Chapter 7 - Setting and pursuing goals

Download All Figures and TablesNote Click the tabs to toggle content

The Boyatzis technique

Boyatzis et al. (2004) suggest that, if you ask anyone who has been most helpful to them over their career and what they do, 80 per cent of the resulting comments will be about extending dreams and reaching for new experiences.

Ask your coachee to:

- Note down a maximum of 10 people who have been helpful in their career and list briefly what they did to develop them.

- Draw their attention to the role these people played in enlarging

- their sense of ideal self and raising their horizons.

- Explore with them how the coaching relationship can follow this pattern; and what might be achieved through self-coaching.

Visioning

Visioning harnesses the power of imagination and the ability to connect the future and the present (something that few other species are able to do). The theory is that establishing this link makes us more mindful of future goals and more creative about different ways in which we might achieve them. It also, in theory, makes a much stronger connection between goals and emotions, hence deepening commitment.

Ask your coachee to:

- Close their eyes and relax, using relaxation techniques.

- Imagine him/herself as they want to be in a specified period of time. The bigger and broader the goal, in general, the longer the forward projection will be.

- Discussion of these can be used in almost any planning/decision-making processes where the outcomes will take some time to emerge.

The question set may vary, but is likely in most cases to follow a progression along these lines:

Visualisation

- Where is it that you want to be (the place)?

- Describe what you see around you – the environment, the people. How do you appear?

- What are you doing? Why?

- Describe how you feel. If you feel good, what is making you feel that way?

- Describe how the people around you feel?

- Describe what you hear?

Determination

- How is this different from now?

- How big is the gap in how you see yourself? How others see you?

- How big is the gap in how you feel? How others feel?

- How do you feel about that gap? Do you have a real desire to bridge it?

Actualisation

- What could you do to make the vision a reality?

- What's your first step?

Working back to the future

As with the previous exercise, here we are trying to establish an emotional connection with a desirable potential future scenario. This time, however, we add steps that provide a path from the present to the future.

- Create and ‘step into the future’ as you wish it to be. This involves selecting a desired state and imagining what it would feel like, look like and sound like when you are there. This should be something important, which is aligned with your personal values and is achievable, even if it is very stretching. Think about specific changes you want to bring about such as definable achievements. Put a date on this vision of the future – when will it become a reality?

- Work out the milestone actions and events that brought about this future state. Describe an action or event that will have brought it about. What will you have done to make it possible? Who else will be involved and how?

- Establish practical ways to start on the journey towards the envisioned future. How can you make each event on the journey more likely to happen than not? What can you do today to improve the probabilities?

Looking back to move forward

Here is yet another variation on the same principle.

- Create a timeline that can be expressed as a line on a sheet of paper or any other device that indicates a sense of distance.

- Mark the centre of the line as the present.

- Starting in the present, address questions such as:

- What, if anything, makes this goal unique in your experience?

- What other goals can you compare it with, which you have already achieved, in whole or part?

- Why have you chosen this goal to work on now?

- Moving to the past, address questions such as:

- When did you first become consciously aware of this goal as meaningful to you?

- How long do you think it was unconsciously lurking ready to come into awareness?

- What have you already done, in terms of thinking and preparing to progress towards this goal?

- What knowledge and skills do you already have, which will help you to achieve it?

- What experience have you acquired, which will be useful?

- What resources have you identified, which might help you?

- What barriers have you partly or wholly removed?

- What lessons have you learned/could you learn from your experience achieving similar goals in the past?

- What personal strengths have you drawn on in the past, which will be useful in pursuing this present goal?

- Now move back to the present and address questions such as:

- What does your experience of pursuing previous goals tell you about the issues you need to be aware of pursuing this one?

- What will you do better in terms of managing the goal, than you have in the past?

- When and how will you look back at your progress?

- Compared to when you started this exercise, how far along the timeline to this goal do you think you are now? Physically move the marker.

Itch, question, goal

This is a technique to help the coachee recognise and address issues which they are consciously or unconsciously choosing to ignore.

- Invite the coachee to record over a period any ‘itches’ they experience. An itch is a sense of discomfort or anxiety about some aspect of their work.

- In the next coaching session, help the coachee cluster these into a number of themes.

- For each theme, invite the coachee to develop a number of questions – for example, ‘What’s making our customers feel this way?’, or ‘What am I noticing and not noticing about this issue?’

- Next, the coachee clusters the questions and seeks to find deeper/better questions. Then they consider ‘What would I have to do to answer that question?’

- Finally, the coachee extracts one or more goals relating to the issues identified.

In addition to bringing unrecognised issues to the surface, this approach provides a balance of ‘bottom up’ goals that link to ‘top down’ goals.

The cascade of change

This model recognises that people go through a number of steps to achieve commitment, and then several more to move from commitment to achievement (see Figure 7.1).

Download Figure

As a coach, you will need to:

- See where they have reached in the various stages.

- Discuss how they can move up the ladder.

- Use feedback and those around you to ensure they are reaching achievement and awareness. Your role will be most effective when the coachee has at least reached the awareness stage.

Note:

Awareness of a requirement to change is unlikely of itself to stimulate action, unless the consequences of not doing so are immediate and dire. There may be intellectual understanding that it would be beneficial to be more skilled at a specific task or behaviour, but that is also true of hundreds of other tasks and behaviours – why should this one assume any sense of urgency or priority?

Understanding occurs when the need for change is brought into focus, usually by some external event, which underlines the benefits of taking action and the disadvantages of not doing so. Although the stimulus may be emotional, this is primarily an intellectual recognition and the sense of urgency can be rationalised away quite quickly.

Acceptance occurs when the emotional and intellectual senses of urgency align. The benefits of action strongly outweigh those of inaction and the person is able to focus on this issue without too much competition from other issues that demand his or her attention.

Commitment puts the seal on acceptance. It involves a promise to oneself or others, whose respect you value. It links achievement of the change goal with our sense of identity. Commitment will not deliver results without a plan of action. The plan will be of little use if it is not implemented and implementation requires positive feedback both from oneself and from others to reinforce commitment.

Becoming aware of different rhythms

Gabriel Roth (1990) maintains that there are five basic rhythms of life, which form a wave, and that these are present in everything we do (see Table 7.1). Knowledge of these rhythms can help us to become more aware of ourselves and the people we work with (Whitaker, 1996).

The Wave of Five Rhythms |

1. Flowing – Continuous graceful movement – think of a flowing river or a swirling wind. It is purposeful and co-ordinated, yet smooth and strong – focused uninterrupted work |

2. Staccato – Crisp, building and angular – a faster movement, increasing energy and getting things done – the rhythm of meeting deadlines |

3. Chaos – High energy, creative, top of the wave – encouraging thinking in random, original patterns – the rhythm of brainstorming, synergistic team work and individual creativity |

4. Lyrical – Light, expressive, laughter – the rhythm of humour and appreciation – often undervalued and under-used in organizations |

5. Moving stillness – Reflective, introspective, gentle – the rhythm of completion – 'wash-ups' at the end of projects – reflect on successes, identify what to do differently next time, drawing back to the centre |

Table 7.1 The wave of five rhythms (Whitaker adapted from Roth, 1990).

Research (Whitaker, 1996) has shown that we each tend to have a preferred rhythm/s, which can be different from the people we work with.

- Which are your preferred rhythms?

- Identify the rhythms of people you work with.

- What insights does this give you?

Establishing the current reality

Given that none of us is perfect, the choice of what to work on in terms of personal growth and improvement is endless. We often find that clients know that there are a lot of things they could work on, but can’t identify the one or two which are most important to them. In this process, we help them review and prioritise learning opportunities.

- The coach presents the coachee with a number of factors they must rate themselves on, or the coachee can come up with the factors themselves. For example:

- Being a better leader.

- Managing my reputation.

- Being a good family member.

- Job satisfaction.

- Meeting targets.

- Being more in control (of work or life).

- Being more creative.

- Having a clear conscience.

- Developing my team.

- Being happy.

- Having a clear sense of direction.

- Building my confidence.

- The coach asks the coachee to rank these factors in some way – for example, by placing them in baskets marked must do, should do, nice to do.

- The coachee selects the highest priority goals and defines more clearly what a particular goal actually means to them (i.e. achieves a greater level of precision about the desired state and how they would recognise it).

- The coachee then rates him or herself on a scale of 1–10 in terms of personal effectiveness.

- The coach now asks the coachee on each goal what a perfect score would be like for them and negotiates how much improvement they want to achieve within a given time frame.

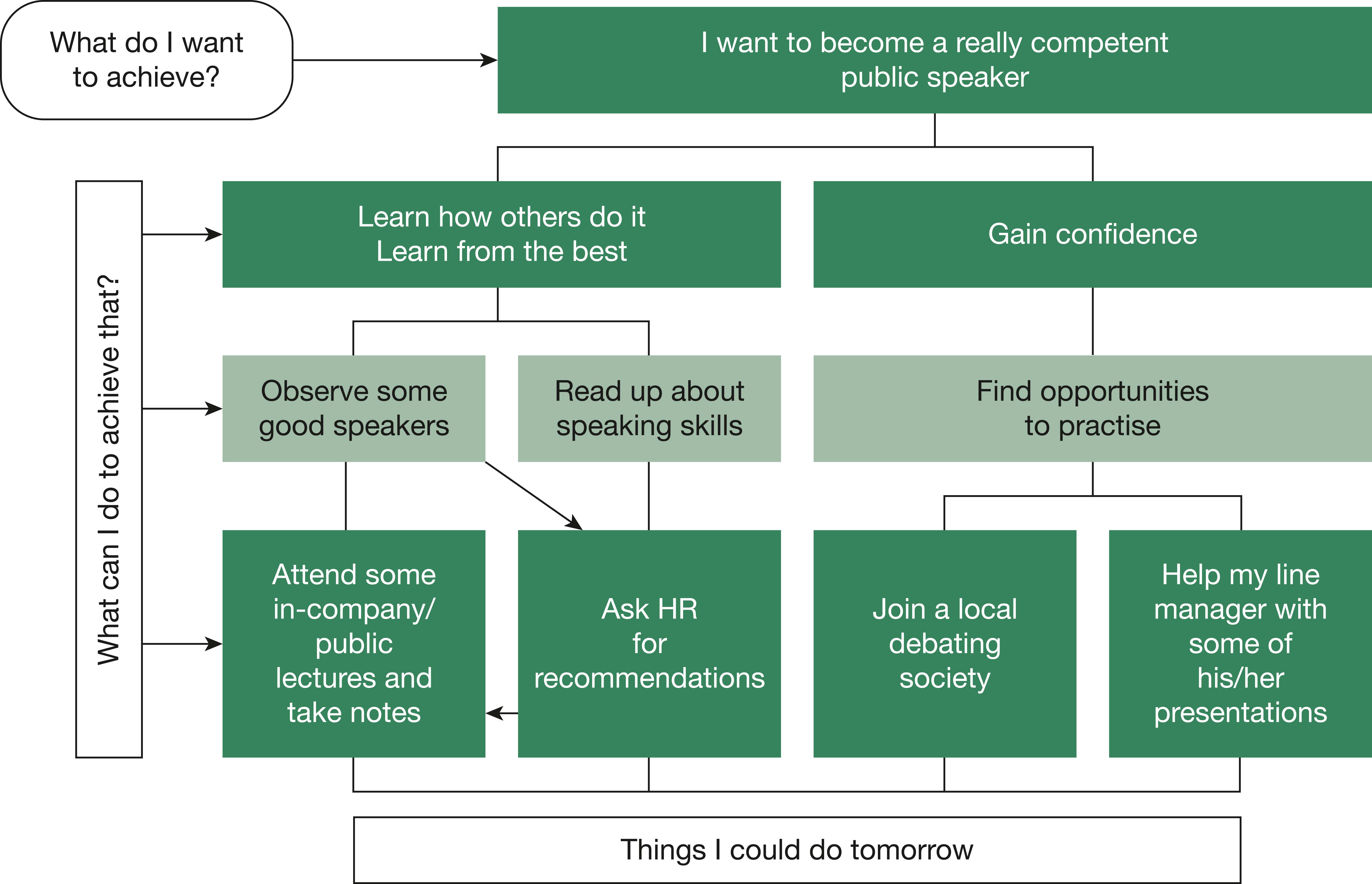

Logic trees

This is a simple approach to breaking down a complex and/or long-term goal into ‘bite-size’ chunks, which are more easily managed. It is particularly useful when:

- The client doesn’t know where to start (so does nothing)

- They need a reality check on just what may be involved in achieving their goal (and when they do work out what will be required of them, they may decide that the cost of pursuing it is too great).

Ask your coachee to:

- Define the goal as clearly as possible. Help them refine this description to no more than 10 words.

- Explore what would need to be done to achieve the goal. For example, to become a team leader, a coachee might need to demonstrate some key competencies, to make their ambition known to particular people, to build confidence among peers in their ability and to acquire more knowledge about managing others.

- Break each element of step 2 into further sub-divisions and continue the same process, layer by layer, until each results in a series of actions that could be undertaken relatively easily and/or soon.

- Begin to apply some timelines, When do they want to have achieved each of the lowest level objectives? Do they feel confident in their ability to do so? What timelines would be appropriate for the next level? Gradually work up through the process chart to the overall goal at the top.

- Step back and review the process. Does the goal now seem much more achievable than it did before? Have we missed any important elements? What milestones would it be appropriate to identify, where should we review progress and celebrate achievement so far?

- Regularly review with the coachee where they think they have reached on the flow chart. Where progress falters, help them think through the issues and develop alternative strategies.

See Figure 7.2 for a logic tree example for public speaking.

Download Figure

Setting priorities

Most coachees are intellectually aware of the urgent–important matrix, but applying the concept to how they manage their priorities is another thing!

Ask your coachee to separate urgent tasks from their most important priorities. They should focus on getting their urgent priorities dealt with. They could use the 4-D formula below:

Dump it – learn to say ‘no I choose not to do this’. Be firm.

Delegate it – hand some tasks over to others.

Defer it – defer the issue to a later time and schedule a later time to do it.

Do it – do it now if it is an important project. Don’t make excuses. Give yourself a reward for completing these projects.

Encourage them to ask themselves periodically, ‘Is what I am doing right now helping me achieve my goals?’

Some ground rules for setting goals

The following ground rules can be helpful to share with clients before deciding on goals for the coaching relationship.

- Define your most important goals for yourself (don’t use goals given to you by other people).

- Make your goals meaningful (e.g. what are the rewards and benefits you envision?).

- How specific and measurable do you want your goals to be? (SMART goals only work some of the time for some people. It may be better to establish a broad purpose and allow specific goals to emerge gradually.)

- Your goals must be flexible (don’t be so rigid that you lose good opportunities that come along).

- Your goals must be challenging and exciting (e.g. what are the 100 things you want to do in your life?).

- Your goals must be in alignment with your values (e.g. honesty, fairness, etc.).

- Your goals must be well balanced (e.g. make sure you consider spending time with your family, leisure time, etc.).

- Your goals must be realistic – but remember, there are no such things as unrealistic goals, only unrealistic time frames!

- Your goals must include contribution – you need to be a giver not just a taker.

- Your goals need to be supported.

The KISS technique

This is another simple way of prioritising actions.

Use the acronym below to help your coachee summarise their intended actions.

K – Things you should definitely KEEP doing

I – Things you should INCREASE or do more of

S – Things you should START doing that you are not doing already

S – Things you should STOP doing