothing more to say). Offer the chance for a few moments quiet reflection. With the benefit of hindsight, would they like to rethink the questions they might ask their future self? If so, repeat the exercise.

Conclude by asking them:

- What has changed for you?

- What have you realised about your current and future selves?

- What could you do to bring them more closely together and is this something you would want to do?

- And, if you and they are feeling particularly open and reflexive:

- In what ways, if any, has your future self become wiser?

Are you feeling lucky?

Exploring the concept of luck can help people change perspective about how much they can influence better outcomes to problems they face. The axiom, ‘you make your own luck’ provides an opportunity to reframe the issue in ways that encourage the coachee to take greater responsibility for outcomes and to be more creative in thinking about alternative solutions.

The following questions help the coachee consider luck:

- How much do you think the outcome depends on luck here?

- How lucky do you feel compared to the other players?

- To what extent do you think feeling unlucky is affecting how you approach this issue (e.g. your confidence levels)?

- Would you behave differently if you felt lucky?

- What’s the difference between the luckiest players and you?

- What could you do to make yourself luckier?

- What, if any, are the down sides of playing and not winning?

- How will you feel, if you do win?

The realisation that even pessimists can make their own luck often initiates a discussion about how much the individual wants to achieve a goal and how they can increase the chances of a lucky break occurring.

If the problem appears insoluble

If a problem seems insoluble to the coachee, ask them to use their imagination to answer the questions below:

- If you did have a solution, what would it look like? (But don’t use this routinely – it can be very irritating if over-used!)

- Choosing different characters from history, film or literature, how would each of them tackle this problem? What can you learn from their approaches?

- What solutions have you been avoiding? Sometimes we just don’t want to admit that a solution is readily available because it means facing up to other issues which we don’t want to acknowledge.

- Breaking the issue into chunks and exploring potential solutions to each. Do solutions for some or all of the parts suggest a solution for the whole?

- Exploring the opposites. Draw a process map of the problem. What would happen if you tackled every step in completely the opposite way to what you do now?

- Redefine the problem as a series of opportunities. What’s the silver lining in each aspect of this situation?

- If your coachee still doesn’t like any of the solutions on offer, you can help them to:

- Keep looking for an alternative. Does this problem have to be solved now? Is there a valid argument for allowing a solution to develop of its own accord? One of the most common outcomes of a learning conversation is that the coachee’s mind becomes open to a wider range of different solutions. As a result, they tend to notice possibilities that would otherwise have passed their attention by.

- Accept the least worst solution. Ranking various solutions against each other identifies the solution with the least downsides. Is the coachee prepared to accept this as a means of moving on and dealing with other, more important issues?

- Accept that they will just have to live with the problem.

- Think about how they could move out of the situation?

- Think about what changes they would have to make to themselves, their attitudes, their behaviour or their assumptions to get a new perspective on the situation?

Helping stuck clients become more creative

When someone says they are not very creative, it’s usually a self-limiting belief. It’s just that their sense of being creative has been knocked out of them in the process of education and adjusting to the expectations of the workplace. We’ve used many ways to help clients regain their creative instincts, from writing limericks to engaging in improv. The following are ideas you can share with a client to give them a wider range of options.

- Capturing: Note down ideas as they occur to you, without judgement or criticism. For example, spend a few minutes early every morning just writing about anything that comes to mind. The mind’s internal censor normally kills promising ideas because they don’t fit our existing perspective, but free writing bypasses this censor.

- Challenging: Finding tough problems to chew over will promote new approaches and perspectives.

- Broadening: Developing interests in lots of different areas which need not be closely connected. The more interesting knowledge you acquire, the more connections you perceive with problems that you want to solve. For example, plan an ‘adventure’ once a week.

- Surrounding: Making the physical and social environments more stimulating. For example, finding interesting places such as art galleries or museums to do some quiet thinking, or having conversations with people who have very different perspectives to yours.

Decision making

Individuals and teams alike tend not to have a very clear idea of how they make decisions. We tend to think that our decisions are much more rational than is the case (we tend to jump to instinctive conclusions, based on readily accessible knowledge, then rationalise them). Daniel Kahnemann’s theories of level one and level two thinking are must reads for any coach working with clients, whose decisions impact the lives of others or the fortunes of a company! Coaches can help their coachees develop better decision-making habits by working with them to:

- Revisit decisions, unpicking the process and the assumptions the coachees have made, or be more aware of the assumptions and biases in decisions to be made.

Useful questions to help the coachee consider include:

- What assumptions did they make in reaching this decision?

- Who might have been able to offer a different set of assumptions? How valid have these been?

- What did they want the answer to have been?

- How did they assess the evidence? (What weight did you give to various sources and why?)

- What outcomes might they expect from the opposite direction?

- Develop together the counter argument to the decision taken. This may result in modification of the decision, or of the rationale behind it.

- The coachee can make a new decision based on the thoughts you have unpicked.

Decision-making processes have six critical steps:

- Purpose: Why do we need to make a decision about this and why now?

- Awareness: How well do we understand this issue and its context? What assumptions are we making that might limit the options we consider?

- Definition: How precise can we be in describing the issue? Is it really one issue or several interlinked ones?

- Creative thinking: What options can we generate? What didn’t work before, but might work now? What if we did the opposite to what we have always done?

- Choosing between alternatives: How can we be sure that we are applying the same weightings in valuing alternatives? What biases should we be aware of in how we select?

- Implementing: Do we have the resources and energy to implement? Who needs to be engaged in thinking about implementation? How will we ensure they understand the decision emotionally as well as rationally? Who has what role in implementation? Is there a robust link between the macro-decision (usually by executives) and the micro-decisions (making it work, usually by people much lower down)?

For, against, interesting, instinct

This simple process helps ensure that the coachee sees an idea or proposal from several perspectives and doesn’t jump to instinctive conclusions. It stimulates a breadth of dialogue and creativity. The art is to generate as many points as possible to go under each of these headings in Table 12.2. Once all the thoughts have been combined, they provide a rich resource for an informed dialogue.

Download TableFor |

Against |

Interesting |

Instinct |

|

|

|

|

Table 12.2 For, against, interesting, instinct.

- Ask the coachee to consider the decision they need to make.

- For refers to the potential benefits of the idea.

- Against refers to the possible downsides.

- Interesting is an opportunity to capture aspects of the idea that don’t necessarily belong to ‘for’ or ‘against’.

- Instinct captures how you feel about the idea and the issues generated in the other columns.

- Help them generate as many points as possible to go under each of the headings.

- Once they have filled in the table, it will act as a rich source of information for an informed dialogue.

The free imaginative variation technique

The free imaginative variation technique is an effective alternative to the ‘come up with lots of options to reach your goal’ in the GROW model of coaching. This technique can therefore be employed to generate different ideas.

The technique can be applied to many different tasks.

Exploring your dream career

- Ask the coachee to write their ‘dream’ CV, populated with future job roles and qualifications.

- Ask them ‘what can you change or leave out whilst still preserving your “dream CV”?’. They can actively experiment by changing and deleting skills, roles, companies and qualifications (this is the ‘free imaginative variation’) until they have a clear picture of the core items that must be present for their CV to be ‘ideal’.

- Once this is established, the coach can then help the coachee break down these goals into smaller steps and find practical ways to attain them.

Maximising the value of your role

- Ask the coachee to write a ‘dream’ job description and person specification. The coachee can either add to their existing job specification document (although these tend to become quickly out of date!) or generate their own. The coachee should generate a job description that is as far-reaching as possible, incorporating all the elements that their job could entail, however ‘off the wall’.

- Think about what attributes are required for the job description, and these should be noted in a separate ‘Person Specification’ column (see example in Table 12.3). The coachee should not be worried if they do not have these attributes or skills – at the moment this is a creative exercise.

- The coachee and coach use the ‘dream job description’ as a springboard to explore how their role can be developed. The coachee explores what items they are not currently doing and whether this is something that they would like to add to their role. The coach can ask these questions:

- What skills would you need to do this new item?

- What value would it add to your organisation and to you?

- What’s stopping you doing this at the moment?

- Do you need permission from someone in order to do it?

- How do you think your line manager would react if you propose that you should do it?

- How can you take the next steps to do this item?

It is possible that the coachee identifies some elements that they could be doing, but decide they do not want to. Maybe it doesn’t play to their strengths and they do not have an interest in developing it. If this is the case, it may be proposed as a strategic idea for the team, i.e. it is a good idea, but someone else may want to or feel more comfortable doing it. Alternatively, maybe some of the items don’t add value to the business in which case they can either be discarded or reformed so that they do.

- The job description can now be edited to incorporate the coachee’s new ideas.

- Ask the coachee ‘what can you change or leave out whilst still preserving your “ideal job description”?’. They can actively experiment by changing and deleting skills and roles until they have a clear picture of the core items that must be present for their job description to be ‘ideal’.

- The coach can then help the coachee work out how to make these roles a reality, such as how to negotiate these with their boss.

- Building on the fact that both job descriptions and people evolve, asking these follow-up questions can be useful, either within the session or as an assignment to bring to the next session:

- How might this role be expected to evolve in the next 12 and 36 months?

- What changes can we predict in the expectations of stakeholders over the next 12 and 36 months?

- What measures will define success in this role now, and in 12 and 36 months?

This will allow the coachee to understand that it is normal and healthy for job roles to change and to be alert to the shifting environment and how this may affect their role. This can help reduce anxiety as change is cast as inevitable, but potentially liberating – as an opportunity for development.

Table 12.3: Example of dream job description and person specification

Download TableJob roles |

Person specification |

Write award bids

|

|

Pursue grant funding opportunities |

|

Develop relationships and partnerships with similar organisations to consider ways to:

|

|

Review operations systems and consider improvements to maximise team efficiency, e.g.

|

|

Busy fool syndrome

Feeling indispensible is a powerful addiction – many managers find it hard to focus on their own work, because they are too busy doing tasks that would be done equally well or better by their direct reports. A classic coaching question is: ‘Whose jobs are you doing in addition to your own?’

Another manifestation of busy fool syndrome (trying to do so much that you achieve too little) is when a client fills their day with avoidance tasks – things that take their attention away from issues that are more important but difficult or painful to think about.

Here are some ways to help managers recognise they have a problem, so that you can work together to find strategies to overcome it

The coach discusses with the coachee what the elements of their role are that:

- Have the greatest potential to add value.

- Enable direct reports to achieve more.

- Deliver longer-term, sustainable benefits.

Consider questions such as:

- Why would you have to do this?

- Would the team achieve more if you were able to focus on more strategic issues, or simply spend more time reflecting on what it does and how?

- How much of your time do you spend doing jobs that would be better done by people who report to you?

- What tasks do you do because you enjoy them, rather than because they are important?

- What important issues or tasks have you put off dealing with this week?

- What mechanisms do you have for getting to grips with such issues?

- What important issues or tasks have you prevented someone else from resolving recently?

Maximiser or minimiser?

Maximisers are people who are habitually driven to make the right or best choice. At a negative extreme, they can come across to other people as ditherers, overly worried about the ‘right’ choice. Minimisers are more concerned with the utility of the decision. At a negative extreme, they may be seen as slapdash. Most of us are a little of both, depending on the situation and the importance we attach to a decision. It’s probably better to have a maximiser doing heart surgery, for example, but not when they are in the front of the queue at a customer services desk! Here is a bunch of questions to help a client work on inappropriate maximiser/minimiser behaviours.

Ask the client to consider when they are faced with wide choices, do they:

- Cut to the quick and identify ‘good enough’ solutions?

- Agonise over the ‘best solution’?

- Use context and process questions to help manage choice.

Context questions:

- Why do you have to make a choice? (What are the consequences of not doing so?)

- Who else can/should you be sharing this decision with?

- How quickly is the situation likely to change after the decision is made?

- What’s the down-side of getting it totally wrong? Partially wrong?

- How easily will you be able to forgive yourself if you make a less than perfect choice? A wrong choice?

Process questions:

- How much choice do you need to feel comfortable about this decision?

- How many criteria do you have?

- How can you reduce these criteria to a maximum of three?

- How many choices meet these three criteria?

- Does one choice stand out as clearly the overall best, based on these three criteria? If not, what other criteria can you add that would differentiate between the choices?

- Can you increase the flexibility of your choice (i.e. build in the potential for change with changing circumstance?)

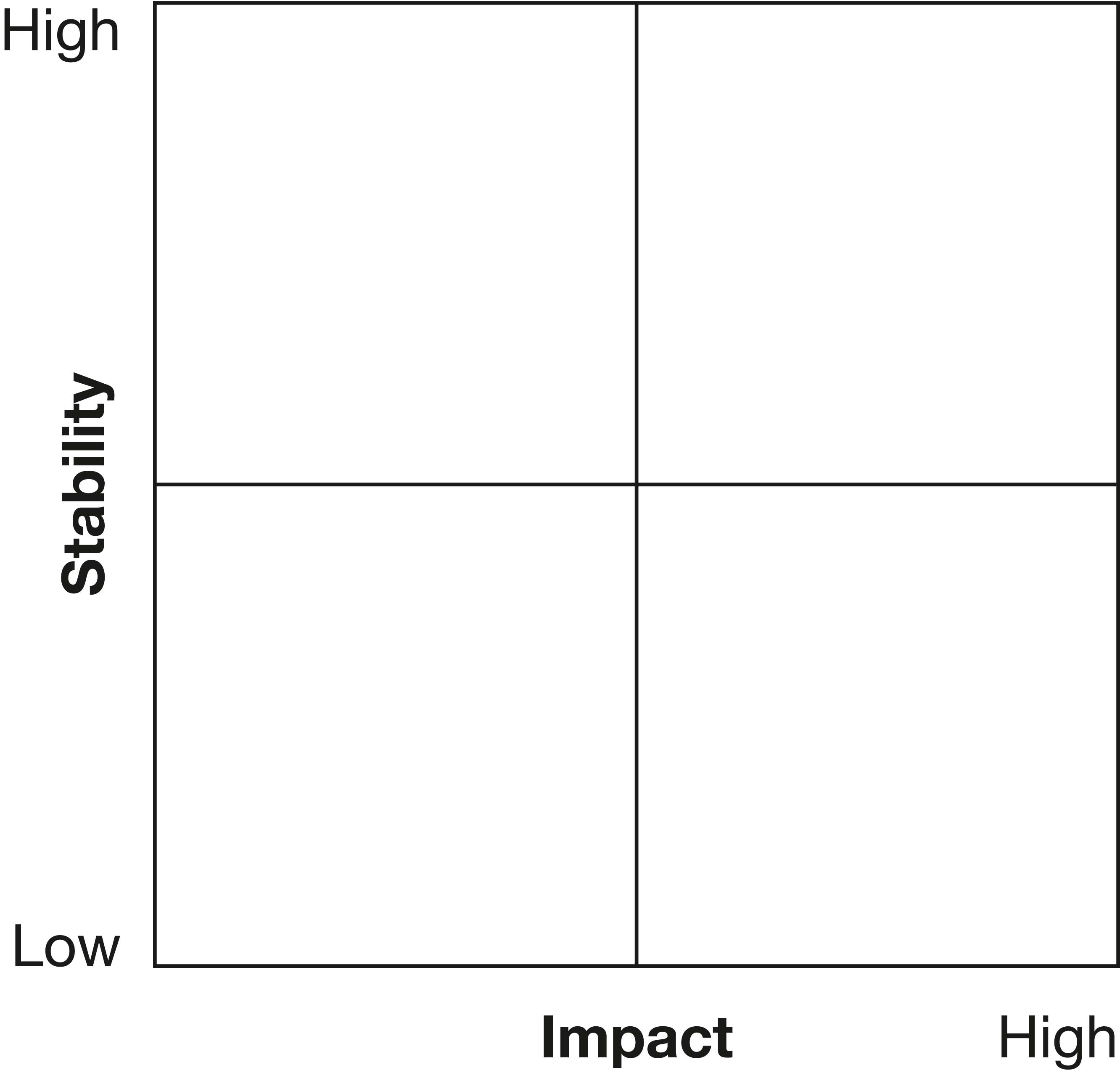

- Use the matrix in Figure 12.1 to consider stability and the impact of choices.

- Use the matrix to discuss with your coach and facilitate understanding on effective decision-making.

Consequences

Helping a client overcome ‘stuckness’ is often largely a matter of seeing things from a different perspective. This is a graphic and rapid way to capture the implications of different choices.

- Consider a decision you are pondering about.

- Complete all boxes in Table 12.4. Make the consequences of each as vivid to you as you can.

- Consider

- Have you added new perspectives as a result?

Table 12.4 Consequences matrix

Download TableWhat will happen…

|

What will happen if I do it: |

What will happen if I don’t do it: |

What will not happen… |

What will not happen if I do it: |

What will not happen if I don’t do it: |

|

…if I do it |

…if I don’t do it |

Maslow’s hierarchy of needs

There can’t be many managers who haven’t encountered the hierarchy of needs. Whether they have thought about how it applies to them is another matter. We have been surprised by how often coaches overlook this fundamental management concept as a potential tool for raising client self-awareness.

Draw up an individual’s hierarchy of needs based on the following:

- What inner drives does each of these things address?

- Which inner needs do you feel are most fully/least fully satisfied from your work?

- What strategies do you use to bridge the gap between your inner drives and what happens around you?

- In what other ways might you address those needs? (What other strategies could you adopt?)

Consider the following with the coachee:

- What do you think this hierarchy says about you?

- Are other people aware of your personal hierarchy of needs?

- How does this fit with what they need from you, or what the organisation needs from you?

- What does this tell you about the kind of job/lifestyle that would suit you best?

Ask the coachee to redraw their hierarchy presented as a triangle with chunks of each layer bitten away depending on the extent to which that need has already been met. This opens discussion of how the under-met needs might be tackled. Useful questions include:

- What prevents you from feeling fulfilled in each of these areas?

- What could you do differently to meet each of these needs?

- Do some of these needs conflict? Is it possible to make them mutually supportive?

- What compromises do you make now?

- What different compromises are you willing to make? Would you achieve a better overall picture if you did?

Using the metaphor of a roundabout

This technique is about generating a wide range of options and exploring them.

Using a sheet of flipchart paper and large pens, encourage your coachee through the following steps:

- Ask them to imagine standing at a roundabout. Get them to draw the number of possible exits (opportunities) that they consider are available to them at the moment – even the most unlikely.

- There may be a road linked to what they wanted to do when young, but their parents/carers thought this was impractical or impossible because of lack of funds or lack of ‘suitability’.

- There may be a road linked to recurring dreams or fantasies.

- There may be a road that involves them in more risk or unknown

factors than they face at present. - There may be a well-defined road, which they have been on for

some time which feels as ‘comfy as an old pair of slippers’. - There may be a road that their intuition is urging them to follow,

but which other people say is not in their interests. - Explore each possible road/exit in turn in discussion together. Metaphorically walk up each road and identify the possibilities of this route forward. Reassure your coachee that they do not need to move forward on any of the routes. It is sufficient at present to recognise that they have alternatives open to them.

- Get them to note down the positives and negatives of each potential

route. - Ask your coachee for their gut reaction to each route – a

route may feel safe or sensible but does it feel exciting? What stirs their energy? - Now get them to put a large cross at the beginning of all the roads

they don’t want to go down. - When they are left with two or more routes, develop the appropriate

number of different possible future scenarios and encourage your coachee to research each of them further. - Suggest that your coachee takes their flipchart drawing of their roundabout and puts it in a place where they can look at it frequently. Encourage them to share with their colleagues, partner or family, if appropriate, to gain their reactions and feedback.

Assessing alternatives

‘SCAMPER’ is a simple menu of creative perspectives to draw upon. It is an acronym for:

Substitute

Combine

Adapt

Maximise/Minimise

Put to other uses

Eliminate (Elaborate)

Reverse (Rearrange)

- Look at a range of possible solutions to an issue by discussing each of the SCAMPER possibilities with them.

- Discuss how to adapt ideas raised to make them work in the given context.