Chapter 5 - Helping the coachee articulate their issues

Download All Figures and TablesNote Click the tabs to toggle content

Using metaphor to effect change

Using metaphors or stories to illustrate a particular situation can elicit different information than describing it. Exploring the commonalities and differences between the metaphor and real life can enrich the understanding of a situation.

An effective metaphor:

- Establishes parallels between the situation as the individual sees it now and a different context.

- Matches the listener’s experience, particularly at an emotional level.

- Uses strong imagery and language that captures the imagination.

- Contains clear transitions or decision points, where choices have to be made.

- Explores the impact of choices.

A practical way to use metaphor is:

- Select the metaphor. Several alternatives may be discussed before the coachee identifies one that they feel has sufficient relevance to their own situation.

- Place the coachee within the metaphor. examine their role and fill in as much of the context and background as possible, labelling other players if appropriate.

- Embed the metaphor in reality. The coach asks for examples of where and how the metaphor has been played out in real life. If some elements of these examples do not fit the metaphor, they are recorded and set aside for subsequent discussion.

- Explore the metaphor. Next, the discussion moves to how the metaphor has evolved in the past and how it might be expected to evolve in the future. Exploring the metaphor from the viewpoint of other players also enriches the understanding of the issue.

- Extract lessons from the metaphor. How does it make them feel? (Optimistic or pessimistic? Challenged or bored?) What aspects of the metaphor have the greatest impact on their work and/or life? What elements of the metaphor would they like to change?

- The coach can then work through the cycle with them again, until they have a clearer perception of the new metaphor and the role they aim to play within it.

All the world’s a stage

Humans are designed to respond to drama at a far deeper level than simply by reading words. The stories behind dramas link to some of our deepest emotions and mental associations. The starting point in using this as a coaching technique is to select a play which has some echoes relevant to the client’s real life issues. You may wish to ask them to identify their own play, or to suggest one, with which they will be familiar.

- Using the metaphor of a play, the coach helps the coachee take the perspective of each of the principal actors, including him or herself.

- The coachee is asked to take the perspective of the audience and finally that of the playwright.

- Each iteration provides an opportunity to open up new and different options.

Free writing

This technique is useful in helping coachees become more self-aware and to take a more creative approach to difficult issues or decisions, once they have articulated their issue within the coaching session or before they come to the session, as part of their preparation.

The ground rules are simple:

- In conjunction with face-to-face coaching, encourage the client to do some ‘free writing’ to really solidify the ideas and thoughts that have been floating around during the coaching session.

- If they are stuck and have nothing to write, then provide some prompts. For example: ‘Things that I forgot to say to my coach during our last coaching session were… (finish that sentence).

- They should write as fast as they can in a limited time period (for example five to seven minutes).

- They should not worry about grammar, writing style or language.

- Then, you could ask the coachee to circle three words that particularly stand out for them. Don’t get into any discussion around their narrative. Repeat the process twice, using the three words generated in one narrative as the starting point for the next.

- Finally, ask them to spend another period writing in a more considered way about what they extract from these three narratives. This can be in prose or, if they feel creative, as a short poem or haiku.

My story

One of the central tasks of coaching is to help people bring their lives into focus. Sometimes this focus is directed at the whole of the coachee’s life; on other occasions it is more narrowly directed at their career.

- Over a week or two the coachee is encouraged to write ‘My Story – past, present and future’. It must have:

- A plot.

- Several sub-plots.

- A backcloth (the environment, place and society where the story unfolds.

- A moral (or several).

- Choices and dilemmas.

- Drama – deep disappointments and triumphs.

- A sense of continuity – grand themes that are echoed as the story unfolds.

- The coach then helps the coachee recognise and explore plots, moral and grand themes so that they develop deeper understanding.

Using fictional stories

- Consider an issue that you are facing.

- Think of a fictional story that has parallels with and can be used to explore the issue. Consider this story and speak out loud your thoughts and the story to your coach.

- Decide which is an effective method of dealing with the issue.

Note: The coachee must choose their own tale. However, there are some circumstances under which a tale or a character can be offered by the coach – these are situations where the it helps invite dialogue and exploration and are useful as exploratory comments on the dynamics of a situation rather than for labelling.

Creating new stories – starting from somewhere else

History creates a lot of baggage that suppresses creativity, leaving us unable to think why things cannot be done differently. When, where and why is this useful?

- Help the client create a story about their issue.

- Ask them to retell the story, starting from a different point or perspective. ‘If you were in this story, starting from somewhere else, what would you do differently?’

- Once these differences are listed, think creatively about how these approaches might be adapted to overcome some of the constraints they are subject to in your world.

Focusing on the senses

Employing different and unfamiliar sensations can also be helpful in tapping into intuitive, creative thinking.

Ask your coachee to:

- Set out a board and some clay; a plastic apron can also be useful, as this can get messy.

- Engage in a relaxation technique, going back to a memory of a place where they felt creative (often back to childhood).

- Put on the blindfold and play with the clay for 10 minutes without a fixed idea of what you want to create. Remember that they are researching and experimenting and not trying to create beautiful things.

- After 10 minutes, take the blindfold off and write about your experience with your non-dominant hand.

- After five minutes, or when you are finished, share your results with your coach for discussion.

Alternatively, ask your coachee to:

- Use air-dried clay to create three-dimensional shapes as metaphors for a situation.

- Allow the shapes to dry to become visual reminders to move on in the future OR destroy the shapes as a reminder that you need to let go.

Mask making

In a similar way, mask making can provide intuitive insights into complex issues. Although we may strive to be authentic, our public persona (the mask we present to others and sometimes also to ourselves) is rarely fully aligned with who we are or who we aspire to be.

Ask your coachee to:

- Create a mask with colour and detail of a situation or issue you are confronted with.

- Amend the mask, or create a second mask to signify the changes you want to make to yourself or the situation.

Circles of empowerment

This technique comes from our work on diversity, but has much wider application, especially in the context of recognising and overcoming self-limiting beliefs. It provides a visual representation of the factors that may drive or hinder us in achieving aspirations.

Ask your coachee to:

- Identify as many aspects of their personality and background as possible.

- Locate them against a line that represents the border between being a positive and negative factor in the specific context under examination.

- Circles entirely below the line indicate a severe hindering factor; those entirely above the line are enabling of the contextual goal. Those straddling the line have both positive and negative elements.

- Having identified each of these elements, the coach helps the coachee define what they can do to:

- Make more of the positives.

- Reduce the impact of negatives.

- Manage the line-straddling issues more effectively.

- An optional intermediate is to discuss how large each circle should be. The bigger the diameter, the greater its impact on the goal and the higher priority it should acquire in the dialogue between the coach and coachee.

Stepping out/stepping in

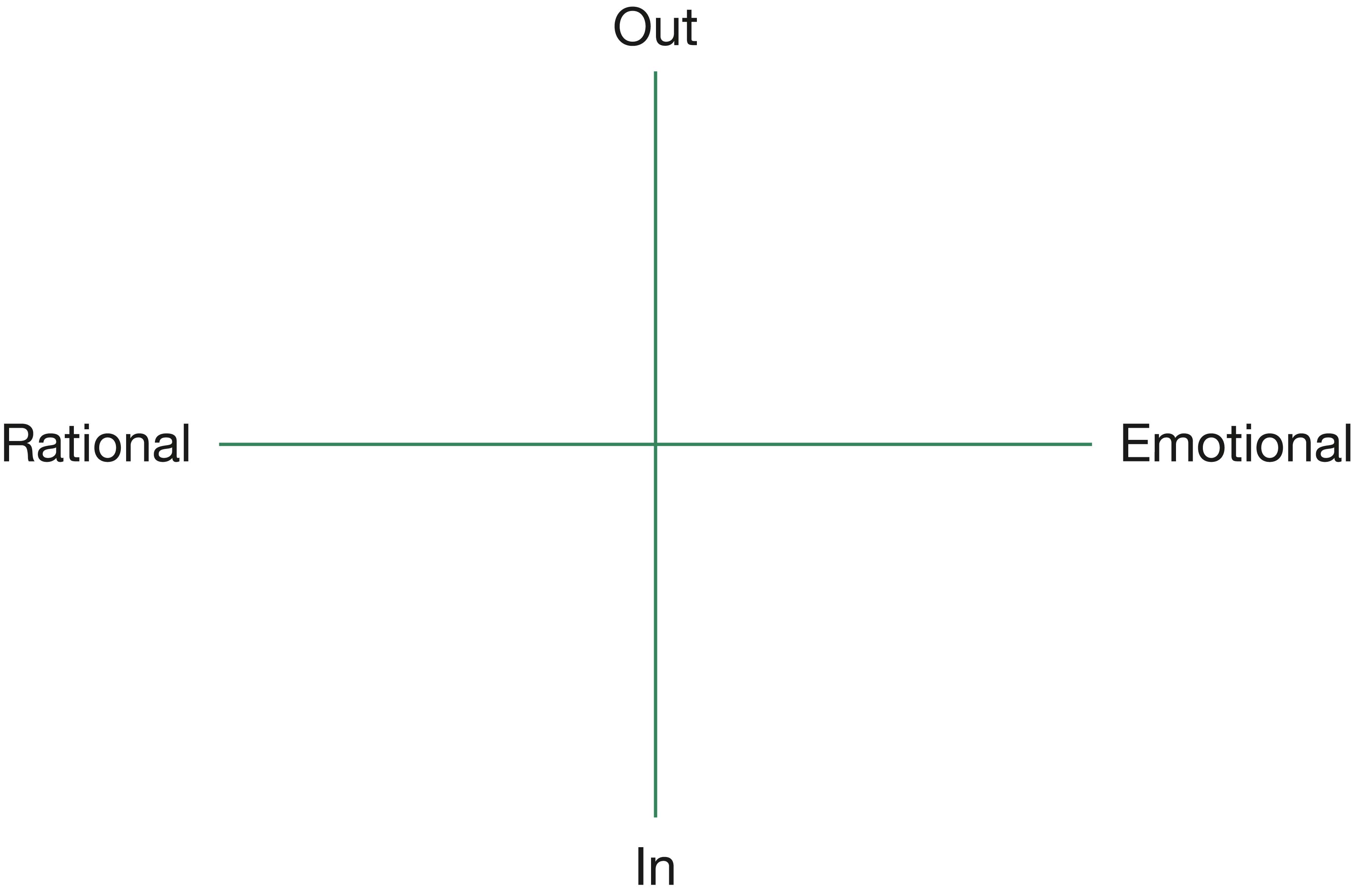

This technique arises from our observations of hundreds of coaches. We noticed that the most effective coaches frequently shifted the perspective of their questions as illustrated in Figure 5.1.

Stepping into the box is about acknowledging the individual’s own perspectives, joining them to try to understand what they are thinking and feeling, and why. Some people may come at an issue from a purely rational viewpoint, not wanting to explore their emotions for fear of what they might discover about themselves. Others may simply be too caught up in the emotion of a situation to think about it rationally.

Stepping out of the box is about helping them to distance themselves from the issue, either to examine it intellectually from other people’s or broader perspectives; or to help them empathise with and understand the feelings of other protagonists in the situation under discussion.

To truly understand and deal with an issue, it is frequently necessary to explore it from each of these perspectives. A small insight into one perspective can generate progress in another and a skilled coach uses frequent shifts of questioning perspective to generate these incremental advances.

Download Figure

Retro-engineered learning

The newcomer to a team is often at a severe disadvantage. Many of the tacit rules and assumptions, by which the team operates, are unconscious and far from obvious. Although some organisations make it easier by encouraging newcomers to question and challenge accepted practice ('Why on earth do we do it like that?!'), the reality in many cases is that newcomers are expected to learn the ropes rather than undo the rigging. Being too confrontational about the way things are done can be seen as threatening by established colleagues and as questioning their competence.

Retro-engineered learning is a relatively unthreatening way of giving the newcomer access to the evolution of culture and working practice. The process begins with the coach facilitating a conversation between the newcomers and one or more people, who have been in the team since its inception, or for a long time. The old hands are asked to explain briefly what the intention was in setting up the team and the initial expectations of it. The newcomers are then invited to say how they would have met this challenge. Then the old hands explain what actually happened and why. The focus then returns to the newcomers to say what they would have done next – what priorities they would have set, how they would have structured the task and so on – before the old hands share again what actually happened. By going to and fro in this way, the newcomers gain a sense of the team’s history and how it developed norms of thinking and behaving.

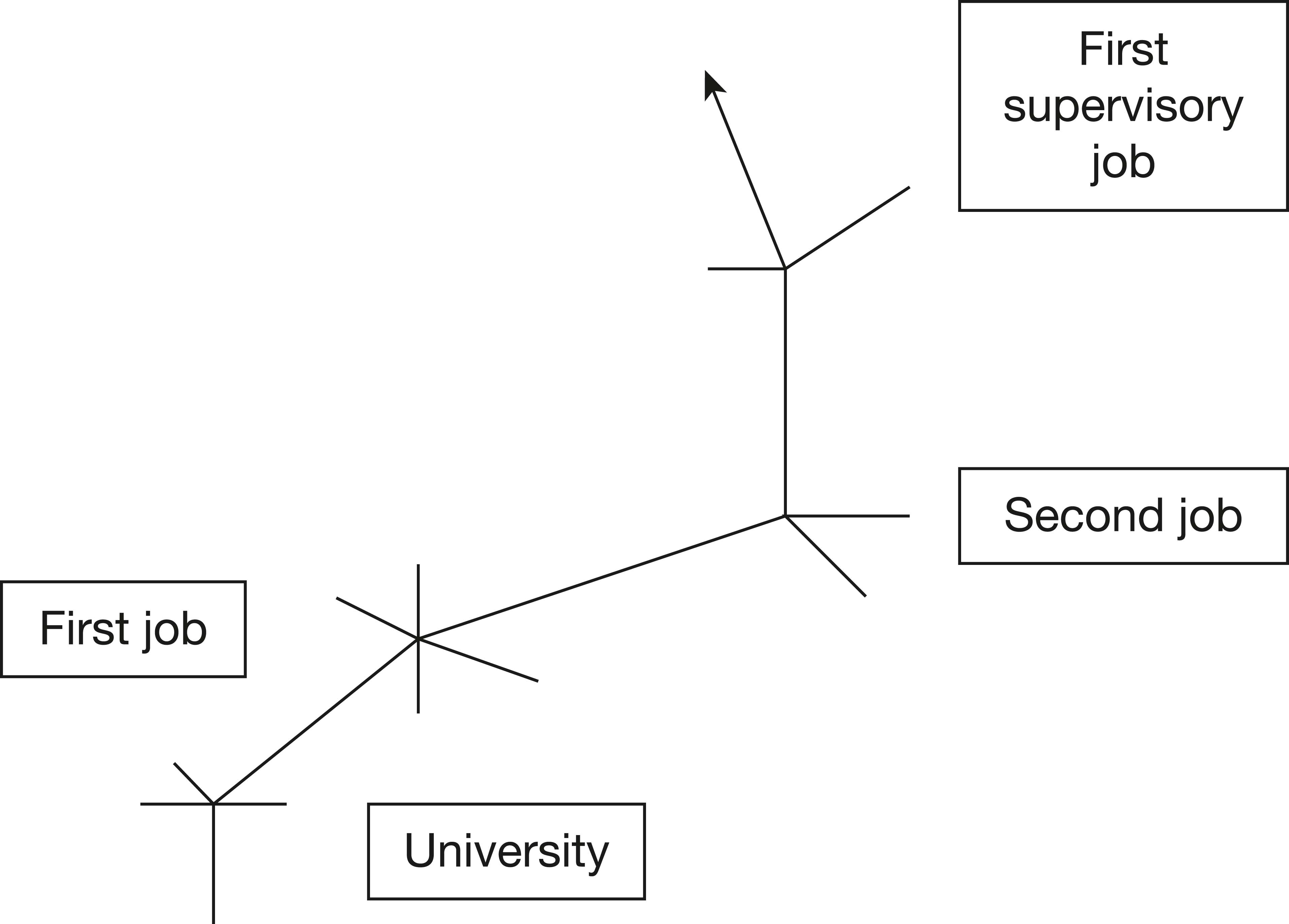

Career pathing

For many people, their career is something that happens to them, rather than something they have planned and managed. A healthy approach to career self-management can be described as one where there is sufficient proactivity to have a sense of purpose and direction, but a high degree of openness to unexpected opportunities. Career pathing involves helping the client reflect upon and learn from how they prepared for and managed past career choices and transitions; and develop appropriate strategies for their future careers.

The key steps are:

- Encourage the coachee, on a large piece of paper, to write down an early career choice – for example, which degree course to take at university.

- Take the coachee through a series of decision points, producing a map that looks something like the figure above.

- Help the coachee analyse each of the pivotal points in his or her career, drawing out lessons concerning the nature and management of the process.

- Projecting this into the future involves questions such as:

- What pivotal decision points are likely to come in the next 24 months or so?

- To what extent have you prepared for these?

- Who will you want to consult and when?

- Will these expand or reduce your range of options?

- What values will you want to apply to the decision?

- How are you going to make sure you exert control over this next step in your career direction?

Future talk

Future talk is a form of visualisation that is helpful in coaching. It allows coachees to identify small, observable, achievable tasks that would bring about change in a difficulty they are facing, whether it is a small difficulty, e.g. they feel left out of a group, or a bigger problem such as they don't have enough confidence to engage in an activity, or they may lack support at a meeting where they will be asked to address inappropriate behaviour.

It encourages all to hear a point of view that they may not have heard before and, because it does not involve 'blaming', it allows others involved to hear their part in the change process.

- Using ‘visualisation’, identify a small, observable, achievable task that would bring about change in a difficulty you were facing.

- Ask questions such as the following to see how you expect it to pan out in the future:

- What’s happening differently now that you are doing OK?

- How do you control things?

- How do you cope now when you feel frustrated- what do you do?

- If I saw you the day after things started changing, what would I have noticed that was different?

- What would others be doing differently?

- How are people different with you – what are they saying/doing differently?

Once you have established what they understand as needing to be done differently, set an observation task. For example, 'because you said that doing this would make a difference to your behaviour, I would like you to observe what difference it makes in the next week’.

Visualisation – expand and contract

Visualisation can help us slow down and focus on a particular issue.

- Start by closing your eyes and feeling the pressure of your feet on the floor and your back on the chair.

- Become aware of other touch sensations, such as the feel of your spectacles or your watch.

- Listen to your breathing and maybe your heartbeat. Become aware of the smells around you.

- Open your eyes and focus on a spot immediately ahead and above you.

- Without moving your head, increase your awareness of what you can see to the sides – your peripheral vision – but do not be distracted by things you hadn’t observed before. Do the same for other points in the room.

- Enjoy the quiet for a while.

- Now close your eyes and visualise the issue or situation. Make sure to exaggerate of minimise key elements, for example, ‘Instead of charging £1 an hour to Mark what would happen if we charged £10’.

- When these alternative scenarios have been explored, open your eyes and discuss any insights that have arisen.

Helping people articulate complex problems

If we are in too much of a hurry to help a client find a solution, it’s easy to oversimplify the issue they present. In practice, a presented issue may be a small part of a larger issue, or composed of several distinct but overlapping issues. Giving the client space to talk through and expand their understanding of an issue, before focusing down, helps us address it at the right level.

As a coach, you can:

- Encourage coachees to start somewhere, and then meander in whatever direction makes sense to them:

- Where and how they meander is information in itself.

- It is quicker to get something out, however confused, which you can subsequently work on, than force them to try to be very logical about it (a move which may also undermine rapport, since they may read it as critical of them).

- Once there is a ‘draft version’, you can use any or all of the following to help your coachees see connections and understand the ramifications:

- Spider diagrams or mind maps can be very useful in teasing out connections in a complex situation or issue.

- Other forms of drawing, for example,

- Time lines – use a horizontal axis as development over time. A refinement here is to draw a horizontal life, and invite the coachee to place positive aspects of the situation above the life, and negative ones below it, moving through time from left to right.

- Archery target – put the coachee in the bull’s eye, and then place other people closer or further away (using concentric circles as demarcations). Describe who they are, and what their part in the situation is.

Refinement: have a ‘pie slice’ of the circle (or even a semi-circle) represent a particular salient group – e.g. enemies. This technique is particularly useful where you have a ‘cast of thousands’.

- Story perspectives: ask the coachee to run through the story several times, as seen from different people’s perspectives (e.g. themselves, their boss, an outsider).

- Ask for a ‘headline’ describing the nub of the issue. Then ask for examples of the headline from the situation.

- Invite the coachee to liken the situation to several different analogies (‘it’s like a bear pit in there’; ‘it’s like living in a Force 10 gale’; ‘it’s like nuclear winter’). Then ask them how (a) it is like each analogy; and (b) how it is unlike each analogy.

- Introduce them to the distinction between the ‘truth of the physical world’, and the ‘truth of human being’. In the former, something cannot be both something and its opposite at the same time. So a crow cannot be both black and not black. On the other hand, social truth can and does encompass paradox. Something can be frightening and enjoyable at the same time. A person can be both helpful and unhelpful at the same time. In other words, legitimise (apparent) contradictions as reasonable and, quite possibly, true. This will give a much richer picture of their perceptions when they don’t feel that they have to iron them into a logically coherent narrative.

Drawing

Drawing helps people access creative circuits they may not normally employ – using stick figures, and speech bubbles like a cartoon may assist in enhancing an atmosphere of experimentation and exploration.

- Ask the coachee to draw a picture to describe the situation they are in now.

- Support them as they extract meaning from what they have drawn.

- Ask what or who is not in the picture – and what can be inferred from that.

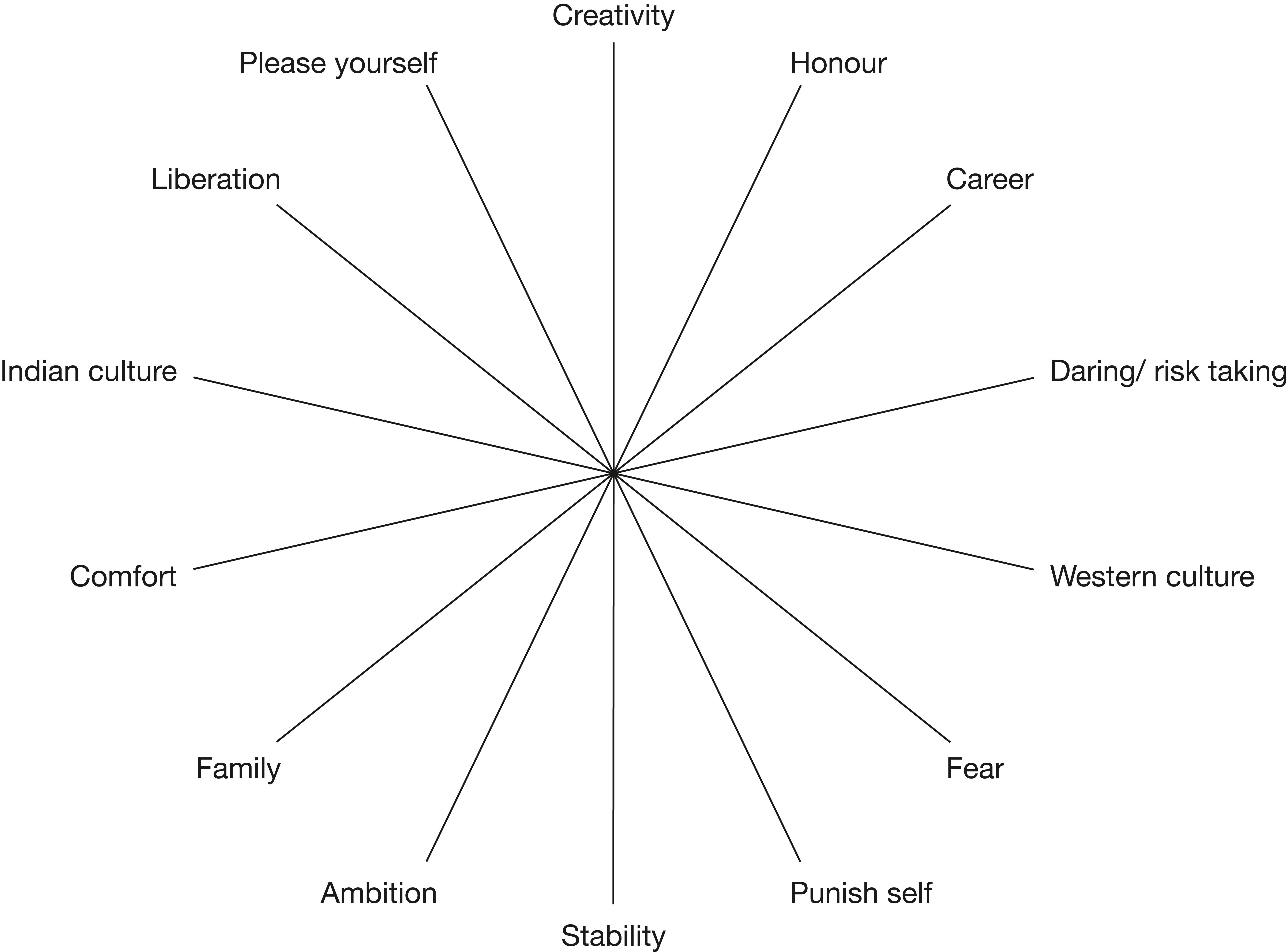

Issues mapping

This technique aims to capture, very quickly, in an initial coaching conversation, the dominant themes and issues in a client’s life.

As a coach, you can:

- Ask the coachee to tell the story of ‘How I became me’. Listen for recurring themes, for contradictions, for opposites, for patterns of almost any kind. Each time the coach identifies a theme, he draws it as a line (see Figure 5.3). At each end of the line, the coach identifies a pair of competing demands upon the coachee.

- The emerging issues are then the topics for the next coaching session.

Appreciative Inquiry

As the name suggests, Appreciative Inquiry explores issues from a positive perspective.

The start of the AI process is the Affirmative Topic Choice. The first question tends to be something like, ‘What do you want to learn about and achieve?’ This is followed by questions checking whether the first response is all that is wanted, until the respondent gets to the point of being emphatically clear about what they really want. This gives a focus for the appreciative interview, which follows. The interview is about discovering information based on questions such as:

- What gives life to your being in the organisation?

- What is the best there is here?

- What do you most appreciate about your work here?

- Could this be the basis for our coaching conversations?

- Can we see life in the organisation not as a problem to be analysed, planned for and solved, but rather as an appreciation and valuing of what is best, an envisioning of what might be and a dialogue with others affected about what should be? (This approach conceives life in the organisation as a mystery to be embraced.)

The aim is to find the ‘positive change core’ – the essence of every strength, innovation, achievement, imaginative story, hope, positive tradition, passion and dream that the individual has, engaged in the pursuit of the Affirmative Topic.

The four-stage AI process (the 4Ds) is:

- Discovery: Mobilise a systemic inquiry into the positive change core.

- Dream: Envision the individual’s greatest potential for positive influence and impact on the world.

- Design: Craft a way of going on in which the positive change core is boldly alive in all strategies, processes, systems, decisions and collaborations.

- Destiny: Invite action inspired by the discovery, dream and design.

This represents a process for developing a coaching relationship over time.